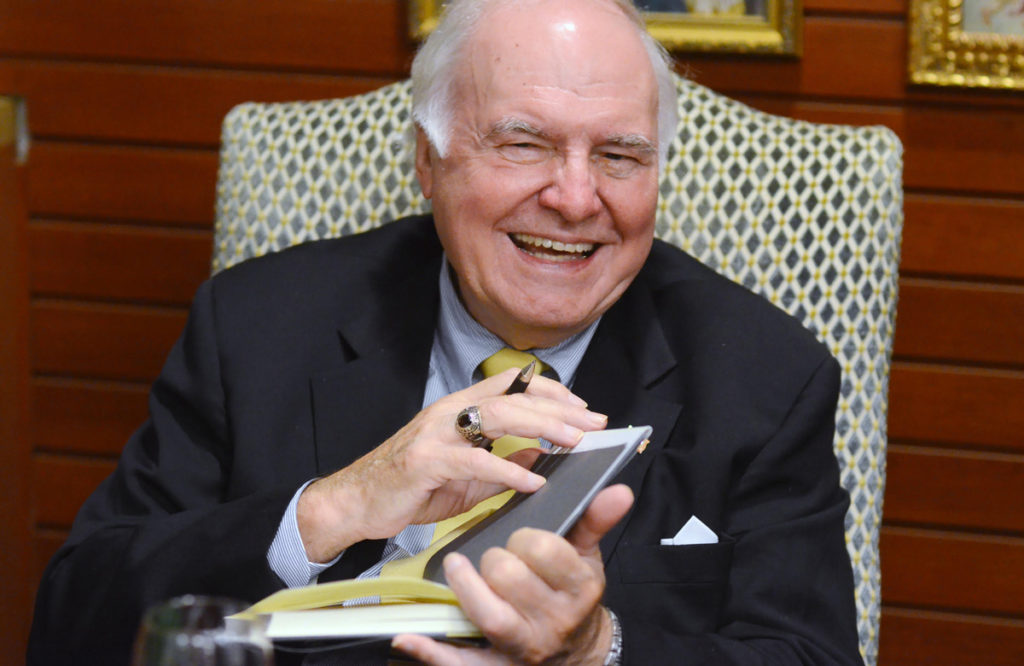

Since Michael Novak’s recent death at the age of eighty-three, I have been thinking more and more about his extraordinary life and legacy, and reflecting on how much he taught me through his writings and our many conversations and how fortunate I have been to get to know and cherish him as a friend.

The author or coauthor of close to fifty books, Michael Novak is widely acknowledged to have been one of the most prolific and influential intellectuals of his generation. He is certainly best known for his now classic work The Spirit of Democratic Capitalism. That book, in which Novak brilliantly formulated a theology for capitalism, did much to earn him the prestigious Templeton Prize and is now widely recognized as one of the most influential books of the past fifty years. I have read and learned much from many of Michael’s books. I must confess, however, that as a devout baseball fan, one of my personal favorites is his wonderful book The Joy of Sports, which deserves to be on the library shelf of every serious sports fan in America.

Perhaps more than any other contemporary scholar, Michael Novak has analyzed and documented the important role of religion in the American founding and in the lives of the Founding Fathers. Through his writing and teaching, he has inspired new academic interest in the topic. When he worked at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) in Washington, DC, he led lectures and symposia on the topic, as well as an ongoing monthly scholarly colloquium on religion and the founding of the American republic. This was cosponsored by the Library of Congress and attended by scholars, journalists, and university professors. As a participant in this colloquium during one of my years in Washington, I can personally attest that it encouraged and inspired my growing interest and subsequent research in the field of religion and the American founding.

It was after one of these colloquia at the Library of Congress in 1999 that Michael first invited me for lunch at AEI. This was the first of several lunches that I would enjoy as his guest and the true beginning of an eighteen-year friendship. At the time, I was beginning my research on Pope Pius XII and the Jews, which would eventually culminate in my book The Myth of Hitler’s Pope. With Michael’s encouragement, I was able to think through and refine many of the ideas and arguments that eventually made their way into my book. Michael soon became my adviser and mentor as well as my friend.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.After I completed that book, Michael began encouraging me to devote my attention to the relationship of Jews and Judaism to the American founding, a topic that was of great interest to me. In my view, his two books on religion and the American founding—On Two Wings: Humble Faith and Common Sense at the American Founding and Washington’s God: Religion, Liberty and the Father of Our Country, which was coauthored with his daughter, Jana—are two of his most important books. They are destined to become classic and enduring works in the literature on the Founding Fathers.

In On Two Wings, Novak brilliantly argues that “the leaders of the American Revolution were not, like the leaders of the French revolution, secularists out to erase or destroy religion.” Rather, as Novak points out, “the majority of the Founders were men of religious belief,” who supported religious liberty and the role of religion in public life. Indeed, as Novak notes, during early September 1774, the very first act of the First Continental Congress was to publicly pray together for God’s Divine Providence in the face of the British bombardment of Boston.

As Novak documents, even James Madison, who is usually thought of as one of the least religious of the Founders, went back for an extra year of religious study at Princeton after his graduation in 1774. He studied Hebrew and the Hebrew Scriptures under the direction of Princeton’s president, the Reverend John Witherspoon. One of his generation’s greatest defenders of religious liberty, Witherspoon greatly influenced the religious life and thought of many of the Founders, Madison included. As President, Madison followed Washington’s precedent, continuing to pay clergy to serve as chaplains in the military and issuing religiously inspired Thanksgiving Day proclamations.

In Washington’s God, the Novaks demonstrate that George Washington “insisted upon speaking openly of God.” Washington had no reservations about publicly acknowledging the importance of religious faith for the new nation’s destiny. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington frequently invoked God’s assistance and blessings for the American cause, often in words that made a deep impression on his fellow citizens. General Washington “gave orders that each day begin with a formal prayer, to be led by officers of each unit,” so that the men of the Continental Army might “secure God’s blessing on their efforts every day. . . .” Indeed, Washington was far more public in his declarations of religious faith than many political leaders and presidents who would come after him. He “reached beyond the Constitution to swear his oath of office upon the Bible; he even kissed the Bible upon taking the oath.” And, although it is ignored by most of Washington’s biographers, in his General Orders to the Continental Army on July 2, 1776, Washington first entered the phrase “under God” into American public language. It is believed that this usage was the inspiration for Abraham Lincoln’s famous description of the United States as “one nation, under God.”

Rich in its insight and analysis, Novak’s discussion in On Two Wings brilliantly illuminates the Hebrew influence on the American founding and documents the way in which the Jewish vision of the world outlined in the Hebrew Bible shaped the religious and political thought of many of the Founding Fathers. As Novak so poignantly illustrated, the idiom of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob was a religious lingua franca for the founding generation. Much like their Puritan ancestors, the Founding Fathers venerated the Old Testament and the ancient Jews of the Hebrew Bible, comparing their own struggle with Great Britain to that of the ancient Israelites’ struggle with Egypt.

No other contemporary scholar has written with more clarity and insight than Michael Novak on the intersection of early American politics and religion, on the religious faith of the Founders, and on the religious roots of the American Republic. He has inspired a new generation of scholars and students, including me, to devote ourselves to the topic, which had previously been much neglected. In the field of religion and the American founding as well as many others, Novak will be remembered as one of the most prolific and influential intellectuals of our time.

I am also incredibly grateful to have known Michael as my colleague, mentor, and friend. For three years, I had the good fortune to work with him at Ave Maria University, where I was a professor and where Michael, after his retirement from AEI, was a Distinguished Professor and Visiting Scholar. During those years, Michael and I would meet often for dinner or for drinks. Our discussion topics were wide-ranging: the Obama presidency and the past and future of the Republican Party; the historic Second Vatican Council, which Michael attended and wrote about; his campaigning and speech writing for Sargent Shriver in the 1970s; his wonderful friendships with John Paul II and Margaret Thatcher; his years as an ambassador during the Reagan administration; the history and current state of Catholic-Jewish relations. We also spoke of Michael’s own personal and intellectual journey from political liberalism to conservatism. At that time, he was writing about this journey in his insightful and compelling memoir, Writing from Left to Right, one of his last published books.

And, of course, we talked about baseball, which we both loved so much. He fondly recalled the many happy hours he had spent over the years with George Weigel and other friends at Baltimore Orioles games at Camden Yards. As a rabbi who has written about the history of Jews and baseball, I was delighted to tell Michael how proud I was that Camden Yards was the first baseball stadium in America to have a Kosher hot dog concession for religiously observant Jewish baseball fans. It is one of my abiding regrets that Michael and I didn’t have the opportunity to enjoy an Orioles game at Camden Yards together.

Above all, Michael was a truly wonderful and compassionate human being. In Yiddish phraseology, he was a true mensch. When I, although much younger than Michael, was going to undergo hip replacement surgery just a year after he had endured the same procedure, Michael spent much time advising and reassuring me about the upcoming surgery and the importance of physical therapy to my recuperation. For many months after my surgery, he would call me on a regular basis to ask how I was doing and to give me moral support. Michael had a wonderful capacity for empathy and friendship, the memory of which his many friends and admirers will always cherish.

In the words of the Jewish religious tradition, as I mourn the death of my friend, Michael Novak, my prayer is that his memory will always be for a blessing.