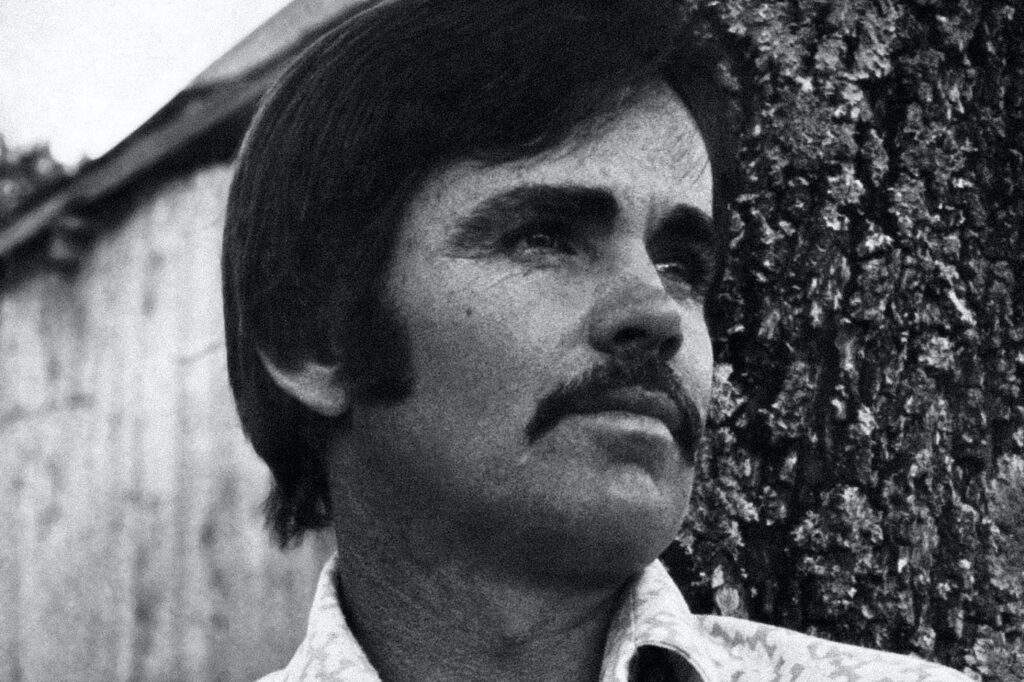

Cormac McCarthy, who passed away today, ranks among the most important writers of fiction American society has ever produced. There is ample agreement on this point.

When it comes to interpreting the meaning of his work, though, there is much less consensus.

McCarthy handled big themes in his work, and that is true in his most recent novels: The Passenger and Stella Maris. These two books form a single narrative of siblings Alicia and Bobby Western’s extraordinary lives. We find here meditations on meaning and meaninglessness, human knowledge, death, spirituality, and the nature of the material world. Truth and beauty, reason and faith, love and sex: it’s all here. Mingled with these themes is obsessively detailed description of machines and contraptions of all sorts (especially guns and cars)—another perennial McCarthy interest.

Many critics read McCarthy’s novels the way they do so many other art forms: devoid of the possibility of hope, transcendence, and a living God. But this often glosses over the genuinely conflicted character of the art. The Passenger and Stella Maris offer more than just an artistic representation of reality’s inescapable brutality. They forcefully struggle with the greatest questions of human existence. Like any good work of art, these books don’t allow any reader—religious, atheist, materialist, Christian—to walk away feeling perfectly comfortable in their understanding of the world.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.In The Passenger and Stella Maris, we find meditations on meaning and meaninglessness, human knowledge, death, spirituality, and the nature of the material world.

The Passenger’s plot involves a plane crash with a missing corpse, and one of the main characters, Bobby, is pursued by shadowy and sinister figures who seem to suggest he played a role in that body’s disappearance. But this plot serves as a frame on which McCarthy hangs his reflections on deeper questions. The mystery of the plane crash is never resolved, and readers are left wondering if this is McCarthy’s way of suggesting that the world’s meaning is elusive and ultimately nonexistent. But, as is always the case with McCarthy’s books, put too much stock in tidy conclusions and you will be disappointed.

Slate’s Laura Miller interprets these novels as many other readers will. She wonders why McCarthy would have bothered this late in life to write two more books with a view of life as “brutal and meaningless.”

These books do contain brutality, and meaninglessness haunts their pages. But they offer much more than the total bleakness that professional critics often perceive in them. To be fair, Alicia Western, whose account of reality is detailed in Stella Maris, provides evidence to support Miller’s reading. She is a solipsist who, when a young girl, read George Berkeley on the physiology of vision and concluded that the world existed only in her youthful head. Alicia often appears unrelentingly pessimistic. She has a disturbing—and incestuous—obsession with her brother.

Yet McCarthy gives Alicia much more complexity than most of the critics have noted. She fiercely struggles with the fallen aspects of her character. A first-rate violinist, she lovingly describes music as sacred. She especially admires Bach, and she knows what (or Who) motivated the great German composer’s music. When she describes having spent her inheritance on a rare Amati violin, she recalls weeping when she played it for the first time. Tears come also when she recalls her pure bliss at the sound of Bach’s Chaconne emerging from her violin. The instrument must have originated in the mind of God, she insinuates, so perfect is its construction.

Amid this discourse on music, Alicia tells Cohen, her psychologist and interlocutor through the entirety of Stella Maris, what she believes to be “the one indispensable gift”: faith.

This question of faith is powerfully demonstrated in Alicia’s account of her father’s final days. This man, a resolute materialist throughout his life, developed cancer almost certainly because of his work with radioactive material in developing the atomic bomb. He was told by physicians in the United States that there was no chance of recovery. His materialism gave him no resources for contending with his mortality, and so he embarks on a futile search to extend his life with alternative treatment in Mexico. He asks his son to accompany him, but Bobby refuses—a decision he regrets for the rest of his life.

How do McCarthy’s characters respond to mortality? Eternal life is “unlikely,” Alicia tells Cohen, yet the “probability is not zero.” In the seventeenth century, Blaise Pascal formalized the rationality of religious belief in just these terms. Given the non-zero probability of God’s existence, one follows reason in betting on the infinite gain (eternal life with God) from a life of belief against the limited benefits (unrestricted pleasures during a finite existence) from a life of disbelief.

How do McCarthy’s characters respond to mortality? Eternal life is “unlikely,” Alicia tells Cohen, yet the “probability is not zero.”

McCarthy is too clever a writer to have Alicia straightforwardly take up Pascal’s wager. Instead, he puts into her mouth these words: “[I]t may even be that in the end all problems are spiritual problems. … The spiritual nature of reality has been the principal preoccupation of mankind since forever and it’s not going away anytime soon. The notion that everything is just stuff doesn’t seem to do it for us.”

Cohen asks if that’s true for her. She responds: “That’s the rub, isn’t it?”

We don’t learn from Alicia her answer to that question, but her reflection on the incompleteness of science and mathematics and their compatibility with faith suggests much. Acceptance of some version of God is, she relates, “a lot more common among mathematicians than is generally supposed.” Kurt Gödel, the figure in math she most admires, “became something akin to a Deist. … [He] never says outright that there is a covenant to which all of mathematics subscribes but you get a clear sense that the hope is there. I know the allure. Some shimmering palimpsest of eternal abidement.”

McCarthy critiques Alicia’s coldly logical worldview (which eventually leads her to self-destruction) through a character she calls the “Thalidomide Kid.” He appears to exist only in her mind, though, inexplicably, the Kid visits Alicia’s brother Bobby after her death to reveal to him her final verdict of the world: “She knew that in the end you really cant know. You cant get hold of the world. You can only draw a picture. Whether it’s a bull on the wall of a cave or a partial differential equation it’s all the same thing.” (The missing apostrophes are an element of McCarthy’s style.)

The Kid’s name, Thalidomide, is a drug that was briefly considered a miracle cure in the West during the mid-twentieth century. It eliminated the nausea accompanying pregnancy, one of the oldest maladies of human existence but one that actually helps ensure the health of both child and mother. Thalidomide’s safety in pregnancy was not evaluated during the drug’s testing. Scientists thereby failed to discover the catastrophic birth defects it produced in human infants. The Kid’s complicated character, which includes evident concern for Alicia’s well-being despite his caustic personality, might be explained as her emotional core, the more intuitively aware part of herself, speaking back subconsciously to her rational self, which, like Thalidomide, promised balm and delivered misery.

Alicia herself labors toward the complex understanding of the world represented by the Kid, who shows an awareness of the limits of logic and reason. She sees intelligence—defined as mastery of mathematics, the purest form of knowledge—as bestowing a certain superiority over others. Yet she also knows that it “is a basic component of evil.” The unintelligent are typically understood as harmless, while ingeniousness is often associated with the diabolical: “What Satan had for sale in the garden was knowledge.” Throughout the books, the Manhattan Project on which their father worked is recognized by both Alicia and Bobby as the moral equivalent to eating of the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil.

Alicia’s perspective on religious faith doesn’t arrive in full view until the conclusion of The Passenger, when her brother Bobby makes the most profound discoveries on this topic.

After her suicide, he goes to see Alicia’s friend Jeffrey in Stella Maris, the psychiatric hospital where Alicia had admitted herself. Her friend tells Bobby that he had asked her how she could believe in the Kid but not in Jesus. “Everyone is born with the faculty to see the miraculous. You have to choose not to,” he tells Bobby. Jeffrey reveals that Alicia had noted an odd discolor in the eye of another woman in the institution and told doctors, who detected a cancer and saved her life by removing the eye. Subsequently, however, the woman grew depressed and took her own life. Bobby realizes that the death of this woman, whom Alicia had intended to save, led his sister to her own demise. The name of this suffering woman was Mary, and she and Alicia were housed in an institution bearing the Latin name “Star of the Sea.” This is an ancient title for the Mother of God, which originated in a transcription error linked to an etymology of the Hebrew name for Mary. The title designates the Virgin Mother’s protection of sailors and others who travel at sea.

Through the novel’s symbolic language, Alicia is thus connected intimately with the Madonna, who comforts her suffering child and suffers herself. Alicia’s mathematical genius cannot extinguish her emotional need to alleviate the pain of others (Mary of Stella Maris who suffered eye cancer), and after her troubled life’s voyage she seeks healing in the bosom of the Mother (Stella Maris hospital). That she takes her own life is no certain indication she is lost. There is more than enough evidence of her grappling toward a spiritual solution to suffering, enough to suggest that she hoped she might yet find solace.

At the end of The Passenger, Bobby lives in a lighthouse in Spain, looking over the sea that is protected by Stella Maris. He meets an unnamed individual. This could be the ghost of his deceased friend John Sheddan, who left a deathbed letter bidding Bobby in unabashed Christian language to “Be of good cheer.” The friend asks Bobby what he’s doing there, which leads to this exchange:

I live in a windmill. I light candles for the dead and I’m trying to learn how to pray.

What do you pray for?

I don’t pray for anything. I just pray.

Why does he pray? Perhaps for the good reason that his grandmother, Granellen, told him to. Granellen might be overlooked by readers, especially those determined to find no hope in these works. She represents the rootedness in the traditional world that McCarthy has described in detail elsewhere, for example, in Sheriff Bell’s wife Loretta of No Country for Old Men.

“Do you believe in God, Bobby?” Granellen asks. “I don’t know, Granellen. … The best I can say is that I think he and I have pretty much the same opinions.” She advises him: “You have to believe that there is good in the world. I’m goin to say that you have to believe that the work of your hands will bring it into your life.”

Bobby has by the end of the two novels suffered much loss. He didn’t save his sister from her demons. He comprehends the legacy he inherited from his father, who helped bring an unprecedented destructive power into the world.

But McCarthy has given us reason to believe that this is not the whole tale. These books hint that we might do well, when we face what Alicia named as “the horror beneath the surface of the world,” to emulate the practice of our ancestors. For they trusted that there would always be protection from that horror, so long as we do not lose faith. Alicia’s commitment to compassion and Bobby’s prayerful penitence give the reader reason to suspect that McCarthy did not shut the door on God before his life ended.