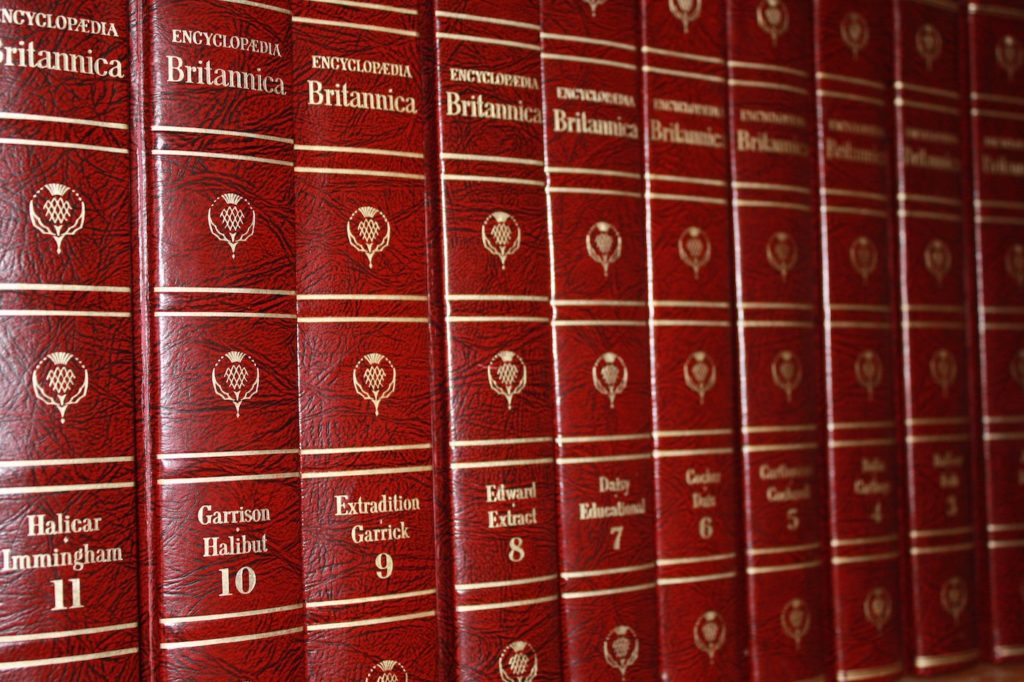

As far back as I can remember, my childhood home had an Encyclopedia Britannica, a late 1950s revision of its fourteenth edition, which came in its own wooden two-shelf bookcase, with a deep slot in the back that held a massive atlas. My siblings and I all used it when working on our homework, and it was a ready resource for idle browsing when one was bored or hadn’t decided what book to read next.

I suppose Britannica began my fondness for reference books—that and the Random House Dictionary my parents bought when it came out in 1966. I now have that dictionary, though the Britannica I rather sorrowfully let go after my parents passed away. In my home office today, I have one bookcase mostly filled with reference books of various descriptions—on language, history, philosophy, religion, law, and politics.

Why bother with the books? Can’t we just look up everything online nowadays, thanks to Google and Wikipedia? Not really—or perhaps not just yet—in part thanks to copyrights and paywalls. Google and other search engines often yield bizarre results, requiring the exercise of some prior knowledge and judgment to tell the wheat from the chaff. And Wikipedia, which I use frequently, is difficult to trust on anything beyond bare facts (and even those are sometimes wrong). If you want to know the date of the battle of Blenheim, fine. But if you want a reliable understanding of the War of the Spanish Succession of which it was a part, not so much. For that I would turn to the brief entry in George C. Kohn’s Dictionary of Wars. For non-paywalled online resources on specific subjects, the one that comes most readily to mind for exceeding its print rivals in expertise and comprehensiveness is the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. But in general I still find reference books hard to beat.

Why bother with the books? Can’t we just look up everything online nowadays, thanks to Google and Wikipedia?

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.The grandest of all references in our language is undoubtedly the Oxford English Dictionary. Having given my compact one-volume second edition (with its magnifying glass) to a young editor years ago, I use the continually updated online version, to which I am fortunate to have a university’s subscription access. The OED is really indispensable for writers and editors, and is unparalleled among English dictionaries for the etymology and evolving use of an increasingly global language.

For every editor, and for every writer who doesn’t want editors breathing down his neck, good usage guides are a must. The granddaddy of them all is H. W. Fowler’s A Dictionary of Modern English Usage, originally published in 1926. Fowler’s MEU has been updated by successive editors, not with altogether happy results, because the inimitable voice of Fowler—smart, acerbic, archly judgmental—has gradually gone quiet in the later editions. So I’m grateful that Oxford keeps a paperback of the first edition in print. That’s the one I’ve given to friends.

Fowler is browsable, idiosyncratic, and fun to read. But he is not right about everything—that is, in some cases he was right in his day but is not so right now, because usage evolves. For everyday reliability, the best current reference is Garner’s Modern English Usage by Bryan A. Garner, now in its fourth edition, and also available as a smartphone or tablet application. Garner has sound judgment about grammar, meaning, and style, and his entries are historically informed about the constant changes English undergoes.

Oxford University Press—publisher of the OED, Fowler, and Garner—is easily the leading English language publisher of reference works, with Cambridge University Press close behind. My shelves hold Oxford’s Classical Dictionary, Dictionary of the Christian Church, dictionaries of Phrase and Fable and Allusions, Companions to U.S. History, Law, and the Supreme Court, and more besides these. Each has its idiosyncrasies of selection and interpretation—I particularly recall using the Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court in my research years ago, and finding some real bloopers in it—but in general I find such books more dependable than Wikipedia or other online sources.

For every editor, and for every writer who doesn’t want editors breathing down his neck, good usage guides are a must.

In the not-quite-a-reference category is a book published originally as a textbook that I use as a reference: The Trivium, by Sister Miriam Joseph Rauh, who taught for many years at Saint Mary’s College in South Bend (in the days when it was the women’s counterpart to the all-male Notre Dame). Subtitled The Liberal Arts of Logic, Grammar, and Rhetoric: Understanding the Nature and Function of Language and reprinted in recent years by Paul Dry Books, Sister Miriam’s precisely constructed tour of the classical trivium is my go-to resource for pinning down logical fallacies and rhetorical misconstructions. (Paul Dry also republished her Shakespeare’s Use of the Arts of Language, a book of remarkable range and detail demonstrating a complete mastery of the Bard’s works. It must have been a real blessing to have been one of Sister Miriam’s students.)

As with many other kinds of books, I’ve found some of the most interesting references in my collection in used bookstores. One such is A Dictionary of Americanisms on Historical Principles, first published by the University of Chicago Press in 1951. This work does OED-worthy etymology and history of peculiarly American colloquialisms, ranging across agricultural terms, flora and fauna, folk expressions, regionalisms, material culture, Native American derivations, and social, civic, and religious expressions. If you come across a historical or literary reference to a “Jenny Lind carriage,” there’s a picture of one here. It makes for delightful browsing.

So too does The Sailor’s Lexicon, by Admiral W. H. Smyth of the Royal Navy, published in the mid-nineteenth century. I’m sure I read somewhere once that Patrick O’Brian relied on Smyth when writing his Aubrey-Maturin novels of naval warfare in the Napoleonic age. If, like Dr. Maturin, you cannot recall what it means to have the weather-gage, Smyth will tell you.

For my own research into the development of American constitutional law, one of my most useful finds years ago was the Cyclopedia of American Government, edited by Andrew C. McLaughlin and Albert Bushnell Hart and published in 1914 (my copy is a 1963 reprint). This is a three-volume work of more than 2,000 pages, for which McLaughlin and Hart (themselves leading scholars in that period) recruited the cream of the American academy to write the individual entries, and its ambitious scope means that it is a finely detailed snapshot of contemporaneous political life and historical understanding a little over a century ago. What others might dismiss as an obsolete compendium of outdated information is for me an important historical record.

When I was trying to hunt down the origins of the expression “judicial review” as a reference to the judiciary’s power to invalidate legislation on constitutional grounds, it was fascinating to prowl through this authoritative-for-its-time reference book and find not only that there was no entry with that title, but also no use of the term in any other entry where it might be expected to appear. This was the very same year that Princeton’s Edward S. Corwin (one of the contributors to the Cyclopedia) published The Doctrine of Judicial Review, so it was quite a revelation to discover how fresh and new the phrase was at this time—something I was able to make much of when I published a critical introduction to a new edition of Corwin’s book on its hundredth birthday.

From the whimsical to the obscure to the most dry-as-dust earnestness, reference books represent our impulse—perhaps our need—to organize the world around us, and even the worlds inside our heads, into some form of order and sharper understanding. Since I first cracked open that Britannica as a kid, they have drawn me in and filled me with gratitude.