This essay is part of a week-long series drawn from the Witherspoon Institute’s project on Natural Law, Natural Rights, and American Constitutionalism. Click here to read PD Editor-in-Chief R.J. Snell’s introduction to the series.

Civil rights may be comprehensively defined as the rights to common or equal participation in civil society. Natural law governs the terms of participation in civil society, comprehensively extending from conception to full maturity. Accordingly, an accounting of civil rights calls for an accounting of natural law. Here we will define natural law, as it pertains to human action, as did C. S. Lewis: a standard of right conduct—not of humans’ own making—for beings whose self-directed motions are not determined by regularities of material bearing. That such a rule lies at the bottom of what are termed “civil rights” may not at first seem evident, particularly in the United States, where civil rights have had to be fought for and won through perseverance. That judgment would be mistaken, however, and we may readily discern the extent of that mistake by reviewing the development of our understanding of civil rights.

We define civil rights in the context of the founding of the United States Constitution, and in many respects they are best understood in that light. The first place in which to find that context is the Declaration of Independence, which declares the meaning of civil rights.[1] Secondly, we have the best indigenous articulation of civil rights from that founding father who also best explained the relation between civil rights and natural law: James Wilson. Thirdly, reviewing illustrative Supreme Court defenses of civil rights can quickly reveal how far the decisions of the justices were regulated so as to tie advances in civil rights to an advance in understanding natural law (even for persons who would disavow reliance upon natural law). Finally, the seminal statement of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” clearly expresses the fundamental ground of equality identified by James Wilson (and the Declaration of Independence) as essential to civil rights; it also invokes the entire sweep of Western reflection on the meaning of justice in such a way as to show the pursuit of civil rights as nothing less than perfecting civil relations in light of natural law.

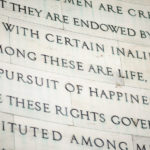

Someone may object that the Declaration of Independence establishes a defense of political rights and therefore not, as such, civil rights (often treated either as independent of, or as dependent upon or derivative from, political rights). Let us clarify, then: when the Declaration asserts that “to secure” the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,

governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, – That whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its power in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness,

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.

it most of all distinguishes the natural rights antecedent to every government and the resultant “civil rights” that restrain governments to observing and protecting those natural rights.

Such a reading is readily deducible from the elegant formulation of James Wilson, a member of the Constitutional Convention of the United States in 1787 and also a Justice on the first Supreme Court under the Constitution. Wilson provided that citizens, regardless of identity or culture, are entitled to “natural” and “acquired” rights, the latter consisting of two rights: the right to “the honest administration of the government in general,” and, “in particular, to the impartial administration of justice.”[2] Wilson was not alone in this assertion: he elaborated and confirmed strong suggestions contained in the Constitutional Convention and most notably in The Federalist Papers. The latter argues specifically that “justice is the end of government,” that, “security for civil rights must be the same as that for religious rights. . . ,”[3] and that civil rights concern the protections of all parties of the whole, minority or otherwise.[4]

Justice Wilson’s definition of civil rights went to the heart of the concept. He is most helpful, however, in articulating the foundations of that concept, which he accomplished in his law lectures on the topics of “natural rights,” “the general principles of law,” and “the law of nature.”

The discussion of natural rights begins from the universally accepted concept of a transition from a “state of nature” into a “state of civil society,” mediated by individuals surrendering some natural rights in order to attain civil security. However, Wilson insists, contradicting Edmund Burke and William Blackstone, that what is surrendered is minimal indeed because civil rights are founded on “the stable foundation of nature,” and not “the precarious and fluctuating basis of human institution.”[5]

The “Lectures on Law” discussed the general principles of law as progressing naturally and consistently from the law of God to man-made law. In that process, Wilson reasoned, man could place confidence in the project of protecting civil rights without surrendering a claim to justice. God’s law for man (apart from that communicated only in Revelation) “is communicated to us by reason and conscience.” Such law known purely by “reason and the moral sense” “has been called natural.” Furthermore, “[h]uman law,” which has “deficiencies,” “must rest its authority, ultimately, upon the authority of that law, which is divine.” Among the kinds of human law Wilson defines “[t]hat [law] which a political society makes for itself” as “municipal law.”[6]

Wilson’s “municipal” law is the primary focus of concerns for civil rights because of a second important argument of his: namely, civil rights originate in concerns for domestic economy or household management, (or in other words, marriage, parentage, and character formation), because it is precisely in that environment that citizens are brought to full maturity, fit for the common or equal enjoyment of and responsibility for the order of civil society.

Wilson reiterates: since government itself results from the natural law, every government that fails to secure and enlarge the exercise of natural rights “is not a government of the legitimate kind.” Natural law in that sense points to the obligations of humans as they stand “unrelated” to others, “related” to particular others, and “related” to others in general. Insofar as humans stand unrelated (“state of nature”) there is no role for government; insofar as they stand in either particular or general relations, government plays the role of securing their rights and responsibilities in those relationships. In general (“in his unrelated state”) man has natural rights to property, his character, liberty, and safety. In his “peculiar relations,” depending on whether he is a spouse, parent, or progeny, he has “peculiar rights” and “peculiar duties.” In his “general relations” man has the rights “to be free from injury, and to receive the fulfillment of the engagements, which are made to him” and the duties “to do no injury, and to fulfill the engagements, which he has made.”[7]

The paramount universal duty of government is the duty to “preserve human life.” Reviewing the history of the exercise of unnatural powers over the “newly born,” Wilson recognizes the “consistency, beautiful and undeviating,” with which the “common law” “protects human life, from its commencement to its close.” This common law is the same discovered by Sir Edward Coke in Euripides (“the common law of Athens”) and thus appropriated by Wilson as a standard imperfectly attained until the most recent times.

In the contemplation of law, life begins when the infant is first able to stir in the womb. By the law, life is protected not only from immediate destruction, but from every degree of actual violence, and, in some cases, from every degree of danger.[8]

In other words, the rights attaching to man in “his unrelated state” (merely by virtue of his humanity), subsequently obligate government and, indeed, provide initial legitimacy to government. Next Wilson took up in sequence marriage (“the true origin of society”), parentage (“the relation of parent and child”), and “the duty of parents to maintain their children decently; . . . to protect them, . . . and to educate them. . . .” He also ruled out slavery as “unauthorized by the common law. Indeed, it is repugnant to the principles of natural law, that such a state should subsist in any social system.”[9]

What this account means is that the best understanding of civil rights in practice is derivable from close attention to how citizens in any given country—indeed persons altogether—are treated in the course of the conduct of their lives in their ordinary relations. As Wilson put it, “publick law and publick government were not made for themselves,” but for “society” . . . “particularly domestick society.”[10]

It is therefore notable that many of the landmark decisions concerning civil rights in the United States touch upon precisely the monuments of domestic economy cited by James Wilson.

The United States Supreme Court has upheld individual rights of marriage not merely as a positive result of the prescriptions of the Constitution or statutes but as something “long recognized” as one of “the vital personal rights essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men.” Moreover, “marriage is one of the ‘basic civil rights of man,’ fundamental to our very existence and survival.”[11] Similarly, the freedom of contract and the right to maintain a home for a family were affirmed on the grounds that the “rights to acquire, enjoy, own and dispose of property . . . [were] . . . an essential pre-condition to the realization of other basic civil rights and liberties. . . .”[12] Finally, the rights of parents to educate their children not only have been held not to derive from positive law but have been deemed strong enough to resist even the demands of positive law. To quote the Court,

The fundamental theory of liberty upon which all governments in this Union repose excludes any general power of the State to standardize its children by forcing them to accept instruction from public teachers only. The child is not the mere creature of the State; those who nurture him and direct his destiny have the right, coupled with the high duty, to recognize and prepare him for additional obligations.[13]

These judicial affirmations of natural law dramatically confirm the analyses of C. S. Lewis and Justice Wilson. That is to say, arguments from “fundamental theory” are far more the reasons for those decisions than any compulsive operation of the laws. To that extent, they reflect the force of natural law thinking in lighting the path to civil rights. It is perhaps ironic, therefore, that the most fundamental, initiating right to life itself, in light of which the rights of domestic economy gain traction, has received from the Supreme Court only the blessing of positive prescription and been qualified by subjection to the countervailing will of others.

If anything were to reveal the necessity to found civil rights on altogether “fundamental” and “unqualified” arguments, it would surely be the ultimate defense of civil rights penned by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. He stated at the outset that “I am in Birmingham because injustice is here,” which means that he took a transcendent standard and not a transient promise as the basis of the claims he defended. He argued for the “interrelatedness of all communities and states,” which in turn led him to the famous formulation, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” In short, King believed that the defense of civil rights for black people in particular required the articulation of the rights of people anywhere and everywhere.

King manifested this perspective in his defense of civil disobedience:

Since we so diligently urge people to obey the Supreme Court’s decision of 1954 outlawing segregation in the public schools, at first glance it may seem rather paradoxical for us consciously to break laws. One may ask: “How can you advocate breaking some laws and obeying others?” The answer lies in the fact that there are two types of laws: just and unjust. I would be the first to advocate obeying just laws. One has not only a legal but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws. I would agree with St. Augustine that “an unjust law is no law at all.”[14]

It was on the foundation of St. Augustine’s natural law theory, then, that King discovered the grounds of civil disobedience: “A just law is a man-made code that squares with the moral law or the law of God. An unjust law is a code that is out of Harmony with the moral law.” Nor did he stop there. He invoked Aquinas, Martin Buber, Socrates, Tillich, and Niebuhr (among other authorities) to establish that the claim he defended was not a parochial claim merely derived from majority rule.

To defend civil rights for black people meant to prove that “segregation is not only politically, economically and sociologically unsound, it is morally wrong and sinful.” The moral error begins with the denial of common or equal position in the civil society, and it ends with refusing to some “the honest administration of the government and the impartial administration of justice.” Thus, the examples King used covered the same two categories established by Justice Wilson.

First, he cited the “code that a numerical or power majority group compels a minority group to obey but does not make binding on itself.” This, he held, is “difference made legal,” where the term difference means precisely unjust. The rule of justice is “sameness made legal.” To attain that standard of governmental performance, however, requires common and equal participation in the civil society and in the government predicated upon that society. Thus, people should not be subject to laws which they “had no part in enacting or devising.”

The second category, the impartial administration of justice, provided the most dramatic defense of the theory King defended, for in mounting the argument against the “racial injustice [that] engulfs this community,” King had to bring his case home to the level of domestic economy that revealed precisely how far civil rights had been impaired. The reductio ad absurdum of lunch counter sit-ins to defend the right to enjoy public custom was not meant to show how trivial civil rights claims were but rather how far injustice had penetrated. What was amiss was the ability of American blacks to conduct themselves under the guidance of natural law because of the unnatural (preternatural?) obstruction of their opportunities to do so. That meant no families, properly speaking; no education, properly speaking; no self-government, literally speaking. Where there is no domestic economy there is no political community.[15]

If it is warrantable to insist that all human beings should live in accord with the law of nature, then it is an absolute requirement that all be secured the civil opportunity to do so. For that reason, civil rights can be meaningfully defined only as the common or equal participation in civil society.