Laws reveal much about what a society values. Legal jargon is never just jargon: statutes and proposed legal amendments reveal foundational moral convictions about what is true, good, and just. It ought not to cause surprise, therefore, that when lawmakers propose new laws, a clash of worldviews ensues, and rhetoric emerges that reveals fundamentally disparate visions of how society should be structured.

The Equality Act is perhaps one of the clearest pictures of just how polarizing the legal code can be. One legislative act can thrust the nation into a divisive dispute over a priori moral and ethical questions—questions over what it means to be male and female, the institution of the family, matters of discrimination, and the issue of religious freedom.

The complexities of the Equality Act will continue to grip political discourse and debate in the months and, most likely, years to come. The act’s advocates contend that the Equality Act represents the keystone achievement of LGBTQ equality. As House Speaker Nancy Pelosi argued, the Equality Act resoundingly commits the United States to treating LGBTQ people equally not only “in the workplace, but in every place.” The act, however, also suffers its discontents, who rightly chide the legislative measure as an assault on religious freedom.

But is the argument about the lack of religious freedom protections enough? I think Ryan Anderson is right: religious freedom cannot be the only end sought by conservatives and especially for Christians. “The answer,” Anderson argues, “isn’t for our side to forfeit the fight about the truth by pleading only to be left alone.” Indeed, there are far more egregious consequences of the Equality Act than its lack of protections for religious freedom: it celebrates and legitimizes a way of life that is fundamentally destructive, both on an individual and societal level. There are serious matters at stake in the constellation of ethical issues connected to the Equality Act. Again, legal jargon is never just jargon. Codified laws flow from a worldview, and in the case of the Equality Act, the undergirding worldview is antithetical to human flourishing.

Start your day with Public Discourse

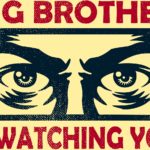

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.That is, perhaps, one of the more pressing and pervasive threats of the Equality Act: the freedom to think, to be offensive, to state publicly without equivocation or fear of retribution that transgenderism, as an example, is destructive. The editorial board of The Washington Post suggests that such views are permitted, but they must remain private—they cannot, for the sake of human dignity, have a place in the public square. Cancel culture devours dissent, as evidenced by Amazon’s removal of Ryan Anderson’s book against transgenderism, When Harry Became Sally. The Equality Act would not merely alter legal code. It would engender and nourish a burgeoning assault on any who publicly dissent from the new secular orthodoxy.

The impulse to silence and sideline dissent against a socially prescribed orthodoxy is not new. Indeed, the proponents of cancel culture and the advocates of the Equality Act embody an all too familiar impulse of the human condition.

Civility of Conformity in Colonial Massachusetts

The impulse to silence and sideline dissent against a socially prescribed orthodoxy is not new. Indeed, the proponents of cancel culture and the advocates of the Equality Act embody an all too familiar impulse of the human condition. The inclination to gag society’s dissenters stems from what I call the civility of conformity, which is a political ideology that prizes moral and ethical uniformity around a socially mandated orthodoxy.

Civility of conformity made its way to America in the earliest days of the colonial period. As winter’s chill began to descend in October of 1659, the colony of Massachusetts carried out the execution of William Robinson and Marmaduke Stevenson, two Quakers who disturbed the civil peace and threatened the purity of the church with their blasphemies and idolatry. The authorities in Massachusetts feared the spread of Quaker heresy throughout its colony, and Massachusetts colonists believed that they must faithfully maintain the law of God. In the preservation of God’s ordinances among them was their security and peace. In other words, religious establishment in this early American colony created no space for dissent. Conformity secured peace, ecclesial purity, and social stability.

Throughout the 1630s and 40s, Massachusetts navigated the Roger Williams controversy, the antinomian crisis, the Samuel Gorton case, and the Remonstrance of 1646. The rise of Protestant pluralism, coupled with the unrelenting conviction of dissenters, continued to undermine the colony’s efforts at uniformity. Not only that, but the colony suffered in each of these controversies a public relations catastrophe with England. News began to cross the Atlantic of the colony’s departure from the Anglican model of church governance, which violated its charter. Individuals like Thomas Lechford, for example, detailed the harsh antics of a colony that had dissolved into a chaotic spree of violence against nonconformists. Lechford chronicled how the colony banished, whipped, and imprisoned men for theological crimes “without sufficient record.” The assault on the aspiration and vision of Massachusetts’s Puritan divines led men like John Cotton, John Winthrop, Nathaniel Ward, and Plymouth’s Edward Winslow to defend the colony’s actions as well as to reassert the necessity of civility of conformity.

Sensing the need for representation in England, Massachusetts dispatched Edward Winslow to serve as its agent. He administered the colony’s affairs over various controversies, especially the case with Samuel Gorton, writing a lengthy defense of the colony’s actions as well as the colony’s legal and ecclesial framework. In his work, The Danger of Tolerating Levellers in a Civill State, Winslow sought to assuage English authorities’ concerns about the colony’s laws against religious dissenters. His advocacy came at a time in England when toleration was on the rise as a viable political option. Winslow stated that while those laws existed, the colony only used civil punishment against dissenters for cases of extreme obstinacy. Dissenters could “carry themselves peaceably,” without fear of punishment or persecution—but by “peaceably,” it was clear that Winslow meant “privately.” Thus, civility of conformity allowed for some measure of toleration that covered those who dissented from the established orthodoxy; tolerance, however, ended when private beliefs became public.

Civility of conformity was the mainstay political theology and the ideal pattern for Massachusetts’s colonial endeavor. Religious establishment inextricably tethered social flourishing to uniformity—a uniformity to a socially prescribed orthodoxy. Tolerance of deviance was unlawful and sinful. Their commitment to civility of conformity, which culminated in the executions of the two Quakers in 1659, demanded intolerance toward any and all dissent.

Evangelical Civility

There was, however, a rising competition to civility of conformity. Four years after the Quaker executions in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, in 1663, obtained from King Charles II a new colonial charter. This charter represented nearly a decade of work by the colony’s agent, Baptist believer John Clarke. Rhode Island’s 1663 charter embodied a fundamentally divergent conception of the interplay between church and state and codified a novel civil society in early America at odds with its Bay Colony neighbor to the north.

The charter depicted its social and legal arrangement as “a livlie experiment,” arguing that “a most flourishing civill state may stand and best bee maintained, and that among our English subjects, with a full libertie in religious concernements.” The inhabitants of Rhode Island would enjoy “the free exercise and enjoyment of all theire civill and religious rights.” The colony endeavored to offer a haven for distressed consciences that “cannot, in theire private opinions, conform to the publique exercise of religion, according to the litturgy, formes and ceremonyes of the Church of England.” It created an open public square marked by unrestrained consciences. Rather than conformity to a socially prescribed religious orthodoxy, the 1663 charter reimagined how a body politic achieved religious purity and social peace. Rather than coercion or conformity, it disentangled the colony from any religious establishment.

Under the leadership of Roger Williams, Rhode Island enacted a counter to civility of conformity: evangelical civility. Where leaders in Massachusetts equated coerced uniformity with social flourishing, their radical neighbors to the south fundamentally disagreed. Evangelical civility asserted that flourishing and peace were not secured through a coerced established orthodoxy, but the liberation of men and women to espouse their deepest convictions freely and publicly. Persuasion through rigorous and respectful debate was a far superior, indeed, Christian model for a civil society.

Thus, by the early 1660s in colonial New England, two bordering jurisdictions enacted disparate policies on the issues of conscience, religious freedom, religious establishment, and civility. One jurisdiction was prepared to execute dissenters, while another embarked upon a “livlie experiment” in liberty of conscience and disestablishment. These competing notions of civility—or, contests of civility—configured radically dissimilar visions not only of fundamental theological questions over soteriology, ecclesiology, and God’s decrees for civil authority, but also entirely conflicting approaches to political order. This contest of civility did not die in the early modern period and remains unresolved today.

Thus, by the early 1660s of colonial New England, two bordering jurisdictions enacted disparate policies on the issues of conscience, religious freedom, religious establishment, and civility. One jurisdiction was prepared to execute dissenters, while another embarked upon a “livlie experiment” in liberty of conscience and disestablishment.

A Contest between Conformity or Liberty

These two notions of civility undergird many of the present-day debates over not only religious liberty but freedom of speech. There is an unsettled tension between the pull toward conformity to a socially prescribed orthodoxy, on the one hand, and liberty of conscience, which guarantees the unencumbered and public expression of one’s beliefs.

Indeed, Roger Williams devoted much of his career to the idea of evangelical civility, that true human and social flourishing was possible insofar as citizens enjoyed the liberty to publicly express their deepest convictions. To be clear, Williams in no way supported notions of religious equality; he did not contend for religious liberty because he thought all faiths and moral convictions were equal. On the contrary, Williams spared little time in mincing words about Roman Catholics, Jews, and pagans, whom he described as individuals committing “spiritual whoredoms.” Notwithstanding his clear disdain toward what he believed were false religions, Williams was ready to defend their liberty of conscience. Without the freedom to think, to publicly profess, and to contend for one’s beliefs, society would eventually erupt in chaos and violence.

Persuasion, argued Williams, represented the clearest channel for civil societies to flourish. Engaging one another in debate rather than coercing dissent into submission not only engendered peace, but reflected a proper interpretation of the Scriptures. If the aim was to convert, then one was dealing with matters of conscience. God, according to Williams, never granted the civil state dominion over the human conscience; to penetrate that deeply into someone’s worldview and beliefs required the kind of influence only achieved through patient, respectful, and at times, contentious discourse.

The Equality Act and the vector of the sexual revolution, however, resemble the impulse undergirding civility of conformity. Dissent from the new socially prescribed orthodoxy is tantamount to sedition against the entire fabric of society. The Salt Lake Tribune, for example, ran an article arguing that those clamoring for religious freedom exemptions in the Equality Act were merely obfuscating their vile bigotry and discriminatory prejudice. The article says, “hiding discrimination behind religious doctrine is not new for the church. . . . It’s been argued that passage of the Equality Act could devastate religious schools. But [when schools’] historical treatment of LGBTQ students is egregious at best, why should we protect the institution?” The “treatment” by these institutions was merely holding fast to a traditional understanding of gender and sexuality. That is, according to this article, not only inexcusable but worthy of being silenced through the coercive power of the state.

Times are certainly different today from what they were in the 1650s and 60s. We are not talking about burning heretics of the sexual orthodoxy at the stake. What remains, however, is that perpetual contest between conformity and liberty. As debates over the Equality Act and related issues continue, it is important to highlight this perennial tension. Civility of conformity and evangelical civility represent two competing notions of flourishing and how best to order a society. They both cannot be right. This is a contest of civility. It is, moreover, a contest worthy of our engagement not only for the defense of religious freedom, but also for the preservation of what makes meaningful pluralism possible: persuasion, not coercion; freedom to think, not fear of retribution; and the liberty to engage in public discourse, not the silencing of dissent.