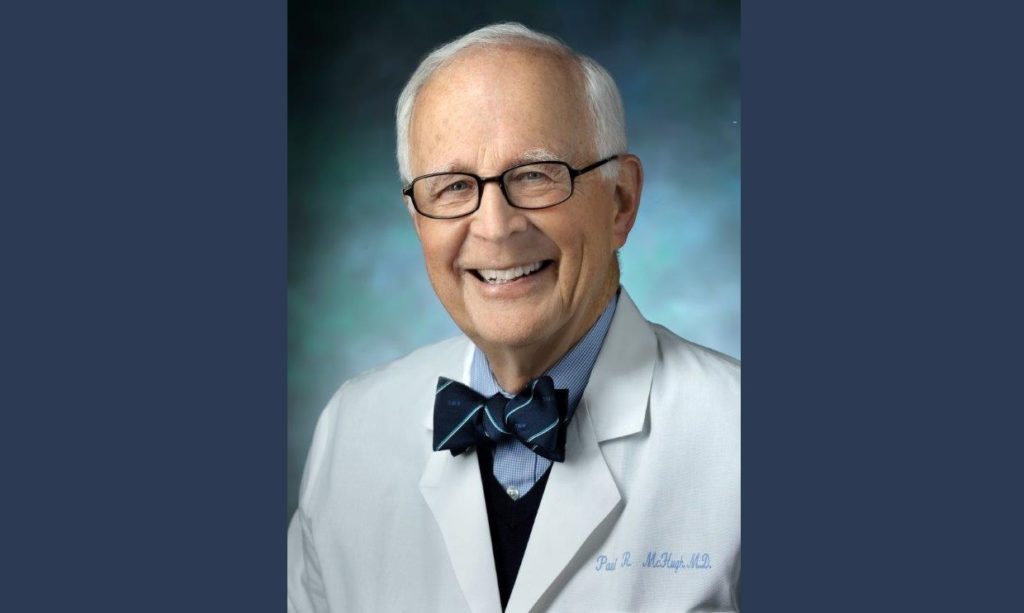

Dr. Paul R. McHugh is University Distinguished Service Professor in the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, where he served as Director of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and Psychiatrist-in-Chief at Johns Hopkins Hospital from 1975 to 2001.

In a distinguished career that began with his training at Harvard Medical School, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, Dr. McHugh has taught at Cornell, the University of Oregon, and since 1975 at Johns Hopkins. He was the co-creator of the Mini Mental States Examination, one of the most widely used tests of cognitive function, and he sponsored the work that resulted in The 36-Hour Day, a bestselling guide for families and caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s and other dementia conditions. In the 1980s and 1990s, Dr. McHugh and Dr. Phillip R. Slavney published The Perspectives of Psychiatry and Psychiatric Polarities, which may be said to have embodied the tenets of the influential “Hopkins School” of the discipline. For the wider public, Dr. McHugh has published on psychiatry—both its findings and its failings—in The American Scholar, First Things, Commentary, Public Discourse, the Weekly Standard, and The New Atlantis. His books for general readers are The Mind Has Mountains (2006), a collection of his essays, and Try to Remember (2008), which concerns his role in debunking the “recovered memory” fad in psychotherapy. In 2015, the Paul McHugh Program for Human Flourishing was established in the Johns Hopkins Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences.

I note that Dr. McHugh is not Professor Emeritus at Johns Hopkins, which is worth remarking upon because this week he turns ninety years old. He is still a full-time faculty member in the university’s school of medicine—teaching, mentoring psychiatry students, and caring for patients. We spoke on Monday after he had spent the morning in the psychiatry department’s weekly grand rounds.

Matthew Franck: In Psychiatric Polarities, you and Phillip Slavney wrote that “mental life is dependent on the brain. . . . Yet mind and brain are not identical. Indeed, they are so different that the nature of their relationship is the fundamental mystery in psychiatry and the source of many of its conflicts.” Would it be fair to say that the successes of modern psychiatry stem from work that recognizes this mysterious relationship of mind and brain, while its failures stem largely from therapeutic interventions that ignore this mystery or try to explain it away?

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Paul McHugh: I think that mystery remains a great mystery, but is perhaps best resolved at the moment by seeing mental life as an emergent property of the brain. It emerges from it, but it doesn’t emerge as smoke; it remains an interactive process. There are some aspects of human disorders and human mental life that depend upon the brain for their sustaining, but they don’t depend upon the brain for their generation—things like grief, and maybe post-traumatic stress disorder, and things of that sort. They depend upon an appreciation of the person, of what was there and was lost (for grief), or what was there and was frightening (for PTSD). The brain follows the mind in that way. So the fact is that the narrative capacity of the human mental experience can be the source of various forms of psychiatric distress that psychiatrists try to help the patient both understand and perhaps re-script in a way that makes living with it more easy. And none of that actually depends upon the psychiatrist directly tinkering with the brain’s substance or the material itself.

So when we were, in the Polarities, saying that this is the issue, these two things, we didn’t mean to say that everything that the psychiatrist could successfully do would depend upon his working with the brain. He could make lots of mistakes there, as the frontal lobotomy experience demonstrated better than any, and then some abuse of medications today demonstrates. But he could also make mistakes in the narrative by presuming things that were not there in actuality but were put in by him, or her, the psychiatrist, because they made a better story. I don’t think all the mistakes that psychiatrists make are related either to the area of the brain they work in or the area of mental life and its trajectory. They can make mistakes in both places.

MF: I know that you and your colleagues at Hopkins have really merged these questions in neuropsychiatry so that you’re attending to both brain and mind. But there have been schools of thought in psychiatry that emphasize one overwhelmingly at the expense of the other.

PM: Yes indeed, and that is the thing that we’re trying to avoid by making it clear that there are different methods that employ one or the other, or sometimes both together in a coherent way. But you know, I did train in neurology as well as psychiatry. My teachers made sure that at least I was exposed to the ideas on both sides of that very interesting emergent property.

MF: In one of your essays in The Mind Has Mountains, you observe “the power of cultural fashions to lead psychiatric thought and practice off in false, even disastrous, directions.” Two such fashions that captivated psychology and psychiatry in recent decades were “multiple personality disorder,” also known as “dissociative identity disorder,” and the idea of “repressed sexual memories” from childhood that adults can “recover” under therapy. What accounts for such therapeutic fevers gripping the mental health professions?

PM: That’s a very good question. I’m not sure I understand why we’re so vulnerable to this. It may well be in part that we are a discipline that cannot often use bodily material, like an autopsy or something, to prove ourselves right or wrong. We have to use the power of persuasion to persuade patients and others to thinking the way we want them to think. And although that’s the fundamental principle of psychotherapy—psychotherapy is a persuasive enterprise, after all, that’s what it is, it’s nothing else but persuasion—persuasion, not only in psychiatry but maybe even in a democracy, its great vulnerability, as Tocqueville said, is the tyranny of popular sentiments. The tyranny of popular opinion can hold in thrall a whole population, after all, for a while. I think psychiatry is vulnerable to that because it works with phenomena of mental life and problems of mental behavior, and therefore is liable, without another kind of tradition or another source of knowledge, to be carried away. It happens about every ten or fifteen years.

MF: I recall your saying as well in that book that psychiatrists don’t have the sort of grounded reality of specializing in the skin or the eye or something about which there cannot be endless arguments once the evidence comes in.

PM: That’s right. The material evidence of the physical body has a great salutary effect on people who have strong opinions about things, as William Osler said long ago. He said, you know the great thing about the consultant is, he comes in and does the rectal that you forgot to do. The great thing about doctoring is that it’s a fundamental business; you stand on the bottom of life, and it’s one of the joys of it. Why, though, psychiatry gets swept by these fantasies is still a further question. In part, I used to just think it was the Freudian commitment to suspicion of other people and of society and everything—it was one of the schools of suspicion—

MF: Sure, that there’s a dark id everywhere you look.

PM: That’s right, that somehow or other we’re always under the control of somebody else. Nietzsche and Marx and Freud were all of the same kind of caliber. I used to think that. I also think there’s a love on the part of psychiatrists for being men of the secret and having their own magical secret. If somebody comes along and tells you “Here’s a wonderful magical secret that will open to you the nature of the world and the nature of humankind,” it’s usually silly in the long run. That’s usually picked up by people who have no traditional background of their own. After all, it’s a kind of golden calf; you come down from the mountain and really try to bring them something, and what do you find them doing? Dancing around the golden calf.

MF: The appeal is to make some idol of a solution to some big problem.

PM: That’s right. And although Moses thought it was only his people, his people were—are, of course—all of us.

MF: In 2016, you and Dr. Lawrence Mayer published a 143-page monograph in the pages of The New Atlantis titled “Sexuality and Gender: Findings from the Biological, Psychological, and Social Sciences.” This publication generated a good deal of controversy, coming not long after the Supreme Court’s creation of a constitutional right for same-sex couples to marry, and just as the issue of “transgenderism” was beginning to heat up. What prompted you and Dr. Mayer to undertake this project, and what should we take away from it?

PM: I was prompted by the idea that I ought to at least say something in this matter, because so many ideas were floating around, and if I couldn’t speak, who could? And when I looked at the scientific evidence of these things, the very idea that these things were immutable, and discrete, and people were “born that way,” it didn’t work from the science point of view, and they might, in our society, not be such good ideas, not good things for people to believe. So I thought, “Well, if I can’t speak at my stage and my development, nobody can speak, and I’ll see what happens.” So, it was very interesting. I found it extremely interesting.

It caused a ruckus, and that didn’t surprise me. But what did surprise me was how many people would say, well, you know, “This is just wrong,” but would never show me any evidence. Dean Hamer, whom I have admired and thought of as a very coherent geneticist and student of homosexuality down in NIH, said “This has all just been disproven, it’s bad science,” but he never pointed out anything or said, “Here’s the article that proves it.” He was saying, “Look, this is the way we read the science today,” and he spent a lot of time talking about how this wasn’t a peer-reviewed article. Of course it wasn’t a peer-reviewed article. It wasn’t intended to be put out into the science literature. It was to try to evaluate what we thought the science literature taught to the ordinary public, like somebody would write in the New Yorker. And the useful way to refute such a thing is not to say “Those guys are stinkers!” or something. They should say “He’s overlooked something, and here’s the thing that he’s overlooked.”

It turned out that afterwards—long afterwards—people would say, “Well, you know, he’s right, but he shouldn’t have said it.” What it came down to was “He should have kept his mouth shut.” The reason they keep saying it is the usual explanation for not wanting to get all the truth out—that somehow it’ll encourage people to abuse other folks. Of course, we didn’t want that, and we don’t think that the truth is going to lead to anything other than further truth, as things go on.

MF: And better treatment of people. It’s interesting to me that you brought up that critique of peer review, because I had a follow-up on that front. I heard that a lot too when that long piece came out, that The New Atlantis is not a peer-reviewed journal, or that the work you and Dr. Mayer did was not peer-reviewed. And my first thought on hearing that was, well, of course not, what you and he did was the peer review. That is, you two, very knowledgeable in your field, did a comprehensive survey of studies in the field that had been peer reviewed in order to draw conclusions for a wider public about what we know and don’t know about sexual orientation and gender identity.

PM: It seemed to me they just didn’t want the conversation to go on. This way of calling it not peer-reviewed was to say that I was saying something that was supposed to be a new discovery. I wasn’t saying anything new, I was saying “This is how I read the literature.”

MF: People who dispute the way you and Dr. Mayer read the literature should not just say, “Well, that’s bunk.” After all, you were not reporting your own research but that of many, many others. They should point to these and those studies that you draw conclusions from and either show why they’re wrong or why you’re drawing the wrong conclusions from them.

PM: That’s right, and that’s what we said at the end of our article. We knew it was going to cause a fuss. Okay, go at it, and tell us what’s wrong.

MF: The bottom line of the monograph, it seemed to me, was that we still don’t know a great deal about the provenance of homosexuality and transgender or gender dysphoria. We have no particular reason to believe that either phenomenon is innate or biologically based or immutable.

PM: That’s right. Especially not immutable. That’s the most important thing.

MF: In a later piece in The New Atlantis, in 2017, you and Dr. Mayer were joined by Dr. Paul Hruz, a pediatric endocrinologist, in cautioning medical professionals against using puberty-suppressing drugs with children who present with gender dysphoria. Given the increasing incidence of patients presenting such psychological symptoms since that time, especially adolescent girls who wish to transition to “being” boys, as Abigail Shrier has written, this looks like it was a very timely intervention on your part. What is the concern, exactly, with these puberty-suppressing drugs?

PM: They come at a time when the person, the child, is not prepared to think about what their life would be like. Remember, puberty occurs between nine and fourteen when you’re a girl, and between eleven and fourteen when you’re a boy. These are children.

Anyone who’s had a ten-year-old girl or boy around knows that he or she is under your protective wing, in the sense not only of making sure he or she eats and is not abused today, but that he or she doesn’t make a mistake in their own decisions that will reverberate forever for them. We don’t let them get tattooed, we don’t—I wouldn’t let my daughter have her ears pierced until she turned sixteen. So these are very young children.

Secondly, this is a very complex process, puberty. Puberty is one of the great transforming neuro-endocrine events in anybody’s life. And we know only some parts of it; we do not know, for example, what triggers puberty. Back in 2005, the journal Science published its, I think, 125th anniversary issue, and they said, here are 125 big problems that remain for science. One of them was “What triggers puberty?” It’s a big mystery. But one of the things we do know is that the human being is very different from the ordinary animal. With the animal, if they successfully go through puberty—and they go through it rather young—at the end of that, fundamentally, they are the complete being that they’re going to be. With human beings, some of the most interesting individuating characteristics of themselves occur only after puberty, probably with a combination of the intellectual powers and the energy that sexual development brings.

So I don’t think any child—and any parent, for that matter—can make an informed consent to permit the blocking of puberty and the transmission of another sex. That’s the first thing: you don’t have an idea what you’re doing. So how can you have an informed consent about it? Because nobody knows.

As important, and a reason for thinking that judgment is affected, is that children, young people, who believe that they belong in the opposite sex, if permitted to go through puberty normally, 85 to 95 percent of them will at the end of that time say “No, I am who I am.” But if you give them the puberty blockers at age nine or ten, only 5 or 10 percent at the end of that time will say “I don’t want to go on further.” They always want to go on further. Something has changed in them. One of the things that change must be the way their brain is shaped when this triggering comes along for puberty. It gets thwarted. And the idea that it’s all reversible, that’s still very debatable.

Finally, the most important point is that scientists have one great vulnerability. They can be dealing with the most complex issue and try to oversimplify it and make it seem like a simple issue. In this case, we want to make a boy look like a girl—okay, so we’re going to do it with these hormones. Wait a minute: you don’t know this is a complex issue of the brain, neuro-endocrine relationships, hormones and—things that Paul Hruz knows even better than I. This very, very complex thing is being over-simplified.

MF: And there are real physical detriments that can come about in terms of bone mass, fertility, growth to mature height, all sorts of things.

PM: And who, at age eleven, knows? You might lose your fertility at age eleven; well, okay, you don’t know quite what that is. You might not know, given the other kinds of pressures that come into play. We don’t know all the pressures that are behind this gender dysphoria epidemic that we’re having, but we do have a lot of reasons for believing that social pressures on vulnerable and suggestible young people are at play there.

MF: In your own career, you’ve been standing athwart this for a very long time. In 1979, a few years after you came to Johns Hopkins, you directed the closing of the university hospital’s gender identity unit, responsible at that time for what we then called “sex-change operations,” and now it’s fashionable to call “gender-affirming surgeries,” after finding that such surgical transitions did not improve the overall mental health of patients. For this alone, you have been on the “enemies list” of transgender advocates for a long time. (Such surgeries were resumed at Hopkins in 2017.)

You have likened our “transgender moment,” as Ryan Anderson calls it, to other psychiatric fashions that ultimately collapsed under the weight of evidence against them—or due to the dearth of evidence for them. Transgenderism seems to be at peak strength today, in medicine, law, and public policy. Are you still sanguine about its ultimate collapse, like that of other culturally based phenomena in mental health sciences?

PM: I’m amazed at the amount of power and weaponry that it’s gotten behind it now, with the government and law and even medical organizations getting behind it, but I’m absolutely convinced that this is folly and it’s going to collapse, just as the eugenics folly collapsed. Eugenics was quite as powerful, after all. I’m reassured that we psychiatrists have been everywhere before. Fortunately, Adolf Meyer, my predecessor at Johns Hopkins, was one of the few psychiatrists in the world, really, who said “I don’t think we can go this way with the eugenics movement.” And so I feel I’m in good company by saying this is going to collapse.

It’s going to collapse, particularly, in relationship to the injury to children, because these people are already beginning to build up evidence for the misdirection they were sent on. In Britain, the Keira Bell case that has just been handed down from their High Court is recognizing the very inadequate psychiatric approach that was taken to leading this girl to now be a very damaged person. So it’s coming. And what’s going to happen in my opinion, at least with the young, the people under the age of twenty-one, will be that there will be huge lawsuits.

I can tell you exactly how the suits are going to play out. You know that person is going to wake up at age twenty-five and realize that that she’s got a five o’clock shadow, she’s had various mutilations in the body, she’s infertile, and she’s going to say, “How did you let this happen?” And then parents are going to say, “Well, the doctor said…” So they’re going to say “Let’s sue the doctors.” They’re going to go to the doctors and say “What did you do this for?!” They’ll say, “That was a standard treatment for transgendered,” and the person is going to say, “But you see, I wasn’t transgendered, I was a child!” And they’re going to say “Holy smoke, you’re right, we can’t tell who’s transgendered, in truth.” And then the insurance companies are going to bail out, and a lot of people are going to be injured in reputation. But we’re going to be left with a number of much more injured patients. I’m very sure this is going to happen.

MF: In one respect, it almost seems as though psychiatry has confessed its lack of any answer to the problem of gender dysphoria and farmed out the solution to the endocrinologists and the cosmetic surgeons. They’re inviting those specialists in other fields to tinker with the body to conform to a dysphoria in the mind, rather than treating the dysphoria in the mind, which is the province of psychiatry.

PM: Exactly. And by the way, when I did actively close down the psychiatric role in permitting the gender surgery—after all, I couldn’t stop the plastic surgeons from doing it if they wanted—I just was saying that we in the department of psychiatry were no longer going to endow it with our permission. One of the plastic surgeons came up to me and did say, “Oh, thank goodness. How would you like it to get up in the morning, Paul, and face the day slashing away at perfectly normal organs, because you guys don’t know what’s the matter.”

MF: That’s interesting! So what you had the power to put a stop to was the referral to the surgeons.

PM: That’s right.

MF: And the surgeons would not proceed without it.

PM: That’s right. And the reversal [in 2017] was that the plastic surgeons came and said we’re going to take this up again. They didn’t wait for our permission to open a clinic at Johns Hopkins. In psychiatry, I was no longer the director, and our department didn’t fuss about it.

MF: So the resumption in 2017 was not owing to a decision in psychiatry but a decision over in surgery.

PM: That’s it, a decision over in plastic surgery. The nice thing is, the director of plastic surgery came and told me he was going to do it. But it was their decision, not ours.

MF: A slight change of topic here. As someone who has been a faithful Catholic his whole life, you have sometimes been characterized—I would say uncharitably—as a man whose professional outlook is unduly influenced by his religion. But the Catholic Church teaches, as you and I both know, that there is nothing science discovers that contradicts the faith. So what is really going on when this charge is aimed at you?

PM: I’m always surprised by that. I’m told that my views about repressed memory, that that was going to protect Catholic priests from being punished for abusing people. I never said that the truth wasn’t the truth with those men. I’m always very surprised by this charge.

I do say that I am an orthodox Catholic guy. Thank goodness I was raised with it, because of the wonderful Catholic realism that places you solidly on the ground in relationship to human nature and the human condition. But I never thought that in this area, it was my religion that was determining how I would think about it.

I suppose I have to say that when I was first fascinated by psychiatry when I was at the Medical School at Harvard, it might have been the relentless attacks by the Freudians on the nuclear family that shocked me, because I felt that the nuclear family was the source of all kinds of wonderful reflections on each other that permitted one to go out into the world. Instead, the suspicious Freudians saw it as a place of dominance and the like. That may well have had something to do with my devotion to both my family and to the Holy Family that I had grown up thinking of as models. I would have thought if somebody wanted to say, “Look, his religion shielded him or protected him in this way, or blinded him in this way,” that would be an interesting conversation to have. But what does a tradition, a Judeo-Christian tradition, in particular, that honors the father and mother—how does it come at a discipline in medicine that begins to say that that’s the source of all your mental troubles?

But in these other matters, no one can say what aspects of oneself affect how you think about a problem. Obviously, we’re creatures ourselves, and a lot comes out of where we are and who we are, and we don’t always completely know. But I believe that my positions on these matters, on these matters in particular, relate to the science and the psychiatry that matters. And that anybody of any persuasion or no persuasion at all will eventually come to agree with me.

I do say that I am an orthodox Catholic guy. Thank goodness I was raised with it, because of the wonderful Catholic realism that places you solidly on the ground in relationship to human nature and the human condition.

MF: Yeah, “He’s a Catholic psychiatrist, therefore . . .” seems to me to be a deflection from the discrete issues that should be directly tackled on the evidence and the arguments. Of course, there are many people in your profession, who are Jewish or Protestant or have no particular faith, who agree with you on the fundamental questions you’ve worked on in your career. But what you’re saying is that your Catholicism has actually made you in some respects a stronger, better scientist.

PM: I’ve always thought so. I think Christianity was the foundation of science. After all, “In the beginning was the Word”—the Logos. Well, that means something, to make science reasonable. That’s what I’ve always thought. But you know, I’ve been amazed, because I’ve been attacked this way now, even at Hopkins—which is a wonderful institution, by the way, and it has for the most part protected me. And I didn’t have these kinds of things said about me, at least right out, since I was in high school. So it was a big surprise. Although I’m sure that anyone would say that, as you go through life, you don’t know what other people are thinking about you.

I had a very funny one: when I was admitted to Harvard Medical School, I had to have an examination by one of the doctors there—a physical exam to make sure I was well and all. They did that for every medical student. And about ten years later I happen to come across my record that had been written by this chap, one of the doctors in Boston who said, “rosy-cheeked Irish boy who’s done well to come as far as he has.”

MF: I think we’ve found the title for our interview: “Rosy-cheeked Irish Boy Who’s Come a Long Way.”

PM: That was pretty funny. I mean, it does show you the climate that you’re in that you didn’t realize. I had no idea this was crossing his mind.

Medicine is a humanistic discipline that uses science to accomplish what all human beings would like to see for themselves, in their capacity to sustain themselves. But ultimately it is to aim for a person who could be what God intended him to be.

MF: One last question. Tell us, please, about the work of the now six-year-old McHugh Program for Human Flourishing. What do you hope that it will contribute to the future of psychiatry and to public understanding?

PM: I hope it’s going to be a rich contribution at the end of my career at Hopkins. My aim is to point out, and to help young psychiatrists, and all doctors for that matter, to understand that after you get somebody over a condition, often they have still a ways to go to be the kinds of people that they were intended to be when they were started off.

What began, for me, as a kind of public health hygiene, mental hygiene for the patient—saying “Look, this is the kind of thing you’ve got to do, you’ve got to think in terms of family life, work life, educational life, and community, and particularly often religious life, to be what you want to be”—has now transformed itself into an understanding of where the education of doctors tends to fall down. It tends to fall down in the very areas of the humanities and the understanding of human capacities that doctoring used to be founded on, before the sciences could really take it up and make it go. So I’m hoping that people will see that an understanding of what human beings really can be emerges out of helping them through their physical as well as their mental illnesses, but then requires a continuing prescription for how they can continue in that way. And this way, I think, it will enrich the education of doctors in general, just like I think our Perspectives of Psychiatry has helped enrich an understanding of medicine in relationship to the conditions that afflict people mentally. So we’ve had a wonderful experience with it.

MF: Human flourishing is not a typical phrase in the vocabulary of medical professionals.

PM: It was a term that seemed to me to be the appropriate term. By the way, several people in my department thought it was a very Catholic term, I was surprised to see.

MF: If they think that Aristotle belongs to the Catholics, I guess we’ll take him.

PM: Right, that’s what I said to them, I thought it goes back to Aristotle.

MF: It’s a humanistic enterprise.

PM: It’s a fundamentally humanistic enterprise. Medicine is a humanistic discipline that uses science to accomplish what all human beings would like to see for themselves, in their capacity to sustain themselves. But ultimately it is to aim for a person who could be what God intended him to be. And, of course, it’s illuminating for me, like anything else in teaching. Once you start off on this, then you discover all the things that become important for yourself to learn.

MF: One really final question, for the record: Dr. Paul McHugh has no current plans to retire, correct?

PM: No plans to retire, no! Not me. I’m pressing on. I’m not retiring. I can’t carry on quite as much as I could before, but for the duties that I’m doing within the department, which are full-time for me, I’m going to continue as long as I can.