Our culture has an odd identity crisis. It is not that we do not know who we are, but that we are apparently incapable of shutting up about it. From identity politics to the elevation of gender identity over biological sex, our culture is replete with conflicts rooted in assertions of identity. Arguments routinely commence with statements of identity.

But do we protest too much? Do persistent proclamations of identity cover a brittleness underlying our identity obsessions?

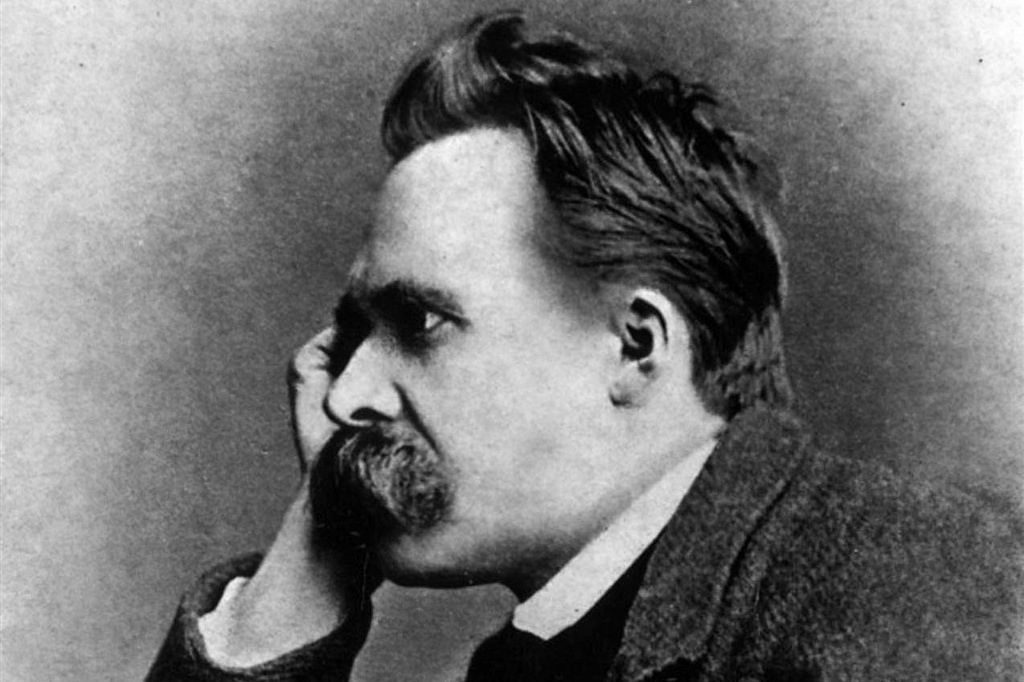

As a straight white cisgender Christian man, I suggest that an explanation for this identity crisis may be found in Nietzsche’s famous, often misunderstood claim that God is dead. The death of God led to a detachment of identity and meaning from anything permanent, which has left people trying to construct their own identities from the contingencies of human existence.

The Death of God

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.The death of God is more than disbelief in God or the flat statement that God does not exist. From his first declaration of the death of God (in a story about a madman who initially seeks God only to announce his death), Nietzsche described a psychological and cultural event rather than a triumphant philosophical postulate. The madman in Nietzsche’s parable announces the death of God to “many people standing about who did not believe in God.” Indeed, they had mocked him for his initial insane search for God. He is no obnoxious apostle of unbelief, come to tell believers how stupid they are.

Rather, he is a seeker after God who realizes the implications of the unbelief surrounding him, which he comes to share. Those who first disbelieved remain oblivious to the death of God, even though they have themselves killed Him. The madman concludes that he has come too early: “Lightning and thunder need time, the light of the stars needs time, deeds need time, even after they are done, to be seen and heard. This deed is as yet further from them than the furthest star.—and yet they have done it!” Because the death of God is not mere unbelief but a result of it, those who killed God were unaware of what they have done. They still lived with many of the comfortable moral pieties derived from established Christianity, even though they no longer believed in the source.

But the eventual result of their unbelief is the destruction of the human conception of the world and its source. The madman who announces the death of God expresses wonder and despair at the deed: “How were we able to drink up the sea? Who gave us the sponge to wipe away the whole horizon?” God, as an idea, not an entity, had provided humanity with meaning and coherence, and established the world as a home for mankind. The death of God was the death of the Beyond as a wellspring of meaning and order in life. God, or some sort of transcendence, had been considered the source of love, awe, greatness, order, truth, beauty, and everything else that seemed to draw humans beyond themselves. All of this was now revealed as mere human invention—an elaborate game of make-believe.

Thus, the death of God had unmoored the world from what had been its source. As the madman put it,

What did we do when we loosed this earth from its sun? Whither does it now move? Away from all suns? Do we not dash on unceasingly? Backwards, sideways, forwards, in all directions? Is there still an above and below? Do we not stray, as through infinite nothingness? Does not empty space breathe upon us?

The divine sources of transcendent identity and meaning were gone, along with the murdered God. The cosmos had been shattered; creation was no longer created. There is no higher meaning to life, the universe, and everything. Mankind no longer had a given place within the universe, but was merely a minuscule, purposeless development within it.

The Challenge of Nihilism

Facing this stark vision of reality without despair is the challenge of nihilism, which Nietzsche sought to overcome in his greatest work, Thus Spoke Zarathustra. The divine source of value and meaning was revealed as a human delusion. If mankind was not to succumb to nihilism, it would need to embrace the conscious creation of new sources of meaning and new identities for itself. Humans would have to embrace existence and knowingly self-create. And we would have to do this despite our contingency, finitude, suffering, and banality—the last being perhaps the most distressing to Nietzsche.

This is behind the idea of the Übermensch, the superior, self-overcoming man who can create new meaning and values. As the madman cried out,

God is dead! God remains dead! And we have killed him! How shall we console ourselves, the most murderous of all murderers? . . . Is not the magnitude of this deed too great for us? Shall we not ourselves have to become Gods, merely to seem worthy of it?

But what if we cannot? Are we left waiting for the overman?

There is little evidence thus far that we have filled the void left by the death of God, though we have tried. In fact, Nietzsche’s diagnosis and prescription explain our culture’s odd identity crisis. Our endless discussions of identity as something to construct and deconstruct are rooted in the cultural unfolding of the death of God.

This analysis explains both the popularity and the precariousness of group identities. Responding to a crisis of identity by reverting to tribalism is natural (which is why we see even well-off, successful students and professionals doing so), but tribal identities have lost their place in the cosmos. They are no longer tied to cosmic or transcendent order—they are known to be contingent. Consequently, tribal identity is no longer a secure psychological retreat into a stable source of meaning but a contested construct. Getting “woke” and engaging in identity politics are attempts to find meaning in something that is an acknowledged social construct.

Those living after the death of God struggle to claim identities that are more than social constructs or personal idiosyncrasies. We must self-create, and yet we doubt our ability to do so authentically—with good reason, given that the materials we must use are contingent cultural artifacts. What is our own that we can claim at the core of our identity?

Being, Feeling, and Desiring

Our culture tends to respond to the question “Who am I?” by asking “Who do you feel like?” and “What do you want?” Desire, especially sexual desire, is at least something that seems authentically our own. We identify with our consumption, sexual consumption perhaps most of all. And even in our de-divinized time, eros retains a hint of divine madness. But the death of God has made materialists of us. The question has transformed from “Who do you love?” to “How would you like to have sex?” The question is not about persons understood as integrated wholes, but about what sort of stimuli your body reacts to. Thus, for many people, what were once considered private perversions have become the centerpieces of their public identities.

This is behind the increasingly common claim that to challenge people’s sexual behavior or gender identity is to question, deny, or attack their humanity and even their existence. This seems insane to those who still reside in a Christian cosmos, for whom sexual desire or one’s feelings about gender are not at the core of one’s identity, and for whom criticizing sinful acts is a far cry from enacting a genocide of the sinful. But to those whose experiential sense of self is only that which they have created or adopted from their culture and their own desires, this makes sense. If self-creation is the fullest expression of our humanity, then critiquing someone’s self-constructed identity is to critique his humanity.

It often seems that the opposing sides of our cultural and political conflicts are living in different worlds. They are. Those who believe they are living in a created cosmos really do inhabit a different psychological world from those living after the death of God. Those whose identity is rooted in the divine order of existence are divided from those whose identity is self-created.

However, the lines are not always clear. Just as the audience in Nietzsche’s parable was unaware of the death of God despite its unbelief, there are many today who are unconsciously divided between the two worlds. Facing the full implications of the death of God takes courage and perspicacity that few have, even after Nietzsche has led the way. Instead, people often live within a mixture of self-creation, nihilistic despair, and residual religiosity mostly derived from Christianity—self-creation when it flatters and indulges, mixed with sentimental religiosity for comfort. All the while, however, the black snake of nihilism chokes us; we are unable to live authentically spiritual lives and unable to replace the murdered God ourselves.

Inconsistent and unstable identities prevent us from living with authenticity and integrity, especially in relation to others. Harmony is impossible when our identities are unstable and grounded only in contingency and desire. Conflicting identity claims by groups and individuals compete with no prospect of resolution, for they believe that there is no source of identity beyond the human—the all too human.