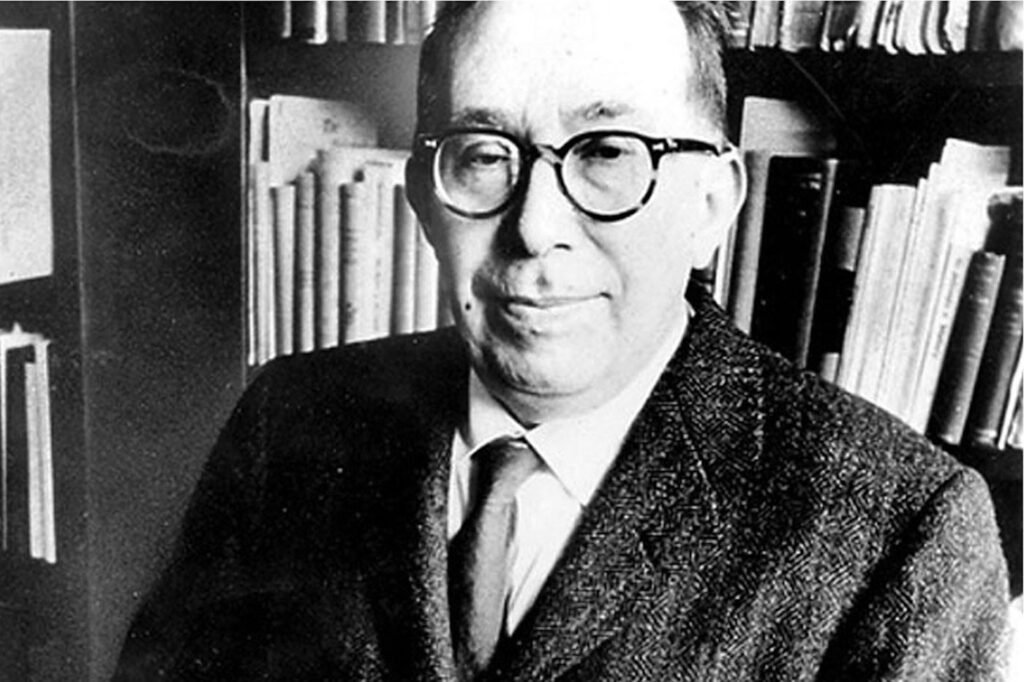

This essay is part of Public Discourse’s Who’s Who series, which introduces and critically engages with important thinkers who are often referenced in political and cultural debates, but whose ideas might not be widely known or understood. The series previously considered the life and work of Hannah Arendt, Antonio Gramsci, Jacques Maritain, Michael Oakeshott, Charles De Koninck, and Harry V. Jaffa and Allan Bloom.

Readers of this series should take special interest in the thought of Leo Strauss. Whereas most political thinkers devote themselves to developing a set of political theories, Strauss took the radical turn of investigating the possibility of political knowledge or political science generally, and whether such knowledge could ever rise to wisdom.

Situating these questions along the path of his thinking over his whole life is an important task, to which, unfortunately, we cannot possibly do justice here. We can nevertheless offer a shorter path that might guide those who seek political knowledge, perhaps even political wisdom, out of a concern for our current political situation. Such readers—curious but skeptical, worried yet hopeful—will find in Strauss surer guidance for these sentiments than anywhere else.

Positivism and Historicism

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Strauss often accused his discipline, political science, of a serious dereliction of duty, a failure to address the spiritual crisis the West faced from within and the political crisis it faced from Communism in the East. Notoriously, Strauss charged the new political science with “fiddl[ing] while Rome burns. It is excused by two facts: it does not know that it fiddles, and it does not know that Rome burns.”

The basis of this accusation was Strauss’s assessment of the predominant approach in political science, positivism. Positivism attempted to model the social sciences on the natural sciences, which had enjoyed in modernity an uncanny advancement that had meanwhile eluded the study of political things. The primary concept the social sciences borrowed from the natural sciences was the distinction between facts and values. In taking his bearings solely from facts, and refusing to the best of his ability to make judgments of value, the social science positivist eschewed his basic task. Herein lies the fiddling, and the ignorance thereof: to busy oneself with surveys and the like while calling oneself a political scientist, a knower of the things pertaining to our communal life, is to fiddle; but since this accusation of fiddling is itself a value judgment, the political scientist cannot possibly know that he fiddles, nor can he know that he does so as Rome burns. The risk, Strauss shows us, is that the very discipline tasked with guiding the community will busy itself with trifles instead.

In taking his bearings solely from facts, and refusing to the best of his ability to make judgments of value, the social science positivist eschewed his basic task.

As a matter of fact, however, social scientists who subscribe to positivism tend to be advocates of liberal democracy, at least in Strauss’s time and in the West. But Strauss showed that their devotion to liberalism, decent as it may be, is unscientific according to their own standard, just one value among many. Herein lies a still greater risk. If we assert with the positivists that our values do not admit of scientific or even intelligent assessment, then from where will we receive our opinions about good and bad, noble and base, just and unjust? What determines “the direction of interests … which supplies the fundamental concepts” in the social sciences? Strauss concluded that the answer came to be something like fate or history, “a fateful dispensation.”

Positivism thus devolved into historicism, according to which there are no absolute or transcendent truths, certainly not as regards the ends of our actions, or morality and the good; all values, all goals, indeed every thought is historically determined. The decent and earnest liberal positivists populating political science departments in American universities turned out to be professionally and intellectually ill-equipped to counter the most illiberal thinkers of late modernity, even susceptible to them, including some of Strauss’s most notorious contemporaries, like Heidegger and Schmitt.

Historicism, in turn, threatened to exploit the value-neutrality of social science positivism and infiltrate the American academy. Once there, both liberal inclinations and even positivism itself would be seen as just one value among many, since there were no longer any accepted standards for determining the good in truth. Those newly at the university’s helm could thus exploit the void positivism created and steer the “direction of interests” away from liberal ends. Positivism, Strauss effectively showed, had the same weakness as the Weimar Republic; what awaited was the academic equivalent of the Enabling Act, which surrendered the republic to Hitler’s dictatorship.

The History of Political Philosophy

Confronted with these crises, Strauss engaged in a thoroughgoing reappraisal of the history of political philosophy. As one might expect, that reappraisal came with no small measure of controversy; for it involved abandoning contemporary paths and reopening old questions long deemed settled by the leading lights of academic political science. Early in his career Strauss wanted to revive two such questions. First, through his study of the roots of liberalism in Hobbes, he saw that the quarrel between the ancients and moderns—apparently concluded some centuries before the triumph of the moderns—had not been settled adequately and had to be reopened. Second, amid the Jews’ hopes in liberal tolerance being dashed, culminating eventually in the Weimar Republic’s falling to Hitler’s Reich, Strauss was led to study the author of these hopes, Spinoza. Strauss ultimately found Spinoza’s critique of orthodoxy inadequate, so that his advocacy of liberal democracy, with its religious and philosophic tolerance, failed to counter the very premodern views he sought to overcome. Strauss thus made his way back behind the moderns, most decisively in his labyrinthine study of Machiavelli, to what he called “the secret vitality of the West,” Jerusalem and Athens. These cities represented the dilemma that had preoccupied premodern man: the question whether the good life is lived in obedience to divine revelation or lived by unaided human reason. Thanks to Strauss, this dilemma stood before modern man once again.

Strauss saw early on that a critique of our Enlightenment hopes entailed a reevaluation of the relationship between science and society or between the philosopher and the political community. The locus of this relationship is the act of communication, typically in writing; he focused, therefore, on how philosophers of the past communicated, including many modern philosophers, and what they sought to achieve by that communication. This might appear to be “a merely literary question.” Strauss maintained, however, that the question of communication constitutes “an important part of the study of what philosophy is.” It is on this point that Strauss has stirred up the greatest controversy: he suggested that the philosophers of the past have, so to speak, written between the lines to hide their true thought behind publicly salutary teachings. At a minimum, their surface-level teachings need to be restated in light of circumstances surrounding their writings; at a maximum, such philosophers might not have meaningfully held those teachings at all.

It is on this point that Strauss has stirred up the greatest controversy: he suggested that the philosophers of the past have, so to speak, written between the lines to hide their true thought behind publicly salutary teachings.

The implications of this thesis generated the controversy. It exposed nearly the whole of academic historiography as fundamentally inadequate in its interpretive approach to philosophical texts. It required that most, if not all, prior scholarship be heavily qualified, some of it even rejected entirely. And it therefore demanded, finally, that the historiographer see his work more humbly than he might like, as he was asked to bow anew before thinkers whose doctrines had until then been easily digested and thereafter disposed of.

Needless to say, the academy has been slow to warm, even hostile, to Strauss’s Copernican revolution in the study of the history of philosophy. But Strauss was also quite modest in his expectations. In a rare personal statement regarding nothing less than his own happiness, Strauss remarked, “I would be happy if there were suspicion of crime where up to now there has only been implicit faith in perfect innocence.”

As a result of his historical inquiries, Strauss was successful in reopening the question of an evaluative social science, a more robust or fuller alternative to the value-neutral positivism of his day. It would be a mistake, however, to understand his thought through this narrow lens alone. Strauss was not a simple moralist, driven by disgust with the present state of the social sciences to a wholesale endorsement of, say, Aristotle’s Politics. Though he exposed positivist social science as theoretically untenable and spiritually impoverished, he did so while also transforming the study of the history of political philosophy from the moribund old man of political science into an open frontier that awaited young and intrepid pioneers. Strauss succeeded in bringing the fundamental questions of the tradition back to life, against the dogmatism that would deem them already answered and the skepticism that would deny that they even exist.

Classic Natural Right and Socrates

We see, then, that Strauss sought to recover classical philosophy as a still viable alternative, and that this move had a twofold goal: one philosophical and the other moral or political. The moral or political goal involved demonstrating the possibility that human beings have access to trans-historical standards of justice, to natural right. But that goal can be achieved only if one demonstrates first that human beings have access to nature—that is, that philosophy is possible at all. Historicism denies the latter claim, which is more fundamental. Strauss rightly saw this denial as a philosophic and political crisis, especially for the United States, whose founding relied on an appeal to “the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God.” Yet he also saw this crisis as a philosophic opportunity. Historicism, especially in its most radical form, was a welcome ally in the fight against philosophic dogmatism in any form. Though he was suspicious that historicism was merely the contemporary form of dogmatism, he also anticipated that engaging the historicist position, as a peculiarly anti-dogmatic dogmatism, would help “to legitimize philosophy in its original, Socratic sense.”

Historicism benefited the philosopher by exposing the limitations of all philosophic positions or systems. It argued that the apparently linear progress in the history of philosophy actually involves only a development in one area at the cost of regress in another. It thus compelled defenders of natural right to do so on a fundamentally non-dogmatic basis, prior to any particular philosophic position or system yet still properly philosophic. Strauss argued that, prior to arriving at any position, the philosopher had first to grasp the problem—the fundamental problem, as Strauss often put it—to which that position purported to be a solution. The radical historicist, Strauss surmised, would respond with a denial that there even are fundamental problems; he would assert, instead, that the whole the philosopher seeks to understand is always changing, that there is nothing stable about it that would be true for all times.

Strauss responded that the historicist has not adequately understood the history of philosophy, nor even historicism’s own history. He therefore lacks clarity about the fundamental problems with which prior philosophers concerned themselves, what Strauss referred to as “genuine understanding of the thought of the past.” He thus called for a rereading of the history of philosophy outside of the lens of historicism, as well as a critical history of the origins of historicism. Strauss’s historical inquiries were intended in part to answer this call.

A more pressing question for readers, however, is whether the recovery of Socratic philosophy does or does not culminate in the recovery of the classic natural right teaching. Strauss devoted the last decade of his life to an investigation of Socratic philosophy, an investigation he died before completing. Readers should not be surprised, then, if we do little more here than sketch the problem.

Knowledge of the problem of justice is, in Strauss’s account, knowledge that justice rests on mutually exclusive principles. To know the problem of justice is to know its insolubility.

Demonstrating the possibility of philosophy would seem to open the door to natural right; yet Strauss defended the philosophic life on grounds in tension with all philosophic positions, natural right included. Socratic knowledge of ignorance culminates in knowledge of the fundamental problems, among them the problem of justice. Knowledge of the problem of justice is, in Strauss’s account, knowledge that justice rests on mutually exclusive principles. To know the problem of justice is to know its insolubility. From this vantage point, any solution to the problem of justice, including natural right, seems to be untenable.

One suspects that Strauss’s attack on historicism in defense of classic natural right was intended to divert our attention from Socratic philosophy’s more formidable critique of natural right. Strauss created enemies and allies as suited his purposes. But we should approach this suspicion with due sensitivity. Knowledge of ignorance, of the mutual exclusivity of principles, does not mean that there is no objective way to discern which principles apply in particular situations and how. That discernment constitutes the prudence or practical wisdom of the philosopher.

Strauss lived the philosophic life as had all philosophers before him: with one eye on the demands of necessity and the other on the full scope of the questions. His continual emphasis on this twofold character of philosophic writing has the twofold benefit of cultivating both theoretical and practical humility, humility about what can be known and what can be done. By separating these domains, Strauss restored the ancient understanding of the relationship between science and society, philosophy and the city, thereby injecting both with a much-needed dose of moderation. It is this lesson, both urgent and profound, that Strauss offers his concerned and thoughtful readers.

Help us improve Public Discourse! Please complete our Reader Survey 2023.