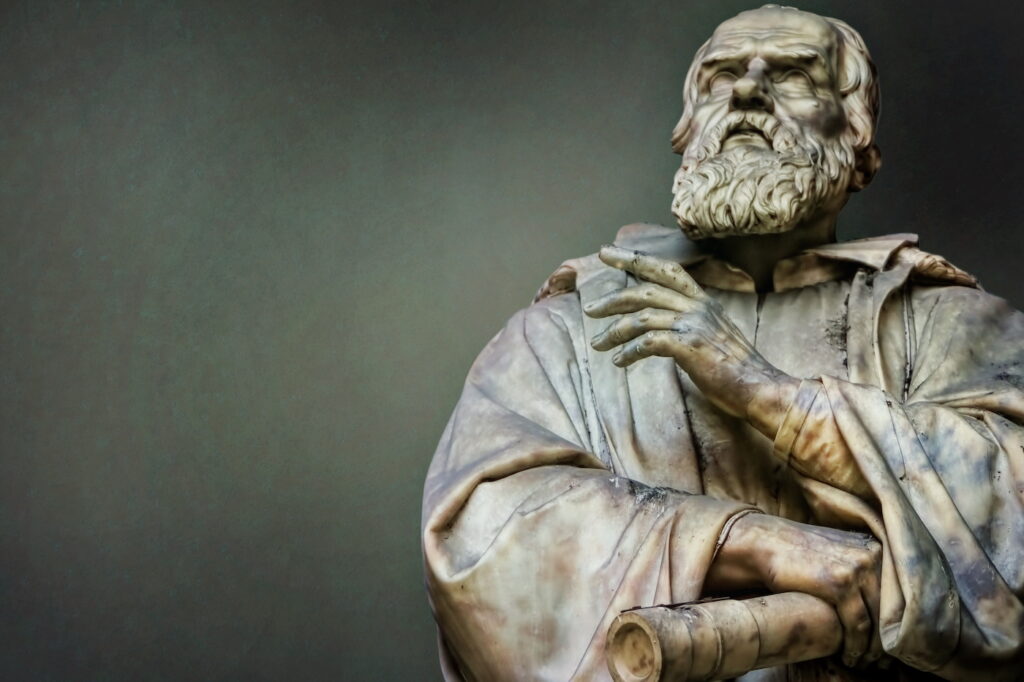

There are few images of the modern world more powerful than that of the humbled Galileo, kneeling before the cardinals of the Holy Roman and Universal Inquisition, being forced to admit that the Earth did not move. The story is familiar: that Galileo represents science fighting to free itself from the clutches of blind faith, biblical literalism, and superstition. The story has fascinated generations, from the philosophes of the Enlightenment to scholars and politicians in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The specter of the Catholic Church’s condemnation of Galileo continues to influence the modern world’s understanding of the relationship between religion and science. In October 1992, Pope John Paul II appeared before the Pontifical Academy of the Sciences to accept formally the findings of a commission tasked with historical, scientific, and theological inquiry into the Inquisition’s treatment of Galileo. The Pope noted that the theologians of the Inquisition who condemned Galileo failed to distinguish properly between particular biblical interpretations and questions pertaining to scientific investigation.

The Pope also observed that one of the unfortunate consequences of Galileo’s condemnation was that it has been used to reinforce the myth of an incompatibility between faith and science. That such a myth is alive and well was immediately apparent in the way the American press described the event in the Vatican. The headline on the front page of The New York Times was representative: “After 350 Years, Vatican Says Galileo Was Right: It Moves.” Other newspapers, as well as radio and television networks, repeated essentially the same claim.

The New York Times story is an excellent example of the persistence and power of the myths surrounding the Galileo affair. The newspaper claimed that the Pope’s address would “rectify one of the Church’s most infamous wrongs—the persecution of the Italian astronomer and physicist for proving the Earth moves about the Sun.” For some, the story of Galileo serves as evidence for the view that the Church has been hostile to science, and the view that the Church once taught what it now denies, namely, that the Earth does not move. Some take it as evidence that teachings of the Church on matters of sexual morality or of women’s ordination to the priesthood are, in principle, changeable. The “reformability” of such teachings is, thus, the real lesson of the “Galileo Affair.”

But modern treatments of the affair not only miss key context surrounding the Inquisition’s condemnation of Galileo; they also misinterpret what the Catholic Church has always taught about faith, science, and their fundamental complementarity.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.For some, the story of Galileo serves as evidence for the view that the Church has been hostile to science, and the view that the Church once taught what it now denies, namely, that the Earth does not move.

Galileo and the Inquisition in the Seventeenth Century

Galileo’s telescopic observations convinced him that Copernicus was correct. In 1610, Galileo’s first astronomical treatise, The Starry Messenger, reported his discoveries that the Milky Way consists of innumerable stars, that the moon has mountains, and that Jupiter has four satellites. Subsequently, he discovered the phases of Venus and spots on the surface of the sun. He named the moons of Jupiter the “Medicean Stars” and was rewarded by Cosimo de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, with appointment as chief mathematician and philosopher at the Duke’s court in Florence. Galileo relied on these telescopic discoveries, and arguments derived from them, to bolster public defense of Copernicus’s thesis that the Earth and the other planets revolve about the sun.

When we speak of Galileo’s defense of the thesis that the Earth moves, we must be especially careful to distinguish between arguments in favor of a position and arguments that prove a position to be true. Despite the claims of The New York Times, Galileo did not prove that the Earth moves about the sun. In fact, Galileo and the theologians of the Inquisition alike accepted the prevailing Aristotelian ideal of scientific demonstration, which required that science be sure and certain knowledge, different in some ways from what we today accept as scientific. Furthermore, to refute the geocentric astronomy of Ptolemy and Aristotle is not the same as to demonstrate that the Earth moves. Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe (1546–1601), for example, had created another account of the heavens. He argued that all the planets revolved about the sun, which itself revolved about a stationary Earth. In fact, Galileo himself did not think that his astronomical observations provided sufficient evidence to prove that the Earth moves, although he did think that they called Ptolemaic geocentric astronomy into question. Galileo hoped eventually to argue from the fact of ocean tides to the double motion of the Earth as the only possible cause, but he did not succeed.

When we speak of Galileo’s defense of the thesis that the Earth moves, we must be especially careful to distinguish between arguments in favor of a position and arguments that prove a position to be true.

Cardinal Robert Bellarmine, Jesuit theologian and member of the Inquisition, told Galileo in 1615 that if there were a true demonstration for the motion of the Earth, then the Church would have to abandon its traditional reading of those passages in the Bible that appeared to be contrary. But in the absence of such a demonstration (and especially in the midst of the controversies of the Protestant Reformation), the Cardinal urged prudence: treat Copernican astronomy simply as a hypothetical model that accounts for the observed phenomena. It was not Church doctrine that the Earth did not move. If the Cardinal had thought that the immobility of the Earth were a matter of faith, he could not argue, as he did, that it might be possible to demonstrate that the Earth does move.

The theologians of the Inquisition and Galileo adhered to the ancient Catholic principle that, since God is the author of all truth, the truths of science and the truths of revelation cannot contradict one another. In 1616, when the Inquisition ordered Galileo not to hold or to defend Copernican astronomy, there was no demonstration for the motion of the Earth. Galileo expected that there would be such a demonstration; the theologians did not. It seemed obvious to the theologians in Rome that the Earth did not move and, since the Bible does not contradict the truths of nature, the theologians concluded that the Bible also affirms that the Earth does not move. The Inquisition was concerned that the new astronomy seemed to threaten the truth of Scripture and the authority of the Catholic Church to be its authentic interpreter.

The Inquisition did not think that it was requiring Galileo to choose between faith and science. Nor, in the absence of scientific knowledge for the motion of the Earth, would Galileo have thought that he was being asked to make such a choice. Again, both Galileo and the Inquisition thought that science was absolutely certain knowledge, guaranteed by rigorous demonstrations. Being convinced that the Earth moves is different from knowing that it moves.

The disciplinary decree of the Inquisition was unwise and imprudent. But the Inquisition was subordinating scriptural interpretation to a scientific theory, geocentric cosmology, that would eventually be rejected. Subjecting scriptural interpretation to scientific theory is just the opposite of the subjection of science to religious faith!

In 1632, Galileo published his Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, in which he supported the Copernican “world system.” As a result, Galileo was charged with disobeying the 1616 injunction not to defend Copernican astronomy. The Inquisition’s injunction, however ill‑advised, only makes sense if we recognize that the Inquisition saw no possibility of a conflict between science and religion, both properly understood. Thus, in 1633, the Inquisition, to ensure Galileo’s obedience, required that he publicly and formally affirm that the Earth does not move. Galileo, however reluctantly, acquiesced.

From beginning to end, the Inquisition’s actions were disciplinary, not dogmatic, although they were based on the erroneous notion that it was heretical to claim that the Earth moves. Erroneous notions remain only notions; opinions of theologians are not the same as Christian doctrine. The error the Church made in dealing with Galileo was an error in judgment. The Inquisition was wrong to discipline Galileo, but discipline is not dogma.

The Inquisition did not think that it was requiring Galileo to choose between faith and science. Nor, in the absence of scientific knowledge for the motion of the Earth, would Galileo have thought that he was being asked to make such a choice.

The Development of the Legend of Galileo

The mythic view of the Galileo affair as a central chapter in the warfare between science and religion became prominent during debates in the late nineteenth century over Darwin’s theory of evolution. In the United States, Andrew Dickson White’s History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom (1896) enshrined what has become a historical orthodoxy difficult to dislodge. White used Galileo’s “persecution” as an ideological tool in his attack on the religious opponents of evolution. Since it was so obvious by the late nineteenth century that Galileo was right, it was useful to see him as the great champion of science against the forces of dogmatic religion. The supporters of evolution were seen as nineteenth-century Galileos; the opponents of evolution were seen as modern inquisitors. The Galileo affair was also used to oppose claims about papal infallibility, formally affirmed by the First Vatican Council in 1870. As White observed: had not two popes (Paul V in 1616 and Urban VIII in 1633) officially declared that the Earth does not move?

The persistence of the legend of Galileo, and of the image of “warfare” between science and religion, has played a central role in the modern world’s understanding of what it means to be modern. Even today the legend of Galileo serves as an ideological weapon in debates about the relationship between science and religion. It is precisely because the legend has been such an effective weapon that it has persisted.

Galileo and the Inquisition shared common first principles about the nature of scientific truth and the complementarity between science and religion.

For example, a discussion in bioethics from several years ago drew on the myths of the Galileo affair. In March 1987, when the Catholic Church published condemnations of in vitro fertilization, surrogate motherhood, and fetal experimentation, there appeared a page of cartoons in one of Rome’s major newspapers, La Repubblica, with the headline: ‘In Vitro Veritas.’ In one of the cartoons, two bishops are standing next to a telescope, and in the distant night sky, in addition to Saturn and the Moon, there are dozens of test-tubes. One bishop turns to the other, who is in front of the telescope, and asks: “This time what should we do? Should we look or not?” The historical reference to Galileo was clear.

In fact, at a press conference at the Vatican, then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger was asked whether he thought the Church’s response to the new biology would not result in another “Galileo affair.” The Cardinal smiled, perhaps realizing the persistent power—at least in the popular imagination—of the story of Galileo’s encounter with the Inquisition more than 350 years before. The Vatican office that Cardinal Ratzinger was then the head of, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, is the direct successor to the Holy Roman and Universal Inquisition into Heretical Depravity.

There is no evidence that in 1633 when Galileo acceded to the Inquisition’s demand that he formally renounce the view that the Earth moves, he muttered under his breath, eppur si muove, “but still it moves.” What continues to move, despite evidence to the contrary, is the legend that Galileo represents reason and science in conflict with faith and religion. Galileo and the Inquisition shared common first principles about the nature of scientific truth and the complementarity between science and religion. In the absence of scientific knowledge, at least as understood by both the Inquisition and Galileo, that the Earth moves, Galileo was required to affirm that it did not. However unwise it was to insist on such a requirement, the Inquisition did not ask Galileo to choose between science and faith.