It might have been late morning when the stranger appeared.

He came from the river’s edge, where swaying reeds crowd the water. Not far off, the river runs obediently into the ocean; but here it is all fresh water, a pleasing place to bathe or wash clothes under the trees’ mottled shade.

Here the stranger, plainly in need, is met by a princess, of all people. As princesses never travel alone, she has some other girls her age about her, enjoying the escape from the palace.

What is a young princess to do when she meets an unusual person at the bank of a river? This one, many centuries ago in the Mediterranean east, was not afraid, but showed her best hospitality. She provided for the destitute one and even took him back to the palace with her, giving him all he needed and more. What she could not have known was how pivotal that encounter would be in their lives and others’. Nor could she have foreseen what tales would be told about it down even to our own times.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Now, depending on which ancient myths one has been reading, this meeting of princess and stranger may strike one as Greek or as Israelite. Of course, many unexpected encounters take place at the water’s edge, where two worlds meet, and not a few old-world princesses must have had such an experience. But the two best-known such narratives come from Greece and Israel. When we look at them side by side, letting their similarities and differences show themselves, a surprising unity emerges, as well as a fruitful tension. Both the unity and the tension are instructive. Indeed, these two ancient stories of royal hospitality converge on one of the deepest of all truths.

Odysseus the Cunning

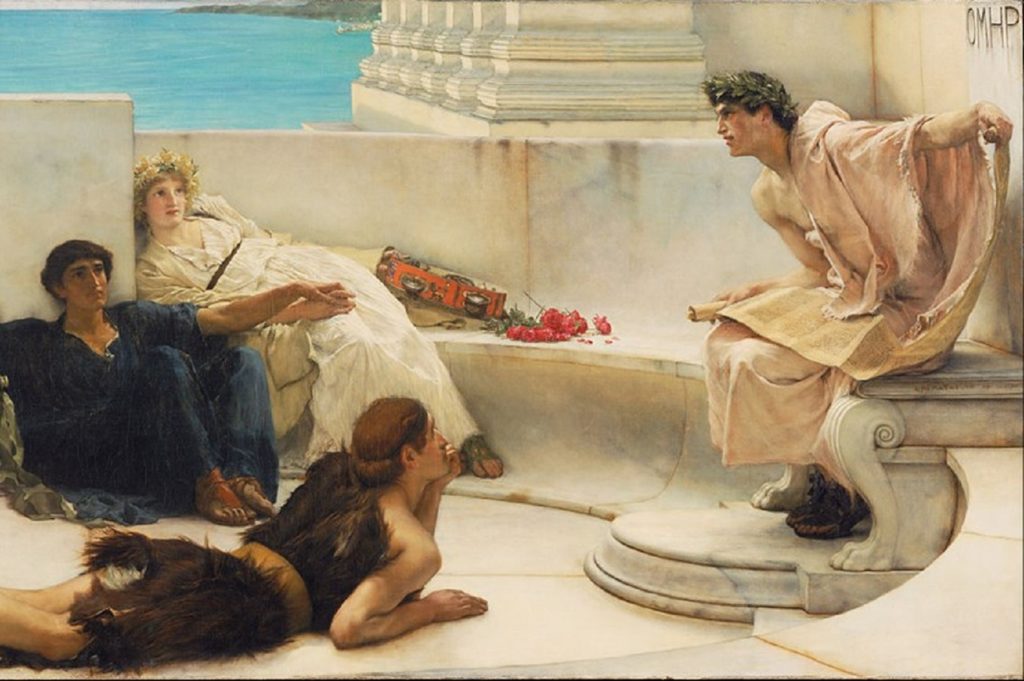

The first narrative is that of Odysseus, who washes up on Scheria, island kingdom of the Phaiakians, at the end of the fifth book of the Odyssey.

Stripped by a violent sea of his clothing and possessions, he crawls to shore and falls asleep under a pile of leaves. On waking the next morning, Odysseus hears maidens’ voices and emerges to find the princess Nausikäa and her companions. Their encounter is marked by wit, careful rhetoric, and a subtle sexual tension.

Most of the girls run away at the approach of the shipwrecked man, naked as he is and “all crusted with dry spray,” but the princess holds her ground. Odysseus considers, half humorously, “whether to supplicate the well-favored girl by clasping / her knees, or stand off where he was” and make his appeal “in words of blandishment.”

Wisely choosing the latter, he turns on all the charm a bedraggled, salt-encrusted castaway can muster. “I am at your knees, O queen,” he begins, “but are you mortal or goddess?” Complimenting her beauty, he appeals to her desire for marriage: “blessed at the heart . . . is that one / who, after loading you down with gifts, leads you as his bride / home. I have never with these eyes seen anything like you, / neither man nor woman.” Having secured Nausikäa’s attention, Odysseus explains his plight and asks for her pity. If she will help him and take him into town, he adds, “then may the gods give you everything that your heart longs for . . . a husband and a house and sweet agreement / in all things.”

The whole speech is a remarkable piece of rhetoric. Demonstrating his keen awareness of whom he is speaking with, Odysseus makes his approach via her strongest desires—to be appreciated for her youthful beauty and to find a spouse. He implicitly puts himself forward as a potential suitor: if you help me, may the gods grant you your husband.

His success establishes once again the power of Odysseus’s logos, his quick insight into others’ character, and his mastery of complex human situations. This stranger succeeds with the princess by virtue of his mind, his words, and his personal attractions.

Moses the Meek

By sharp contrast, the Israelite narrative in the second chapter of Exodus features a stranger with no such gifts.

The princess here is the unnamed daughter of Pharaoh, and the stranger is a child, the three-month-old Israelite infant Moses. Unable to walk, he floats up to the princess in a basket of papyrus, just as unhappy as one would expect an unattended baby in a makeshift boat to be. On opening the basket, the princess “saw the child; and behold, the baby was crying. She took pity on him and said, ‘This is one of the Hebrews’ children,’” a boy subject to death by her father’s decree. With the help of Moses’ attentive sister, the princess takes him in and arranges for all that the infant requires. “And the child grew . . . and became her son; and she named him Moses”—Mosheh in Hebrew—“because I drew him out [mashah] of the water.”

Moses has remarkably little to do with his own rescue. In place of Odysseus’s rhetoric, he offers only tears and wailing—brute expressions of physical need. In place of the Greek hero’s virile suggestiveness, he displays radical dependence. On the princess’s side, the reciprocal attraction of marriage is replaced by the more one-way attraction of motherhood.

In the narrative of Exodus, the watery stranger succeeds with the princess thanks to no wiles of his own, but to divine and human forces beyond his control or imagining. The contrast with Homer’s Odysseus is clear.

Moses has remarkably little to do with his own rescue. In place of Odysseus’s rhetoric, he offers only tears and wailing—brute expressions of physical need. In place of the Greek hero’s virile suggestiveness, he displays radical dependence.

Greek and Hebrew Heroism

The two stories do share some important similarities. In both tales, royal hospitality (Homer’s xenia) makes the difference: a needy stranger is ushered into the wealthiest, most privileged sector of an alien civilization. Each encounter leads to a new birth for the stranger’s people: the Phaiakians load Odysseus down with gifts and send him back to his kingless people in Ithaca; the family of Pharaoh gives Moses a royal upbringing, enabling him to become the leader his own people so desperately need. In each the blessing of human hospitality is made possible by larger divine influences: Zeus and Athena on the one hand and the Lord GOD on the other. Finally, each is followed by episodes of violence: Odysseus picks a fight with his wife’s suitors once the Phaiakians bring him home, and Moses kills an Egyptian slave-driver after coming to his maturity. The two accounts are marvelously parallel.

Even so, their divergences point to fundamental philosophical and theological differences.

Consider the startling passivity of the Hebrew stranger, a three-month-old capable of nothing; his very name is “he who was drawn out.” His type departs remarkably from Homer’s heroes and their impressive strengths (there are no stories about helpless infants in Homer), but it is utterly characteristic of biblical revelation. The Bible teems with babies, widows, the disabled, and otherwise radically dependent people, none of whom is quite up to the task of living.

Why is the human protagonist of Exodus passive? To show forth the glory of the tale’s far greater divine protagonist. This point reflects the second major difference between the narratives: the role of providence. Odysseus, for all his neediness, dominates the scene with Nausikäa. In Exodus, not Moses but God controls events, invisibly orchestrating multiple human instruments in the song of Israel’s salvation. Underlining the priority of divine agency, the text places the infant Moses in not just any basket, but a tevah, or “ark,” calling to mind the Flood of Genesis. Moses, and later his people, are saved from threatening waters just as Noah was, by an unlikely divine intervention.

Finally, the Exodus plot aims toward a fundamental peace that is not hoped for in Homer. Because the success of Odysseus and his people depends in great part on his actions, his own exercise of force, we never quite get past human competition and the threat of conflict. Odysseus is dominant now, but someone else will be soon. In Exodus, the violence of the plagues, the slaughter of the first-born, and so forth, lead clearly toward liberation, the Promised Land, and ultimately Heaven. In God’s providence, temporal violence happens for the sake of eschatological peace.

The Bible teems with babies, widows, the disabled, and otherwise radically dependent people, none of whom is quite up to the task of living. Why is the human protagonist of Exodus passive? To show forth the glory of the tale’s far greater divine protagonist.

The Stranger on the Shores of Eternity

The stories of Exodus and Homer suggest that we must choose between passivity and activity, peace and violence. Two roads seem to diverge here, each with its own basic anthropology and metaphysics. But the question becomes more complicated, and more interesting, when we turn to the princess-and-stranger narrative to end all others: the Incarnation of God the Son as Jesus of Nazareth.

With astonishing synthetic power, the Incarnation story recapitulates both of its forerunners and combines them. Its stranger is Christ, come among those who know him not. Like Moses, he comes as a baby looking for a mother, Mary, and through her he finds the rest of us. Like Odysseus, he comes calling as a suitor; but unlike the wily Greek, he makes good on this appeal, taking the Church as his Bride. Having emptied himself and taken on the weakest human form, the infant Jesus is, like Moses, subject to everyone: like all the great biblical protagonists, he comes as one of the least among us. And yet, like Odysseus, he rules the world by the power of his word.

As St. Ephrem the Syrian put it long ago:

Blessed is the One Who dwelt in the womb, and in it He built

a palace in which to live, a temple in which to be,

a garment in which to be radiant, and armor by which to conquer.

At the shore of our own experience he is arriving, even now—on the tidewaters of the sea of eternity. He rides within the ark of the Church, and yet walks free upon the flood. Odyssean in his strength, Mosaic in his self-emptying weakness, he seeks to be our guest “today,” where the eternal meets my time and yours. He makes himself a stranger, for no prophet is welcome in his native place. He asks for lodging so that he can bring us to a home beyond the dreams of any princess. He seeks from us what little we can give, so that he can give us everything.