When I go to the beach, the odds are ten to one that I will be confronted with the same phenomenon once so memorably described by John Updike: “a sheet of brilliant sand printed with the runes of naked human bodies.” It is, after all, “beach body” season, and those who can muster up some better version of their own physicality usually do. Now, for those of us approaching middle age, this felt imperative presents more and more pressing challenges: over time, the collagen in one’s skin begins to fall behind (sometimes quite literally) in the struggle with gravity, and the much-vaunted beach body becomes harder to achieve. On the other hand, no matter our age, we cannot help being drawn to it, out of either appetite or rivalry. Here are the roots, laid bare every summer, of a thousand middle-aged pressures on marriage and family life.

Still, an obvious counterpoint is the fact that it is becoming easier each year to stay young longer, or at least to appear to do so. A few months back, The Wall Street Journal ran a spread: “The New Fifty,” featuring quinquagenarian celebrities such as Jennifer Lopez and Jennifer Aniston alongside images of their counterparts from the mid-century. The contrast was gasp-inducing: Vivian Leigh and Rita Hayworth looked like, well, middle-aged women in their fifties, while the fifty-year-old J-Lo would easily pass for half her age. But how many of us are capable of Lopez’s feat? Perhaps only the wealthiest, for it apparently requires regular surgeries, an array of strategic injections, a fastidiously curated diet, and daily exercise coaching. Fifty is in that sense only “new” for those in the topmost economic strata.

The gradual fall away from the beach body is a concern for both sexes. Certainly, men suffer as the flesh begins to droop, but the burden on women is undeniably greater. If the goal is to stay twenty as long as possible, those who heroically bear and feed the next generation with their own bodies will necessarily have a harder time keeping up. A mother’s body is just different, and, short of the legerdemain available to the wealthy, this difference cannot be undone. The gap between social expectation and reality can be deeply discouraging and wounding to women, even without external criticism or rejection. And how many marriages end in middle age, when the husband, no longer attracted to the woman who has borne his children, sidles off in pursuit of someone more capable of the youthful physical ideal? The examples are too numerous to mention, in every magazine, newspaper, family, and social milieu.

Today, the beach that features so many specimens of that fetching ideal is not found only on the sandy coast, but everywhere: online, in the computer on my desk, and in the device in your pocket. It was Melville who wrote that every human being has a sea within him. We might add that there is also a beach beside that sea: a place of unforgettable attraction, titillation, and danger. That beach brings with it all kinds of interrelated moral and social questions.

Start your day with Public Discourse

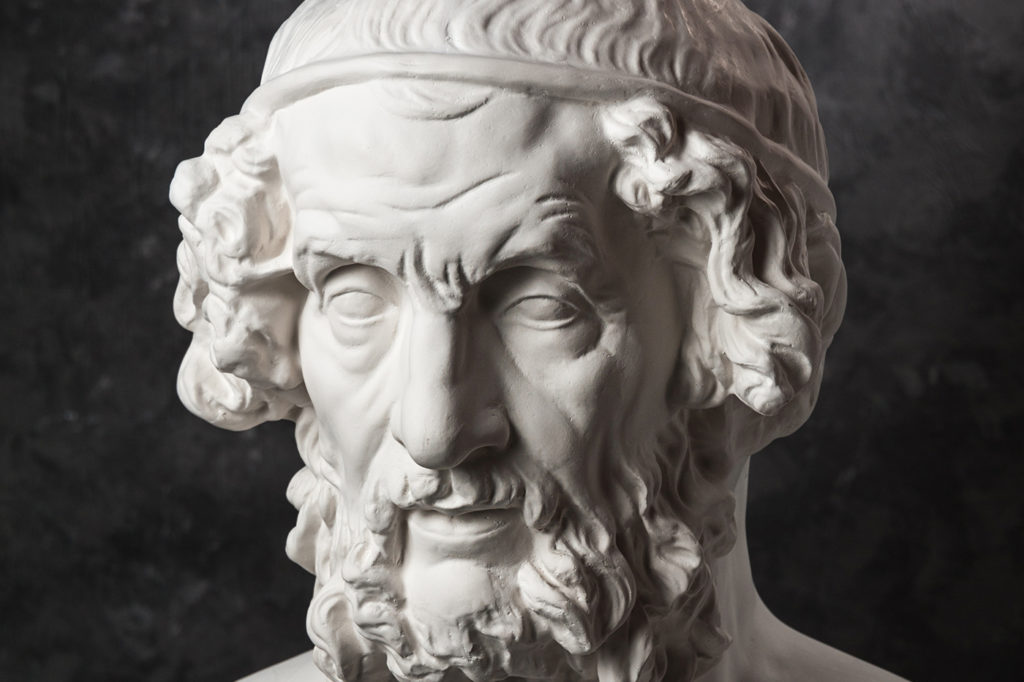

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Beachgoing with Homer

Thankfully, though, there is a deposit of beach wisdom for us to turn to in our hour of need. Homer’s Odyssey, as it happens, is very much concerned with the beach, both topographically and in the sense I have been describing. The Odyssey is of course about homecoming—nostos, in Homer’s Greek—in that Odysseus has been ten years at war in Troy and must now go home to Ithaca. But even more important is the moral, psychological dimension of his homecoming: he must return to the ways of peace necessary for human flourishing. That effectively means returning to a better, more essential version of himself.

Seen in this light, the many stops he makes along the way—the episode with the cyclops, or the lotus-eaters, or the shades in the underworld—stand out as encounters with places that are not Odysseus’s home. The druggy sopor of the lotus-eaters’ isle, for example, is attractive, both to Odysseus’s men and to humans in general: a state of forgetfulness that takes one beyond the worries and struggles of life. Yet, Homer implies, that state also dehumanizes its inhabitants by making them careless of community and purpose. That is not home. It is not where humans belong.

Homer enables us to see something similar in the episode on Calypso’s island, and it is here that we encounter both the allure and the problems of the beach. The situation is, from a certain point of view, ideal: after three years of luckless voyaging, completely bereft of all his original companions, Odysseus washes up on the shore of an island paradise. Not only are food and shelter taken care of, but Calypso, an immortal goddess, is also present to meet his sexual desires. Indeed, when the scene opens, Odysseus has been seven years with Calypso, and has slept with her every night. It is the stuff, quite nakedly, of fantasy, and still is today, as ten thousand pulp novels, photo shoots, and soft porn films will attest. Why then, in Book Five of Homer’s epic, does the god Hermes find Odysseus “sitting on a seashore . . . his eyes . . . never / wiped dry of tears”? What, in our terms, is the problem with the beach—a life lived beyond any necessity, with a love goddess whose collagen never loses its tensile strength?

The answer Homer gives is subtle and complex. Some of the first suggestions come before we even see Odysseus, in Hermes’ conversation with Calypso. He has come, he tells her, on Zeus’s orders alone:

I did not wish to.

Who would willingly make the run across this endless

salt water? And there is no city of men nearby, nor people

who offer choice hecatombs to the gods, and perform sacrifice …

Already, we can see that Calypso’s island, Ogygia, is extremely remote from human populations, and thus from politics and religion. Odysseus himself does not complain of these lacks, but Homer suggests they are part of the problem: a political animal will not be happy without people, without a polis. He is also without freedom, lying by Calypso every night “of necessity, / in the hollow caverns, against his will,” and this must make even a tropical paradise less desirable.

More surprising, however, is his rejection of Calypso’s two most tempting offers: immortality, and the pleasure of her changeless good looks. She wants to make him “the lord of this household / and . . . an immortal,” rather than let him go back to his merely human wife, Penelope, adding that she looks better than Penelope anyhow:

I am not her inferior

either in build or stature, since it is not likely that mortal

women can challenge the goddesses for build and beauty…

Tellingly, Odysseus quite agrees, yet still chooses his middle-aged wife, his mortality, and his nostos. Thus, Homer brings us right up against a mysterious fact: the fantasy of an undying beach body is not a thing that would really make us happy. But again, why not? Time has something to do with it: weeping on Calypso’s shore day after day, Odysseus feels the “sweet lifetime” (glukus aiôn) to be “draining out of him,” and yet he does not desire to escape the passage of time through an artificially imposed immortality. Rather, he wants to spend that sweet finitude with another mortal, his wife. The drama of freedom unfolding over the course of a finite life, and lived with others who share the same kind of drama: that, Homer suggests, is what humans were made for.

The drama of freedom unfolding over the course of a finite life, and lived with others who share the same kind of drama: that, Homer suggests, is what humans were made for.

If Homer is right, our dreams of the beach, however appealing on the front end, are bound to bring us to misery, for what we actually want deep down is to know, to love, to live, precisely as humans. We are contingent, historical creatures caught up in a high-stakes drama—and no other life is (for us) worth living. By the same token, the best kind of lover, friend, spouse, will have the same kind of skin in the game: skin that can age, that has aged, that is actively aging before our eyes. In moments of honesty, the restructured 50-something celebrities on screen strike us as unreal, cartoonish, faintly absurd. Like the homewrecker who ditches his wife for greener pastures, they reveal themselves as middle-aged artistes, playing at youth.

By contrast, a person with a history written into her body, his body, brings the weight, wisdom, and dignity of that history to every moment. To escape that history—the promise of Calypso—is to escape the meaning, the meaningful struggle, of our lives. At bottom, we are happier when we acknowledge this defining finitude of ours, and share it with other equally finite persons.

A person with a history written into her body, his body, brings the weight, wisdom, and dignity of that history to every moment. To escape that history—the promise of Calypso—is to escape the meaning, the meaningful struggle, of our lives.

“Ye shall be as gods”

To say as much is only to elaborate a point Homer made even more clearly in his war epic, the Iliad. There, Achilles, among many others, strives for glory on the battlefield, and in his striving, is frequently compared to a god. Some of the first words of the poem describe him as dios Achilleus, “godlike Achilles,” referring to the unheard-of mastery he enjoys in combat. At the high point of his dominance, Homer compares the man to a raging conflagration, more than human in his power:

As inhuman fire sweeps on in fury through the deep angles

of a drywood mountain and sets ablaze the depth of the timber

and the blustering wind lashes the flame along, so Achilleus

swept everywhere with his spear like something more than a mortal

harrying [the Trojans] as they died, and the black earth ran blood.

It is the apex of his transcendence, and yet Homer swiftly undercuts the hero’s brilliance by forcing us to see the grotesque, sub-human violence of the man:

Or as when a man yokes male broad-foreheaded oxen

to crush white barley on a strong-laid threshing floor, and rapidly

the barley is stripped beneath the feet of the bellowing oxen,

so before great-hearted Achilleus the single-foot horses

trampled alike dead men and shields, and the axle under

the chariot was all splashed with blood and the rails which encircled

the chariot, struck by flying drops from the feet of the horses,

from the running rims of the wheels. The son of Peleus was straining

to win glory, his invincible hands spattered with bloody filth.

In short, this spectacle, and indeed the whole of the Iliad, drives home the basic truth that, when humans strive to make themselves gods, they paradoxically lower themselves to the level of beasts. For Homer, in this sense at least, the first shall be last.

As Aristotle would later suggest, the terrain of human life is drawn out between that of gods above and beasts below. Homer clearly shows that acceptance of this intermediary position is one of life’s chief burdens: a tremendous struggle, certainly, but also a key to flourishing. On Calypso’s island, Odysseus’s temptation is a different version of the one that faced Achilles earlier. The choice he makes, finally—to go home to his wife—is nothing if not an acknowledgment of his humanity, an admission that he is not, and cannot pretend to be, a god. It is this decision that shows he is ready to complete his homecoming, and be most fully himself.

Our choice on the beaches of our own lives is the same: will I live as the human person I am, or try to arrogate for myself an impossible dominion? The hissing temptation is just as palpable now as it was for our first parents in the vernal depths of Eden. Will we let ourselves be what we are?

Now that we have come right up to biblical revelation, however, a final complication needs to be faced. Even as I assert, with Homer, that we must accept our own humanity, do I not implicitly cast shadow on the eternal destiny of the faithful? Are we not meant, by the work of grace, to share in the divine life forever, becoming like him as we see him as he is? Did not the Fathers love to speak of sanctification as a process of theosis, or deification? It would be a mistake to reject the divinizing urge entirely. Rather, it must be channeled, submitted, formed. On this argument, could we not say that the desire for Calypso, the desire for the ageless beach body, is simply a misplaced, malformed desire for God, and for the version of ourselves that finds its place and meaning fully in Him? Indeed, we must, though this detracts but little from Homer’s insight, properly understood.

When Adam and Eve took the prohibited fruit, their sin was to seize divinity willfully out of turn, rather than receive it as God’s gift in his own way, in his own time. Odysseus on Ogygia, and we on all the beaches of the world’s desire, face the same choice. Will we choose an impossible self-fashioning or a homecoming, across the infinite sea, to who we really are?