In my first semester of college, I took a class on “the political novel,” my very first political science course. The professor teaching it, who would become one of the two or three most important mentors in my life, spent much of one session—I think it was on Lord of the Flies—talking about the idea of a “state of nature” in which no government or recognized authority exists, paying particular attention to how Jean-Jacques Rousseau developed the idea of the unspoiled benevolence of “natural man.”

I had never heard of any of this before, but it piqued my interest, and I went to my teacher’s office to ask him more about it. He lent me his copy of Rousseau’s First and Second Discourses; the Second, the “Discourse on the Origins and Foundations of Inequality Among Men,” was the relevant one for our discussion, and I read it on my own, discussed it some more with my professor, and built my term paper around it. That was my backdoor introduction to the study of political philosophy, and I was hooked, taking every course on that subject that my college offered until I graduated.

What I had encountered for the first time, but not the last, was what I will call a bad good book—indeed, a bad great book. Let me explain.

In 1945 George Orwell published a little essay titled “Good Bad Books,” which he defined as “the kind of book that has no literary pretensions but which remains readable when more serious productions have perished.” I have my doubts about his thesis, since a good many of the books he mentions of this kind have indeed perished themselves—they are unknown to me at least, though they may still be known to the English. Some of his examples endure, though: he mentions Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, for instance, and H. Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines. And whether such works endure or not, Orwell is right that certain books give us great pleasure without being exemplars of high literature. Hence they are bad books by a literary yardstick, but good ones with respect to the craft of telling a story that grips our attention—so, good bad books.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.By contrast, the bad good book, or bad great book, is a work of very high literary or philosophical quality, the work of a mind we may have to acknowledge as superior to our own. Often such books have been highly influential, becoming the touchstones for social or cultural changes, even revolutions. Yet in a disturbing number of cases their influence has been malign, and their teaching deeply misguided.

This was the case with Rousseau. He is a brilliant thinker, a compelling writer, someone whose arguments can draw readers into his thought-world and cause them to see their surroundings in a new way, even if they don’t agree with him. It is to Rousseau, for instance, that we owe the powerful idea of “alienation” that came to permeate so many fields of thought. Psychologists, economists, environmentalists, educators all endeavor to find the “natural” human being beneath layers of social convention and artificial relations, to bring that natural creature to life again and find his rightful home in the world.

Yet there is an amazingly high bunkum quotient in Rousseau’s thought. He would have us believe, for instance, that “the first person who … fenced off a plot of ground” and persuaded others to accept his claim that “this is mine” was “the true founder of civil society”—and so something of a criminal destroyer of our peaceful relations with one another in the state of nature. Rousseau thus accomplishes two things: he sells us a bill of goods about his own insupportable version of a Garden of Eden, and he plants the seeds of ideological opposition to all rights of private property. Not for nothing did Edmund Burke once refer to him as “the insane Socrates of the [French revolutionary] National Assembly.”

How ought we to read these good or great books that invite us into unhealthy enthusiasms? How ought teachers to teach them?

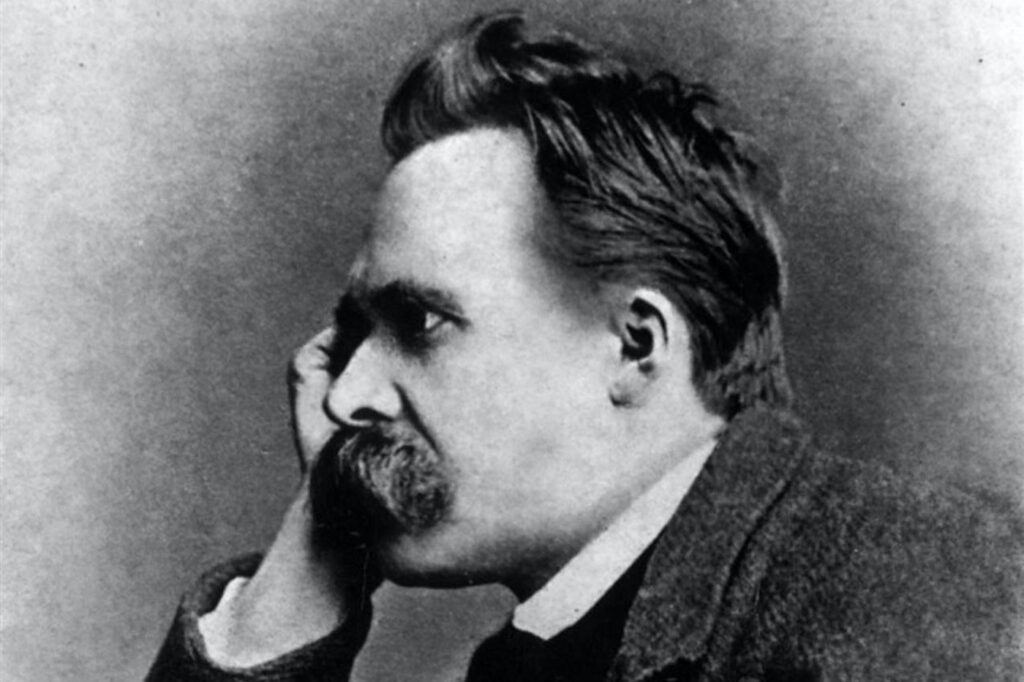

As I moved on in the study of political philosophy, I encountered more such dangerous minds. The next semester I met Friedrich Nietzsche, the great arsonist of all received ideas. Nothing is safe from his blazing torch. Nietzsche is aphoristic, unsystematic, febrile. He is a very great hater, and young men in particular find his passionate hatreds alluring because they seem liberating. (I have never met a female Nietzschean, which may say a lot.) He hates the Jews, and Christianity, and Socratic rationalism, and anything that smacks of conventional morality or liberal politics. Nietzsche was the fellow who proves the point about the proximity of genius to madness; he ended his days quite insane. The genius, however, was genuine. Is there a straight line from Nietzsche to Adolf Hitler? Opinions differ. But there is at least a crooked one.

Philosophical works like Rousseau’s and Nietzsche’s are aimed at producing enthusiasts. They are attempts to change the world by arguments, appeals, sentiments, denunciations. How ought we to read these good or great books that invite us into unhealthy enthusiasms? How ought teachers to teach them?

Teachers have their own opinions about which books they assign are fit candidates for their students’ enthusiasm, and which are not. How could they not? They believe they know which are the good good books, and which are the bad good books. (Everyone wants to avoid the simply bad.) Yet as difficult as it may be not to push their opinions on their students, they must try their level best not to do so. Each book—Rousseau equally with Locke, Aquinas equally with Nietzsche—must be given its fair hearing, read and discussed with a receptive yet critical mind. Each book must be permitted, even assisted, to make its strongest case to the reader—and the strongest case against its argument must be thoroughly aired as well.

Pedagogically, this will require different approaches with different students. Over my years of teaching, I have assigned Machiavelli’s Prince numerous times. For the most part—again, especially with young men—I found it necessary to tamp down student enthusiasm for the Florentine’s ruthless realism about political life. “He’s telling it like it is!” was the cry from the student seats. But one year, long ago, teaching at a Catholic university, I encountered a cohort of students genuinely shocked and appalled by Machiavelli. Then it became my duty to compel them to take his arguments seriously, and to ponder what he might be right about. To read with an open mind is to be both receptive and critical, and if a student overbalances in either direction, the teacher’s duty is to push the other way.

One more example. In a fit of wokeness three years ago, Princeton University decided to scrub the name, and even the image, of Woodrow Wilson from virtually every corner of the campus. A residential college named for him (such colleges were his idea) was renamed; the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs simply dropped the first two words of its name; even paintings that depicted Wilson in Prospect House, the faculty club that was once his home, vanished from view.

Now Woodrow Wilson, who graduated from Princeton in 1879, returned to teach there in 1890, becoming the university’s president in 1902, a position in which he served more than eight years until he became governor of New Jersey. It is not saying too much to allow that Wilson made Princeton the world-class university it is today. His only rival among its many distinguished graduates is James Madison, class of 1771. For the better part of a century Wilson was lionized by liberals and Democrats as one of the founding fathers of progressive politics in American domestic life and of liberal internationalism in foreign policy. But Wilson was a racist who segregated the federal civil service, turned a blind eye to Jim Crow in his native South, and showed D. W. Griffith’s Klan-fan flick Birth of a Nation in the White House. Hence his peremptory posthumous defenestration at Princeton.

The teacher must be a wrestling coach, instilling in his students a readiness to grapple equally with every kind of argument, accepting nothing on which they have not tested their own grip.

I am no progressive, and no admirer of Wilson’s politics in virtually any of its dimensions, though I can concede him a point here or there. But two years ago I offered a Princeton seminar on Wilson’s thought because he was a brilliant and influential political scientist who ought to be required reading for anyone who wants to understand modern American politics. His 1908 book Constitutional Government in the United States, just one of his major writings we studied, is a pivotal work in the development of progressivism. It is, in my view, a bad good book, treating the Constitution’s framers as backward children of a benighted age, celebrating the possibilities of an organic, “living” Constitution, and laying the intellectual ground for the aggrandizement of presidential power over the next century. But Wilson’s observations and arguments can’t simply be dismissed; they must be confronted with the ready grip of a wrestler who is prepared to throw and be thrown. Some readers will think him right about things that others are sure he’s wrong about. Interesting discussions may ensue!

The image of the wrestler is apt. The first great writer of political philosophy in the West was a wrestler who went by the sobriquet Plato, “broad-shouldered.” And, as I’ve said, the bad good (or great) books must be read and taught in just the same way as the good great books. The teacher must be a wrestling coach, instilling in his students a readiness to grapple equally with every kind of argument, accepting nothing on which they have not tested their own grip. One hopes that the best of the great books will pin them to the mat and make them cry “uncle,” while from the worst of them they will wriggle free but not without a struggle. But the coach throws the match in advance if he celebrates his favorite books and will brook no argument with them, or if he condemns—or refuses to assign—the bad great books and will not let them make their own case.

We are entitled to hope, in short, that our students will not become Machiavellians, Rousseauans, or Nietzscheans—or Wilsonians—if we are convinced that the influence of such thinkers is malign. But the only responsible way to act on that hope is to take the risk that they will become such devotees, by reading all books of the first rank with critically receptive minds ourselves and demanding that our students do likewise.