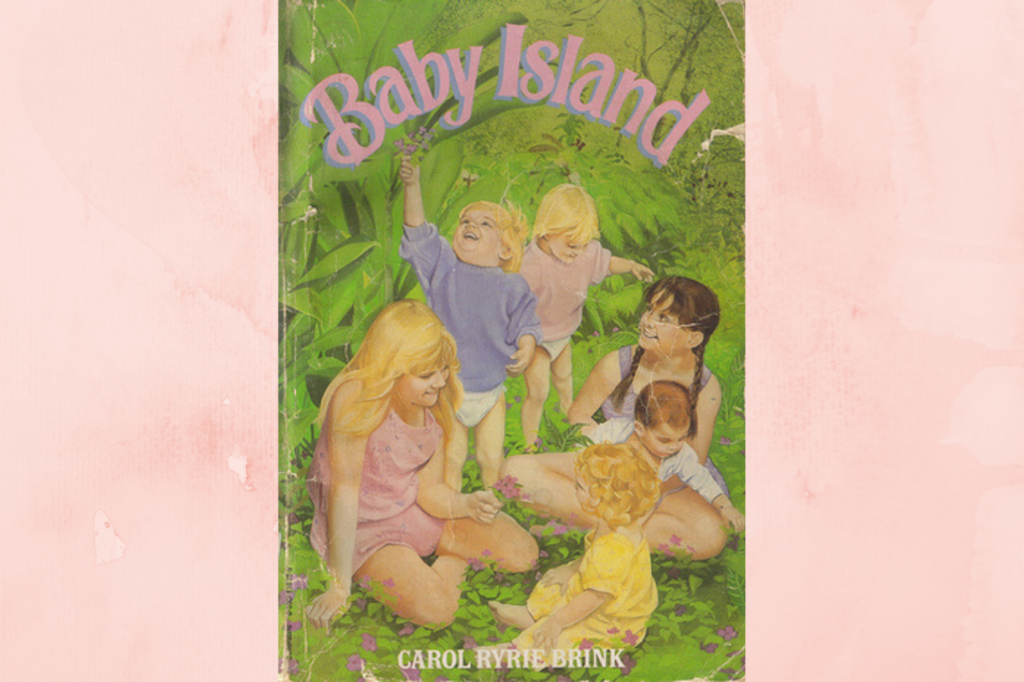

Examples of the bankruptcy of contemporary imagination abound. If we must choose just one, we could revisit a blip in 2017. It came to light that a cinematic remake of William Golding’s Lord of the Flies was in the works, with the twist that the cast would be all-female. Excitement, jokes, and criticism followed, but no one pointed out that it had already been done. The girlification of the “kids on an island” concept was undertaken and completed back in the book days, in 1937. In fact, Carol Ryrie Brink’s Baby Island predated Golding’s famous work by seventeen years.

Like Lord of the Flies, Baby Island leans on the 1857 children’s Robinsonade The Coral Island, by R. M. Ballantyne. Ballantyne’s ur-text shipwrecks three teenage boys, who triumph over nature and primitive man on an island in the South Pacific. It is subject to every criticism of the British empire: too colonial, too Christian, too male, too white, and too successful.

Golding and Brink each address one of these criticisms. Golding objected to the Coral Island boys’ success. He based Lord of the Flies on a set of circumstances and characters similar to Ballantyne’s, intending to show what would really happen if a crowd of boys were marooned. In Baby Island, Brink executes the all-female remake. She establishes the connection between the books with broad allusions to The Coral Island, beginning with the comparable titles. Mary and Jane Wallace, her twelve- and ten-year-old sister protagonists, shore themselves up in wobbly moments by singing “Scots Wha Hae,” reflective of both the national pride that drives Ballantyne’s boys, and the nationality of Ballantyne himself. The girls observe the Sabbath as well as they can, echoing the overt Christian piety of the boys on Coral Island.

However, Brink’s reimagining of The Coral Island is more perceptive than Hollywood’s, and less likely to gain approval from contemporary proponents of bland girl power. Rather than simply turning the involuntary islanders female, she gives them a uniquely feminine challenge. Mary and Jane do not have to worry much about provisioning. They arrive at their island in a stocked lifeboat that includes a store of food and other useful items. But in addition to Mary, Jane, and supplies, the lifeboat also contains four babies. The girls of Baby Island do not have to spear boars or devise a polis. Rather, they must keep house and take care of people.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Brink’s approach is not the slavish duplication of circumstance that maxes out the creative reach of the post-feminist mind. She gives her characters a congruity of trial with respect to person and nature. Mary and Jane face a challenge fitted to them as girls, just as the boys of Coral Island face a challenge fitted to them as boys. Each set of castaways meets a proleptic crisis of adult integrity. Can Coral Island’s boys live as men? Can they feed and shelter themselves, engage in both the diplomatic and martial aspects of statecraft, and even bring help and protection to those in need? Can Baby Island’s girls live as women? Can they make the most of the resources available to them, remain cooperative and kind to each other under tremendous strain, and prioritize the well-being of the vulnerable people entrusted to their care?

Can Baby Island’s girls live as women? Can they make the most of the resources available to them, remain cooperative and kind to each other under tremendous strain, and prioritize the well-being of the vulnerable people entrusted to their care?

Mary and Jane are not done being tested. Woman cannot live by babies alone, and the nautical pantry can’t fill itself. Footprints in the sand lead the girls to Mr. Peterkin, a man who lives alone on the island by choice. Mr. Peterkin is more than able to continue supplying the babies and their caregivers, if only he can be persuaded to do so. Mary and Jane do not fall sobbing onto his premises, claiming childish entitlement to their own rescue. They must up their game in the interest of the babies, and they know exactly how. They are pleasant and helpful. They put his house in order, improving his conditions considerably. They do not argue with his gruff refusal to help them, but quietly persist in providing services, being present, and exhibiting the babies when they are most clean and cute. This politic approach convinces cantankerous, hermitic Mr. Peterkin of his duty to society. He takes up the role of ad hoc paterfamilias with some reluctance, having been shown that he has no good reason not to.

“An all-women remake of Lord of the Flies makes no sense because . . . the plot of that book wouldn’t happen with all women,” tweeted Roxane Gay in 2017. But the plot of the book also wouldn’t have happened if Piggy had been cool, or Jack had been magnanimous, or if there had only been three boys, or if they had arrived in stocked lifeboats, or if there had been someone else on the island. Lord of the Flies is less a commentary on masculinity than it is on the humanity of children and the nasty side of hap. And while a female Lord of the Flies might be a mildly interesting thought experiment, the studio has “changed course.” Whatever the stated reason, the reality is that the concept is too risky to try. Making the girls as bad as the boys denies the sacred sin of toxic masculinity. Letting the girls succeed employs the despised feminine moral pedestal, laying all responsibility for social vice and virtue at the feet of women. Warner Brothers knew it couldn’t win on this one.

We’ve lost very little. Compared to an all-female Lord of the Flies, Baby Island offers a more authentic study of human nature in terms of sex. Its retrograde perspective, though, assures that if the book were to achieve a renaissance of interest, it would only be for the purpose of provoking outrage. We used to ban books like To Kill a Mockingbird and, verily, Lord of the Flies. Now little creativity is needed to imagine the reaction of a public-school ELA teacher or librarian who encountered a sentence like, “[Mary] was a motherly girl who was never so happy as when she had borrowed a baby to cuddle or care for.” Children must obviously be protected from such a dangerous text.

Brink’s characterization of Mary falls on contemporary ears as the epitome of antiquated, stifling stereotyping. This only demonstrates how narrow our own perspective has grown. Brink is better known for Caddie Woodlawn (1935), her answer to the acute uprightness of Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House books. Caddie, an eleven-year-old settling the American frontier with her family, gets in more trouble than Laura. Her dad is of the Catherine Beecher school of thought on physical activity for girls: after losing one sickly daughter, Mr. Woodlawn wants Caddie and her sisters to gain strength and resilience by getting dirty and rumpled outside. These ideas should make Brink a poster girl for the generic brand of feminism approved by the public.

The fact that Brink wrote both Caddie and Mary shows how options for women have contracted. Caddie and Mary are probably fleshed out in our minds as blocky representations of a certain type of female. Caddie is good: she tears around speaking truth to power. Mary is ungood: her whole personality is liking babies. We overlook the fact that Caddie’s adventuring drives her to acts of care, and Mary is utterly bold and fearless on behalf of her babies. We want our daughters to be strong Caddie, not mushy Mary. But to indulge in a bit more meta-fictional speculation, I bet Caddie would have done really well on an island with four babies, and Mary would have been a blessed help to a frontier household. Although the two characters have different native interests, they both possess the most needful attributes of a good man or woman: a prioritization of the needs of others, and the resourcefulness and energy to meet those needs.

This stands in contrast to knowledge held by anyone who has much contact with the humans now known as “tweens.” Such students of humanity would find Baby Island as unrealistic as Golding found The Coral Island. Requiring these children to choose their own sex is the righteous cause of society’s loudest zealots. One wonders how many of the zealots have spent enough time with eleven-year-olds to know their real capacity for life’s challenges, like making a meal (not a Lunchable) or showering daily. The idea that two middle school girls would be capable of caring for four babies on a beach was farfetched in 1937, but it wasn’t absurdist. Today’s American sixth grader would probably encounter the work more as a piece of science fiction than light fantasy.

Then again, it might do what science fiction does, and get her thinking—really thinking. Really imagining what it would be like to take care of herself, or, mirabile cogitatu! what it would be like to take care of that most alien creature, a baby. And that would be fantastic.