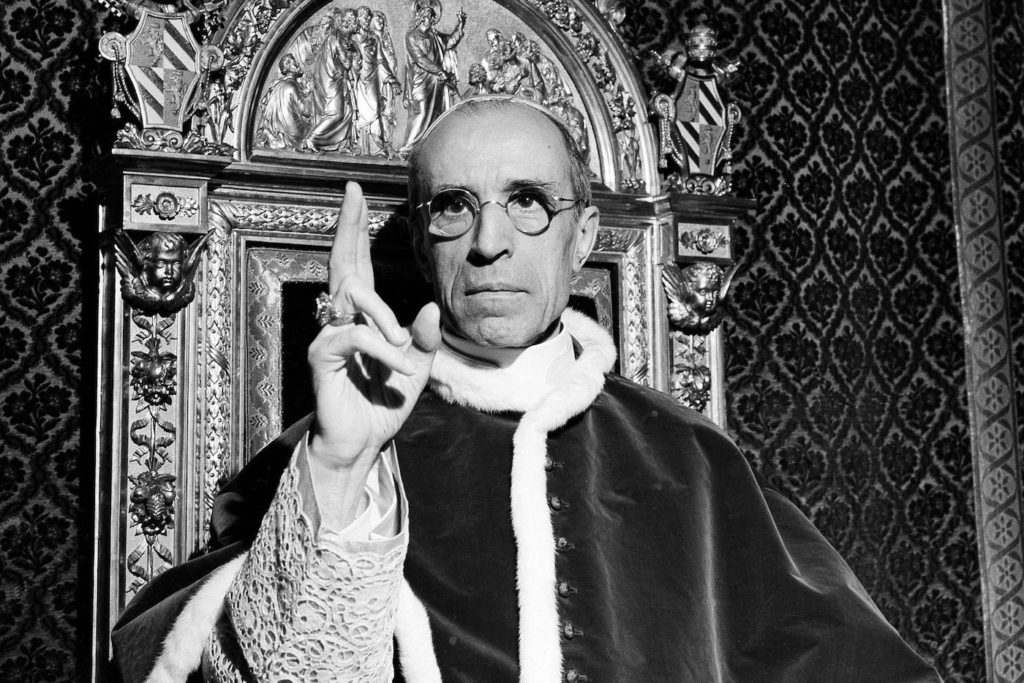

The legacy of Pius XII, the pope at the helm of the Catholic Church during World War II, has been surrounded by controversy for decades. After the war, his leadership record became embroiled in debate: were his efforts to aid Holocaust victims sufficient? Or did he maintain “holy silence” about the wickedness perpetrated by the Nazis? The controversy first drew significant attention in the 1960s, when the Kremlin put its anti-Christian disinformation campaign into full gear, focusing on the recently deceased pope and supposedly cataloguing his failings during the Second World War.

To get to the truth, Pius XII’s successor, Pope Paul VI, tasked four Jesuit priests with culling through Vatican archives to find documents focusing on the Holy See and the war. They put together an eleven-volume set of books, known as the Actes et Documents du Saint Siège relatifs à la Seconde Guerre Mondiale (“Actes et Documents”).

Unfortunately, that effort failed to quell the debate, so in 2020 the Vatican opened previously sealed archives containing about sixteen million pages of primary documents, in the hope of resolving unanswered questions. I obtained the credentials, permissions, and funding to work in Rome that summer of 2020, but Covid-19 closed the archives and delayed my research plans.

Brown University’s David Kertzer’s timing was better. He and his team got in early, for just a short time prior to the closing, and he returned as soon as it was possible after the reopening. This archival research eventually produced his new book, The Pope at War: The Secret History of Pius XII, Mussolini, and Hitler.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Unfortunately, Kertzer’s book is agenda-driven and makes several factual errors. The author fails to take stock of recent scholarly contributions on Pius’s record and ends up misrepresenting or entirely omitting key information.

There are at least seven books on Pius XII with publication dates of 2020 or later. Books by Johan Ickx (Le Bureau. Les Juifs de Pie XII, 2020), Michael Hesemann (The Pope and the Holocaust: Pius XII and the Secret Vatican Archives, 2022), Christian Jennings (Syndrome K: How Italy Resisted the Final Solution, 2022), Gazegoraz Górny and Janusz Rosikon (Vatican Secret Archives, 2020), Cesare Catananti (Il Vaticano nella Tormenta, 2020) and Patrick Gallo (The Nazis, the Vatican, and the Jews of Rome, forthcoming), and all give positive reviews of Pius XII’s wartime leadership. Only David Kertzer claims to have found damning evidence in the archives.

After the book was in print, I went to my local bookstore and bought a copy. The first thing I did was check the bibliography. There were no listings for Mark Riebling, Ion Pacepa, myself, or any of the new Pius XII books noted above. So, I knew that Kertzer was not addressing the most important recent developments in the Pius XII debate, especially the pope’s role in plots to assassinate Hitler and the Kremlin’s disinformation campaign against him. By avoiding those issues, Kertzer disqualified his book from being what he claimed it was: a “full account” of Pius XII’s “actions during the war, and why and how . . . he made the fraught decisions he did.”

New Findings?

What Kertzer calls his “most shocking finding” is that within weeks of Pius XII’s 1939 coronation, Hitler sent Prince Philip of Hesse to negotiate an agreement with the Vatican. Kertzer says of the negotiations, “we didn’t know about these until just now.” In fact, on page 58, he accuses the Jesuit editors of the Actes et Documents of having “systematically expunged all reference” to the talks.

Kertzer is simply wrong. The talks are neither a new revelation nor in any way shocking. Negotiations were proposed by Germany well before the death camps were in place. No one knew how Nazi persecution would evolve, and the pope had an opportunity and an obligation to protect the rights and lives of people under his charge. So he agreed to the meetings. I note as an aside that the Church’s massive humanitarian efforts could never have taken place if he had refused negotiations and left Church properties unprotected in Nazi territories.

Furthermore, the editors of Actes et Documents certainly did not “systematically expunge” all reference to communications between the prince and Pius. One can find multiple references to their negotiations in the volumes. Document 254 in the first volume of Actes et Documents is a note stating that “the Prince of Hesse” was involved in secret preparations for a meeting between German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop and the pope. The first footnote to the text, added by the Jesuit editors, reads: “Prince Philip of Hesse . . . acted frequently as an intermediary between Berlin and Rome” and noted that he “evidently had many secret audiences with Pius XII.”

The Vatican published that first edition of the Actes et Documents in 1965. It also put the document and the explanatory footnote on the Vatican webpage in March 2010, along with the rest of the collection. In fact, the introduction to the second volume of the Actes et Documents (pages 20–21), written by the Jesuit editors, highlights communications between Germany and the new pontiff, including a note about a visit from the German ambassador just three days after Pius XII became pope.

That passage goes on to refer to a letter from the pope to Hitler. Kertzer discusses that letter as though he were the first to discover it. He writes, “After welcoming [German envoy] von Hessen, the pope took out a copy of the letter he had sent Hitler shortly after his election as pope two months earlier. He read it aloud to the prince, then read Hitler’s reply.” Kertzer does not, however, mention that the full letter was published in volume II of the Actes et Documents (page 420) or that it was put on the Vatican webpage in 2010.

This letter, like the meeting itself, was part of an appeal that Germany reverse its course and avoid catastrophic bloodshed. The point here, though, is that if the editors wanted to erase all evidence of contact between the pope and Hitler, they would never have published this letter, which is more direct contact than any meeting with an intermediary. Nor would the Vatican have put it online. Moreover, although Kertzer begins by implying that the negotiations would end up in a shameful capitulation by the pope, nothing came of them. Kertzer ultimately admits that “[i]n the end, no formal agreement emerged. . . .”

Outdated and Incorrect Sources

Some of Kertzer’s errors are rather surprising. The final paragraph in chapter eight suggests that Pius assured Hitler he would not respond to Nazi abuses. The footnote does not lead to a new archival document but rather to a note saying that this was “quoted by” Saul Friedländer in his 1966 book. Friedländer, however, eventually changed his views on the pope’s WWII record. By 2010, after decades of research, Friedländer was defending Pius XII, noting the pope’s aversion to Nazism and saluting his collaboration in writing Pope Pius XI’s anti-Nazi encyclical, Mit brennender Sorge.

Kertzer, on the other hand, claims that “Cardinal Pacelli [Pius XII], worried about antagonizing the Führer, advised against [publication of Mit brennender Sorge].” Kertzer offers no citation for this claim, and he’s simply wrong; that encyclical was Pacelli’s project. The archives make clear that he, the future Pope Pius XII, personally strengthened the encyclical’s language, even changing the title from “With Great Concern,” to “With Burning Anxiety.”

Kertzer repeats an old canard that Pius was racist because a British memorandum from after the liberation of Rome says the pope requested that “colored troops” not be used to garrison the Vatican. This issue stems from a report Pius received about specific French Moroccan troops. They were particularly brutal to Roman citizens. The pope did not want those soldiers stationed in Rome (or anywhere else). He expressed his concerns to British envoy D’Arcy Osborne, who broadened the statement in his cable back to London, saying that the pope did not want “colored troops” stationed at the Vatican. That the pope’s concern was about specific French Moroccan troops was made clear in a declassified confidential memorandum from the OSS, an article that appeared in the Vatican newspaper, and a message sent from the Vatican to its representative in France. None of those documents made reference to race, just the pope’s concern over those particular troops.

Soon after the new archives were opened, researcher Fr. Hubert Wolf raised questions based on his initial findings. Wolf suggested that the Vatican withheld information about the Holocaust from the Allies. Kertzer repeated those arguments in chapter twenty-three. Like Friedländer, however, Wolf changed his mind after doing more work. He discovered that the Holy See regularly responded to Jewish calls for help, with “money, food or shelter” and that the pope assisted Jews in obtaining visas to escape Nazi deportation. These later, more accurate findings contradict Kertzer’s thesis, so he ignored them.

Kertzer finds fault with Pius XII’s response to the Nazi roundup of Roman Jews on October 16, 1943. He argues that the deportations did not sufficiently concern the pope because he met with British envoy Osborne “on the day the Jews were being forced onto the train in Rome,” but he supposedly failed to mention the deportations. Moreover, when he received the American envoy Harrold Tittmann “the next day,” he again failed to mention the Jews. Once more, Kertzer is simply wrong.

What we do know about Pius, but not from Kertzer, is that he collaborated with those officers of the Wehrmacht who wanted to overthrow Hitler.

British archives show that Osborne reported to his government on the Vatican’s response: “As soon as he heard of the arrests of Jews in Rome, Cardinal Secretary of State sent for the German Ambassador and formulated some protest.” Slovakian representative Karol Sidor, whom the pope had also received, said, “On the orders of the Holy Father, more than a hundred Jews were . . . hidden in the Generalate of the Jesuits. Similarly, Jews and their entire families were hidden in every monastery.” It is true, however, that Tittmann did not mention the roundup in his report, dated October 19.

As has been known for at least two decades (I first wrote about it in the 2000 edition of Hitler, the War, and the Pope), the October 19 date on the memo is wrong. Other records conclusively establish that the meeting took place on October 14. Thus, the pope could not have spoken about the October 16 roundup; it hadn’t taken place. If Kertzer had done his work properly, he never would have made that mistake.

Kertzer acknowledges that the archives have no “smoking gun,” and he admits that “Pius XII and Adolf Hitler had no affection for each other.” Still, he charges the wartime pontiff with callous disregard for Jewish suffering. Of course, he reached that conclusion long before he looked in the archives. In 2011, Kertzer told the Associated Press that Pius XII was a “moral coward,” and in a series of books across his career he has charged popes of different eras with abusing Jews. That attitude leads him to make truly unfair charges—for example, suggesting that Pius XII’s effort to prevent the war was merely an ambition-driven effort to fulfill his “dream of playing peacemaker.”

Unfair Portrait

At the end of the day, there is some new information in this book, but the author is so unfair that one has a hard time distilling the truth from the bias.

What we do know about Pius, but not from Kertzer, is that he collaborated with those officers of the Wehrmacht who wanted to overthrow Hitler. They approached the pope and asked him to negotiate an armistice with the Allies if they succeeded. We also know that Pius informed the British about this conspiracy and that he notified the Allies in advance about Hitler’s planned invasion of the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg. We also know that he sent open telegrams commiserating with the overrun nations. We know that he was regularly informed about plans to assassinate Hitler and that the conspirators used his blessing to gain new support for their efforts. We also know of numerous tributes and offers of thanks that were given by Jewish individuals and groups to Pius both after the war and at the time of his death.

In June 2022, the Historical Archives of the Second Section of the Vatican Secretariat of State placed online documents relating to 2,700 requests from persecuted Jews for help from the Holy See. These archives confirm the long-standing testimony of witnesses to the tireless efforts of Pius XII and his offices to help people in need regardless of faith. Through more than forty papal interventions, hundreds of thousands of Jews were saved from the death camps. In about 25,000 cases, the Holy See helped Jews escape from Nazi-occupied territories. These diplomatic efforts appear nowhere in The Pope at War. Only with such omissions can Kertzer maintain the argument that Pius XII was indifferent to the fate of the Jews.