The online right has gone ballistic over Justice Amy Coney Barrett. The precipitating cause was her vote in Department of State v. AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition, but it comes after a string of idiosyncratic votes in medium-profile cases. Never mind that Barrett provided the fifth vote to abolish Roe v. Wade at long last. Never mind that she has put Justice Gorsuch in the minority as he seeks to expand the rights of criminals, immigrants, and tribes. Never mind that her mere presence on the Court has neutralized the chief justice’s strategic power as “the fifth vote,” a fact that has surely enabled the current Court to overturn hated precedents—apart from Roe—such as Grutter, Chevron, and Lemon. Never mind that President Donald Trump himself doesn’t seem to agree, calling Barrett “a very good woman” and “very smart.” No, we are to believe that she’s the second coming of David Souter—a justice whose appointment was a grave mistake.

This view is wrong. In today’s essay I will explain how Barrett allowed President Trump and then–Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell to flip Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s Supreme Court seat. Tomorrow I will show that, on the Court, she has behaved exactly as she told the Senate that she would, and I will conclude with observations on how conservative lawyers should respond to that.

The 2020 Vacancy

When Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg suddenly died in late September 2020, Barrett was a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit and the proverbial woman for the moment. At the time, I was chief counsel for nominations on the Senate Judiciary Committee under Chairman Lindsey Graham.

The situation in the Senate was precarious. We had to get Barrett confirmed before the election because lame-duck uncertainty would risk the seat. This meant we had a month to complete a process that normally takes at least three—in the midst of a presidential election, during the COVID pandemic, with the media hitting each of our members over alleged hypocrisy.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.The supposed hypocrisy, of course, stemmed from the decision by McConnell four years earlier to prevent the consideration of Merrick Garland for the Supreme Court seat left vacant by Antonin Scalia’s death. McConnell argued that the seat should be filled by the next president because it was an election year in which the president and the Senate majority were of opposing parties. Due to the makeup of the Republican Conference in 2016, McConnell and his allies relied heavily on the election-year argument to stave off any rebellions from moderates. That argument, of course, would become rather inconvenient in the fall of 2020 as the media focused on the fact that it was an election year—while ignoring that the presidency and the Senate were controlled by the same party, unlike in 2016.

It was also beside the point. The real justification for both blocking Garland and replacing Ginsburg was the existence of a Republican majority and the ability to use it. McConnell’s liberal critics—including his most recent biographer—pointlessly complain that “the Biden Rule,” on which McConnell and then–Judiciary Chairman Chuck Grassley relied in 2016, was “not a precedent” because Senators Joe Biden and Chuck Schumer only threatened to block nominees without actually doing so. Well, sure, but the Biden Rule isn’t a precedent: it’s a justification. Just because Biden and Schumer didn’t have the opportunity to set a precedent—which is a Senate term of art—that doesn’t mean that they wouldn’t have done so if the opportunity had arisen. It was the universal knowledge of Democratic perfidy among Senate Republicans that justified McConnell’s hardball tactics.

So what could McConnell do in the fall of 2020? Confirm Barrett. That McConnell would seek to fill the seat was obvious to anyone who knew him—including his colleagues in the Republican Conference with whom he had spent the summer laying groundwork—but whether he could do it depended on 49 other Republican senators actually joining him. It was Barrett who made this possible, as McConnell recognized at the time through his advocacy for her.

The Politics of the Barrett Nomination

The first issue was defensive politics, which dictated that the pick needed to be a woman. As a political matter it would have been untenable to replace Justice Ginsburg with a man. With an election mere months away, and college-educated women being a reliable and increasingly progressive voting bloc, subjecting them to the indignity of replacing “the Notorious RBG” with a man would have further radicalized them. This was a political reality that President Trump had long understood—he was, after all, widely reported to have wanted a woman available to replace Ginsburg in the event a vacancy arose during his presidency. “Owning the libs” by replacing the hero of feminism with a man plays better on X than it would have at the polls.

The second issue was offensive politics. Ever since the late Senator Dianne Feinstein had told then-Professor Barrett, “The dogma lives loudly within you,” Barrett had been a folk hero among Catholic Republicans and social conservatives. Almost every Catholic in the D.C. area had a “dogma” mug. A nominee with an established, independent political brand was manna from heaven in terms of generating support for a snap confirmation among potentially squeamish Republicans.

Beyond Barrett’s brand was what she represented. A conservative Catholic mother of seven from Indiana—one who had made it to the top of the legal profession—she validated a way of life that was both alien to opinion leaders and very familiar to the kind of educated women who had remained within the GOP fold. Judiciary Committee Chairman Lindsey Graham noticed this himself during her hearings and said as much before her second day of questioning. He observed:

[T]his hearing, to me, is an opportunity to not punch through a glass ceiling, but a reinforced concrete barrier around conservative women, and you are going to shatter that barrier. I have never been more proud of a nominee than I am of you. . . .

And this is history being made, folks. This is the first time in American history that we have nominated a woman who is unashamedly pro-life and embraces her faith without apology, and she’s going to the Court. A seat at the table is waiting on you, and it will be a great signal to all young women who share your view of the world that there is a seat at the table for them.

This will not be celebrated in most places. It will be hard to find much commentary about this moment in American history. But in many of our worlds, this will be celebrated.

“In many of our worlds, this will be celebrated.” It was. The kind of grassroots support we saw in the Senate for Barrett was unlike any we had seen before. Activists told me at the time that their volunteer numbers shattered internal records. And Graham—himself locked in a serious reelection campaign where he was being significantly outspent—saw his fundraising skyrocket as he championed Barrett’s cause.

This isn’t what some of Barrett’s critics call—ridiculously—“DEI”; it’s politics. Barrett was a highly attractive candidate to a particular, important constituency of the Republican coalition—religious women—who were ready and willing to make their voices heard to wavering senators.

The Barrett Confirmation Process

Equally important was the question of mechanics. As I noted above, we had around a month in which to do something that typically took at least three. The business of preparing nominees for their hearings is grueling. They read bookcases full of memos and judicial opinions and then subject themselves to merciless grilling sessions where some of the best lawyers around pick them apart—all while meeting scores of senators for private questioning. At the same time, the Judiciary Committee fights over and reviews their documents—opinions, speeches, briefs, public-service work products. In order to get this done in a month we needed a nominee who would not require much preparation herself and who didn’t have a voluminous record with which to bog down the Senate in procedural fights.

Without Amy Coney Barrett, whoever Biden would have put in that seat would have made Ruth Bader Ginsburg look like Robert Bork.

Barrett had a manageable record. She had been a judge for around three years, which provided an established but digestible record. (As my staff told me at the time, it helped that she was a superbly clear writer.) Her previous service as a professor also meant that her prior career was not burdened with countless legal briefs or interminable executive-branch work emails. At one point, when Democrats complained that they wanted documents from Notre Dame, I asked if they really expected me to ask for the minutes of the faculty parking committee.

Barrett was also a savant when it came to testifying before the Judiciary Committee. I don’t know how much time she spent in formal preparation, but it couldn’t have been more than a weekend—and it came on the heels of her having met with a record number of senators over the course of a few days. Nevertheless, she performed brilliantly. She knew the ins and outs of the law and her record. She pushed back on Democrats without being abrasive—reducing them to juvenile stunts about Obamacare. Her personal story allowed her to instantly blunt Senator Dick Durbin’s George Floyd attacks, which were clearly designed to alienate Senator Tim Scott of South Carolina—who had a record of opposing Trump nominees he viewed as insensitive to African Americans.

My own theory is that Barrett’s decades of engaging in Socratic dialogue with students who hadn’t done the reading was the perfect training for handling Senate Democrats.

Regardless of why she performed so well, the fact is that she did. Indeed, the hearing was so effective that her longtime nemesis, Dianne Feinstein, announced that it was the best she had ever seen. That performance, coupled with the enthusiasm Barrett’s nomination catalyzed among the GOP’s conservative base, is what allowed McConnell to keep 51 votes together and invoke cloture on her nomination.

Republicans couldn’t have filled the seat without Barrett. McConnell knew this, and for that reason insisted that she needed to be the nominee. Without Amy Coney Barrett, whoever Biden would have put in that seat would have made Ruth Bader Ginsburg look like Robert Bork.

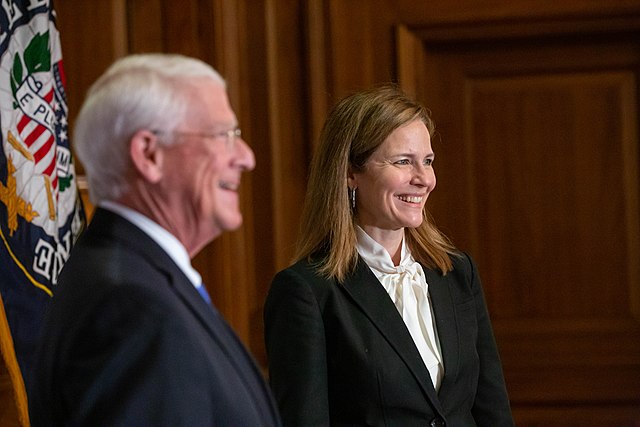

Image courtesy of the Office of U.S. Senator Roger Wicker and sourced via Wikimedia Commons.