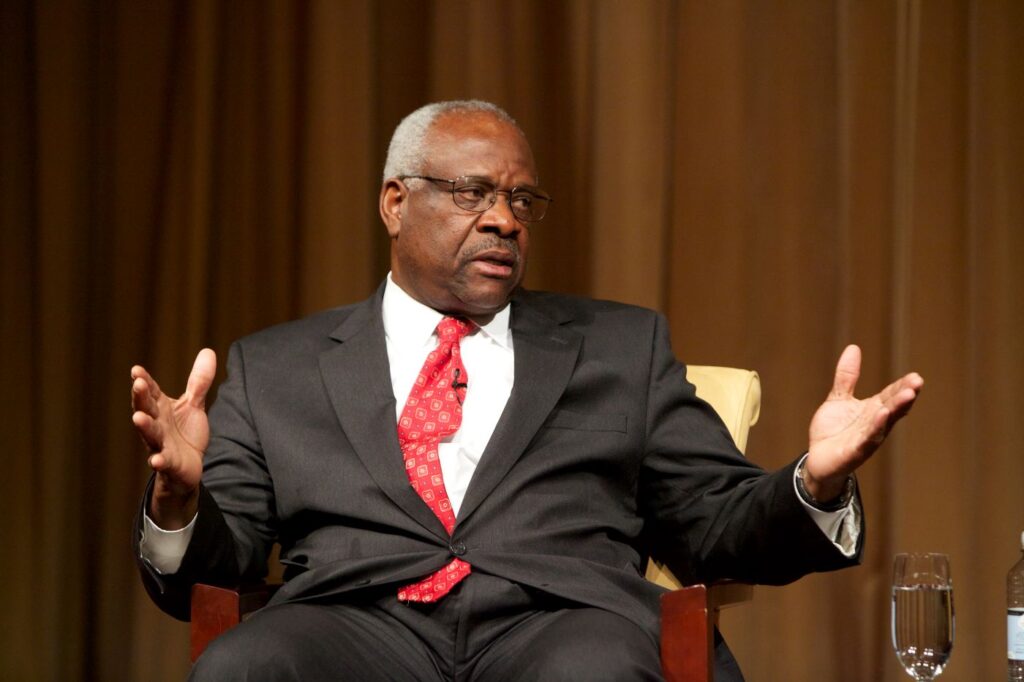

To many, Justice Clarence Thomas is little more than a sixth vote for the conservative wing of the Supreme Court, mostly because he was once known for rarely speaking during oral arguments. In 2016, Justice Thomas asked several questions during arguments, the first time in ten years, and since the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, when the Court opted for more structured arguments over Zoom, Justice Thomas has proved to be a sharp questioner.

But despite his long silence on the bench, Justice Thomas has always written extensively, often crafting dissents when he disagrees with decisions and concurrences when he agrees with results but not the reasoning. It is in these opinions that Justice Thomas shows an independent streak: more than other originalists on the Court, like the late Antonin Scalia, he will vote to overturn established precedent. He is often willing to break with conservative colleagues if his methodology leads him to such a conclusion, as was the case in his notable split from Justice Scalia in Hamdi v. Rumsfeld.

To many, even if Justice Thomas does not defer to conservative colleagues, his deference to his methodology suggests he is a cold individual with little regard for the parties who would be hurt by the logical conclusions of his interpretation. If Justice Thomas cannot be stereotyped as lazy, he can be deemed cruel.

Judge Thapar’s Narrative Focus

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.It is against this backdrop that Judge Amul Thapar of the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit published his recent book, The People’s Justice: Clarence Thomas and the Constitutional Stories That Define Him. In a public talk at the American Enterprise Institute, Judge Thapar stated that he originally intended to write a book defending originalism from the accusation that it always strikes against the “little guy.” He notes, however, that his wife dismissed the pitch as “boring.” Instead of writing a book about originalism for laypeople, Thapar decided to focus on the constitutional stories leading to the decisions. The choice of Justice Thomas as the central protagonist came from the fact that, since the passing of Justice Scalia in 2016, he is originalism’s primary advocate on the Supreme Court.

Judge Thapar sets out to fight the misconception that Justice Thomas (and constitutional originalism) “favors the rich over the poor, the strong over the weak, and corporations over consumers,” by profiling twelve constitutional stories in which Thomas’s originalism “more often favors the ordinary people who come before the Court.” As Thapar explains, “the core idea behind originalism is honoring the will of the people.”

The book explores several different legal areas, including eminent domain, medical marijuana, state regulation of the sale of violent video games, school vouchers, and cross-burning, among many others. Judge Thapar presents these cases as stories that focus on the motivations and challenges of the characters. The book does not aim to provide readers with legal arguments surrounding important questions, such as whether the First Amendment prohibition of religious establishment prohibits school vouchers. Instead, Thapar focuses on the motivations of the political leaders and parents in defending the program. The framing of these stories is meant to share the experiences of these people rather than to give readers an understanding of the contours of the Constitution.

But while the narrative focus is the book’s greatest strength, it is also the source of its weaknesses. Certainly, the stories are easy to follow and the individuals Judge Thapar chooses as his protagonists are compelling. But the narrative structure quickly takes on a David–Goliath dynamic. The protagonists are ordinary people pitted against fierce opposition.

Take, for example, Kelo v. New London and Gonzales v. Raich. Kelo tells the story of a woman trying to protect her home from being taken through eminent domain. Raich tells the story of California residents who sought to grow marijuana for their own personal, medicinal, and “intra-state” use without running afoul of government regulation of inter-state commerce. In these cases, the David-Goliath dynamic is implied: both tell the story of ordinary people in conflict with the government. But this dynamic is less obvious in other stories Thapar profiles. For example, in Brown v. Electronic Merchants Association, in a majority decision written by Justice Antonin Scalia, the Court struck down a California law against selling minors violent video games. The Court held that the law violated the First Amendment. The conflict in Brown was between the video game industry and California. But which side, business or government, is David and which is Goliath? Though the government tends to be painted as the villain, in his dissent, Justice Thomas argued in favor of upholding the state law, claiming it would serve families and children, an interest worth protecting.

Judge Thapar argues that in cases like Brown and Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, Justice Thomas’s is the voice of the people, particularly when “the people” are not a party to the case. Brown was a suit filed by a profitable industry against the government. Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, on the other hand, was a case dealing with the constitutionality of school vouchers. In his concurring opinion, Thomas wrote that the vouchers did not violate the Establishment Clause. That opinion, like his dissent in Brown, focused less on the government program itself than on the community meant to be served. In Brown, Thomas noted the importance of education and the significance that a meaningful education can offer the communities meant to be served by Cleveland’s school voucher programs: inner-city students.

While Thomas’s background influences his decisions, any application of originalist theory cannot ignore the facts before the Court.

Originalism is sometimes called formalistic, an accusation that some defenders of the theory, like Justice Scalia, have embraced. Those who would apply a “formalistic” theory are taken as uninvolved in the process, merely churning the facts through an analytical process without regard for the effect the application would have on the lives of the parties. Justice Thomas’s admirers would claim this is an unfair depiction of him. On one hand, some commentators have suggested that Thomas’s application of originalism is less mechanical than Scalia’s, taking into account other considerations. On the other hand, those who know Justice Thomas tend to emphasize his care for others in personal settings.

The narrative focus of the individual stories is Judge Thapar’s attempt to bridge the gap between a formalistic theory of interpretation and the experiences of real people. He attempts to do this by sharing how, in his application of originalism, Justice Thomas acknowledges how constitutional interpretation affects both the parties before the Court and as the people in general. Furthermore, it shows the “human” element of Thomas, attempting to prove that a man so often described as an enigmatic figure cares deeply about the social implications of his decisions.

However, while stories like the one in Zelman support Thapar’s presentation of Thomas as the “people’s justice,” other stories do not directly support this thesis. For example, Judge Thapar profiles State Farm v. Campbell, a case dealing with the imposition of punitive damages against the insurance giant. In that case, the majority ruled that a Utah state court’s punitive damages award against State Farm was too high. Justices Ginsburg, Scalia, and Thomas dissented. In the book, Thapar notes only that Thomas wrote a “short dissent,” without saying much more. Given this scant discussion of Justice Thomas’s involvement in the case, it is hard to see how State Farm is a constitutional story that “defines” him.

Originalism for Everyone

The People’s Justice communicates a complicated theory of constitutional interpretation to laypeople. The stories provide an a helpful glimpse into constitutional law and the application of originalism in interpreting the Constitution. But it is by no means a complete presentation of the theory, or of Justice Thomas himself. Nonetheless, Judge Thapar’s narrative style does offer an important contribution to the discourse on Thomas. Many biographies have delved into who Justice Thomas is by examining his background and trying to provide more context for his rulings. Thapar contributes to this literature by reminding us that while, like everyone else, Thomas’s background influences his decisions, any application of originalist theory cannot ignore the facts before the Court. Originalism is a theory of interpretation, but like any form of legal interpretation, it means little unless applied to facts. And facts are wrapped up in stories. Judge Thapar’s book is a reminder not to forget this.