Tourists, reenactors, and history enthusiasts annually converge at Gettysburg for the first three days of July to honor the historic 1863 battle. But as with so many other events, the Covid-19 pandemic has either altered or canceled those plans in 2020. Across the nation, protests connected to the violent deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor have also sparked another form of unrest for an already anxious country. Current discussions surrounding race and social justice have once again drawn the nation’s attention to the stain of slavery, the history of the Civil War, and many other peripheral issues, such as monuments and war memory.

Historically, the hallowed ground of Gettysburg has offered important lessons of the past, present, and future to many generations of Americans. I recently interviewed Dr. Allen Guelzo to explore this enduring legacy.

Howard Muncy: I would like to begin with your thoughts on how Gettysburg emerged as an important American symbol in the immediate aftermath of the battle. In your book Gettysburg: The Last Invasion, you claimed that contemporary Americans realized they had just experienced “something worth dying to protect, something worth communicating to the living.”

Dr. Allen Guelzo: People understood the significance of the Battle of Gettysburg almost before it was finished. In fact, the third day of the battle had not yet reached its completion when the first tourists to the battlefield showed up. So even while the shooting was still in progress, people were already making a pilgrimage to the battlefield. That sounds to us not only risky, but incredible. And yet, people did perceive that this was an important conflict. It was seen that way for several reasons. One, this was Robert E. Lee’s great gambit to invade the North. And by invading the North, what he hoped to do was at the very most, encounter the federal Army of the Potomac and inflict a defeat on it. But at the very least, he wanted to move into Pennsylvania and demonstrate the weakness and inability of the Lincoln administration to protect its own territory.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Either way, by inflicting a defeat on a federal army or simply by occupying Northern territory with impunity, Lee believed that the political damage would be so great as to cripple the Lincoln administration, force it to the negotiating table, and bring an end to the war. And virtually everybody believed that once negotiations with the Confederacy began, there was really no likelihood of going back to hostilities. It would have amounted to a recognition of the Confederacy’s independence.

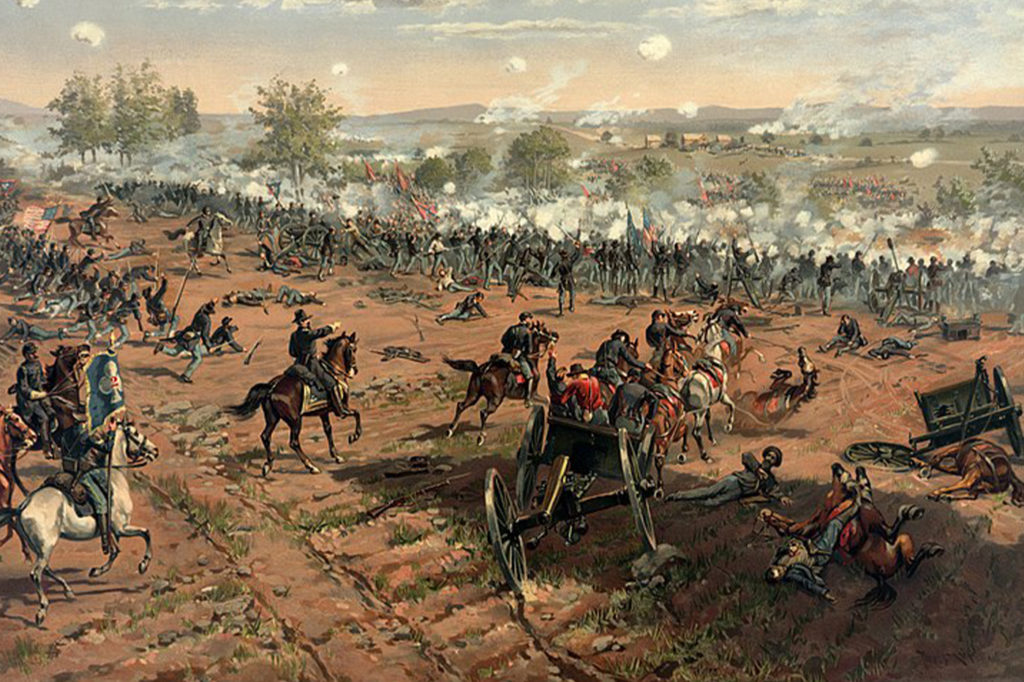

Another factor was the sheer size of the battle. Gettysburg was an epic struggle over three days and involved hundreds of thousands of men on each side. The totals were staggering, with around 50,000 casualties over the course of the three-day battle. At the upper end of the estimate, historians believe approximately 9,000 soldiers from both armies were killed outright. Those numbers made immediate headlines. What was significant as the weeks went by was not only that this battle had been a tremendous affair, but that Lee had suffered, and the Confederacy with him, a serious repulse. After three days of fighting Lee was forced to withdraw, and his army could have easily been surrounded and captured. That would have been an end to the war in a very different direction. But as it turned out, Lee crossed the Potomac and escaped back into Virginia, much to Lincoln’s intense and furious disappointment. Nevertheless, the battle itself was an important victory for the federal Army of the Potomac, which had up to that point sustained numerous defeats. Gettysburg repulsed Lee and his overall plan to affect Northern public opinion.

Gettysburg was an epic struggle over three days and involved hundreds of thousands of men on each side. The totals were staggering, with around 50,000 casualties over the course of the three-day battle.

Above all, reports from Gettysburg came to President Lincoln on the same weekend as did the news from the West about the fall of the Confederate citadel at Vicksburg on the Mississippi River. The fact that the news of these two victories came on a Fourth of July weekend seemed immensely, almost providentially, symbolic to Lincoln. At an impromptu gathering at the White House of well-wishers, Lincoln spoke on that particular Fourth of July weekend about how, just over eighty years before, the United States had been formed around the proposition that all men had been created equal. Now, on that very same anniversary, had come two tremendous victories. These victories appeared almost as a ratification of the Declaration of Independence and its principles. Lincoln took them as a symbol. And when he comes at the invitation of David Wills of Gettysburg to speak of the dedication of the cemetery, it moves him to talk not just about the cemetery, not just about dedication, but about the entire reason that the war is being fought.

HM: You have stated that the November 1863 dedication at Gettysburg bordered on something of “a national revival.” Much of this idea is couched in Lincoln’s bold concept of a new birth of freedom. Americans often associate years like 1776, 1789, etc. as the most important on the American continuum. But where would you rank 1863 in terms of significance?

Guelzo: 1863 is the date when we passed our final exam. Lincoln said in his Gettysburg address that fourscore and seven years ago the fathers had created this Republic “conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” Lincoln then switched to the present 1863, we are involved now in this great Civil War and we’re met on a battlefield of that Civil War. But what had happened in 1863? Lincoln continued: We are testing whether this nation “or any nation so conceived and so dedicated can long endure.”

Lincoln once made the comment that popular governments, governments that rest sovereignty in the people, like the American Republic, must undergo three tests. The first test is the creation of the government itself. The second test is getting it up and operating. And the third test comes when it must resist attack from insurgencies within. Lincoln had believed—and this runs all the way back to his first great speech in 1838 on what he called “The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions”—that the American Republic could likely never be overthrown by outside attack. Lincoln said if there is going to be an end to the American Republic, we are probably going to be responsible for it ourselves, and it will come from within. This thinking informed those three tests that he thought a Republic had to pass.

Lincoln believed that the American Republic could likely never be overthrown by outside attack. Lincoln said if there is going to be an end to the American Republic, we are probably going to be responsible for it ourselves, and it will come from within.

The American Civil War was exactly what he described as that third test. Can we survive an attempt from within to destroy the American Republic? Lincoln believed that what had happened at Gettysburg and what was happening in the Civil War was the third test. If we dedicated ourselves to the principles of the Republic with the same fervor that those soldiers had dedicated themselves—even to the point of “the last full measure of devotion”—then we would indeed experience a new birth of freedom. It resembled a revival meeting at which the term “new birth,” since the days of the eighteenth century, meant a renewal of spiritual vigor. If we could dedicate ourselves that way, we would experience exactly that new birth, and America would pass that final exam that a Republic must pass. That is what he exhorted people to in the closing sentences of the Gettysburg Address. If that happened, Americans would not only experience that new birth, but it would ensure that government of the people, by the people, for the people would not perish from the earth.

It was significant in its own way that Lincoln even chose to go to Gettysburg on November 19th, 1863. Lincoln did not often stray outside of Washington, D.C. during the war. He turned down numerous invitations to speak at various places around the North. The only times he did leave his post in the Executive Mansion were to go south into Virginia to visit the armies, to review troops, and to consult with his generals. Otherwise Lincoln, who was something of a workaholic, tended not to stray very far from Washington. Accepting the invitation to come to Gettysburg was itself significant. Simply by the fact of his going there, he gave evidence of the importance he attached to Gettysburg.

HM: On my first visit to Gettysburg, a monument that really caught my attention was the Eternal Light Peace Memorial. The large monument, composed of Maine granite and Alabama limestone, was dedicated in 1938 during another calamity—the Great Depression. It seemed to suggest efforts toward a national healing. What lessons of reconciliation do you think Gettysburg holds?

Guelzo: That is a difficult question and one that people have wrestled with from 1863 onwards. Not very long after the battle, people were already hoping to use Gettysburg as a platform for promoting reconciliation between North and South. As early as 1869, a promoter in Gettysburg wanted to arrange for all the senior officers who had been involved in the battle, North and South, to come to the Gettysburg battlefield to point out what they considered to be the significant moments of the battle. And they would do it together. George Meade for the Union Army and Robert E. Lee for the Confederate Army were invited. It did not quite work out, because Lee declined and would not come. His response was that reconciliation would be better achieved by simply burying the memory of the past.

In the 1880s, groups of veterans from both Union and Confederate armies came to Gettysburg and were supposed to have reunions of the Blue and Gray there. Almost invariably, these reunions broke down in quarrels between the old veterans. In many cases, Union veterans refused to countenance the notion that their Confederate counterparts would be allowed to parade through the town displaying Confederate flags. They had fought against those flags, and the flags represented treason to them. They were not going to participate in that. So, while from time to time well-intentioned people were able to stage photographs of Confederate and Union veterans shaking hands over the wall at The Angle on the Gettysburg Battlefield, what surrounded those photographs was a good deal less pleasant and sometimes not entirely printable.

This persisted straight up until 1913, when a tremendous jamboree was planned at Gettysburg that would bring Union and Confederate veterans of the Civil War together on the fiftieth anniversary of the battle for a great display of reconciliation. Even there, matters broke down because the Union veterans insisted on no display of Confederate flags. President Woodrow Wilson, a Southerner, was invited to address the gathering. Wilson took the train into Gettysburg, made his brief speech, got on the train and left. But when he came to make his speech, Confederate veterans who had concealed Confederate flags all burst out with these flags to wave them at the president because Wilson was from the South. This created tremendous consternation among the Union veterans who refused to applaud Wilson’s speech. So even in 1913 there was still great disagreement.

The last of these reunions occurs in 1938. And, once again, the effort was made to promote reconciliation. By this time, the number of veterans who survived to attend were very few. Most of them were very old, and there was not much concern of trouble to break out. But the real irony of the Eternal Peace Monument is that it is dedicated there in the summer of 1938. What happens in the Fall of 1938? The Munich crisis. So here, a monument that was supposed to testify to eternal peace finds that peace is very short-lived. And the irony of that monument is that a peace monument turned out only to be a presage of a great World War that would very shortly engulf the entire planet.

HM: As a young student, I first developed a fascination with Gettysburg after reading Michael Shaara’s The Killer Angels. Soon after, I watched the Ken Burns series on the Civil War and eventually started picking up academic books and studying the entire subject. The novel served as one of the main entry points to what developed into a larger love of history. Over the years, I have used excerpts from the book in my own classroom. Today, some may consider The Killer Angels to be inappropriate or even offensive for educational use. In the current political and social climate where symbols, literature, entertainment, and even history are under critical evaluation, do you think these debates pose a greater potential for healing or for harm?

Guelzo: I think they pose a tremendous threat of harm, because what they do is to use historical relics, documents, personalities, and records as stalking horses for modern political energies. When we do that, we pervert the study of the history into a pursuit of our own personal fantasies. And this is not a new problem. If anything, this has been one of the difficulties that historical writing has always struggled against: to prevent political agendas from prostituting history into mere agencies for politics. The immediate impact of this causes people to polarize their versions of history and hurl them at each other like brickbats. The long-term response is for people to treat history as radioactive and not to want to touch it at all. Partisanship, and the conversion of history into partisanship, rarely accomplishes anything more than giving in to the immediate moment, which in turn creates an opportunity for bad temper. The long-term difficulty is that it convinces people to stay away from the history.

But to lose our grip on our history is simply not an option. For Americans, our history is bound up with our identity. We do not identify ourselves by race, by religion, by ethnicity, by language, by culture. What identifies Americans is a historical moment in 1776 when we reached out and affirmed, as an issue of natural right and natural law, that all men are created equal and are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights. Among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. When we look for an American identity, it doesn’t come in flesh and blood and soil. It comes from ideas rooted in a history. When our history becomes, for whatever reason, something we are afraid to touch, something that becomes radioactive, then we cost ourselves a great deal of what our identity is. And that is a tremendous loss, because confusion ensues. And if we are confused as to what it means to be Americans, then we have lost the fundamental reason that we hold out this beacon of liberty to the world. And in a sense, what we have done is to recall the final exam that we passed in 1863 and to mark it down as failed. That is not a result that I am at all happy to see happen.

For Americans, our history is bound up with our identity. We do not identify ourselves by race, by religion, by ethnicity, by language, by culture. What identifies Americans is a historical moment in 1776 when we reached out and affirmed, as an issue of natural right and natural law, that all men are created equal and are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights.

HM: You have addressed radical changes in school curriculum such as “The 1619 Project” in some detail with a series of articles and recent interviews. Adoption of some of these changes would minimize or eliminate the deeper lessons of historical events such as Gettysburg. What advice would you have for concerned parents or young history teachers who feel pressured to accept or recast history?

Guelzo: In practical terms, I would advise parents and I would advise teachers to dwell on one word: controversial. There’s nothing that disturbs the peace and equanimity of municipalities, school boards, and other governing agencies more than the idea that they have just swallowed something that is “controversial.” And indeed The 1619 Project is controversial. It sets out, and announces itself, to be a controversy. If people understand that what they are being offered in The 1619 Project is something that is controversial, that immediately is going to make people uncomfortable about embracing it, as they should be.

In a larger sense, what I encourage both parents and teachers to do is to find historical alternatives. Because there are other books and resources. I would recommend, for example, Wilfred McClay’s new American history Land of Hope, which offers a gracefully written, remarkably thorough, but also inspiring, journey through the American epic. I think that a school could scarcely do better either through its parents, its teachers, or its school board, than to look seriously at adopting McClay’s book. I offer that only as one example. There are several other examples that could be proposed. A number of us are currently working on and creating curricula that I hope will be made available for public access over the next six to eight months. But there are alternatives in warding off the rush that is going to be experienced in some quarters to embrace The 1619 Project as though it was history, when it really is a gigantic form of conspiracy theory.

HM: Are there any other valuable lessons from Gettysburg that you think America could find inspiration or benefit from knowing?

Guelzo: One lesson that I dwell on a good deal is rooted in the experience of the second day’s fighting. On July 2nd, 1863, Robert E. Lee launched a gigantic flanking attack on the Army at the Potomac. It was a hammer blow that came within inches of success— a success that would have shattered the Army at the Potomac and compelled its abandonment of Gettysburg. It failed because, in large measure, numerous ordinary soldiers and the officers took matters in their own hands and saved the day. I think of individuals like Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain and his 20th Maine Regiment. They are probably the most famous of those who fought on the Union side at Gettysburg. But Chamberlain was one who on his own hook and by his own decisions facing the possibility of being overwhelmed by Confederate attack, ordered a counterattack with bayonets. What did he know about bayonets? He was a rhetoric professor from Bowdoin College who had no experience of military life. Yet he acted on the only impulses he knew, which turned out to be just exactly the right impulses. And the great thing is that Chamberlain, although he is probably the most celebrated that way because of The Killer Angels, was by no means alone.

Also on Little Round Top where Chamberlain and his regiment fought was Strong Vincent, the commander of the brigade to which Chamberlain belonged. There was Paddy O’Rorke and his 140th New York coming to the rescue at just the right moment. It cost O’Rorke his life, but his regiment threw back a Confederate attack that would have overwhelmed the other spur of Little Round Top. I go on from point to point to point, to the First Minnesota taking on an entire Confederate brigade in the center of the battlefield, to Samuel Sprigg Carroll and his three regiments sprinting across Cemetery Hill at just the right moment to repel a Confederate attack that could have overcome the federal position at its other flank. And this kept happening all through the late afternoon and early evening of July 2. Ordinary soldiers, line officers, on their own, without direction from the generals, somehow looking at situations, sizing them up, making the right decision and doing it on their own accord.

I think those are some of the most remarkable stories to emerge out of the Gettysburg battle. It displayed not only the courage of those individuals, but it displayed something about the American temperament itself. The ordinary American rises to the demand of situations, looks around, sums things up, makes the decision, lives with the consequences, and somehow miraculously does it right time and time and time again. That, to me, is one really great lesson to bring out of Gettysburg.