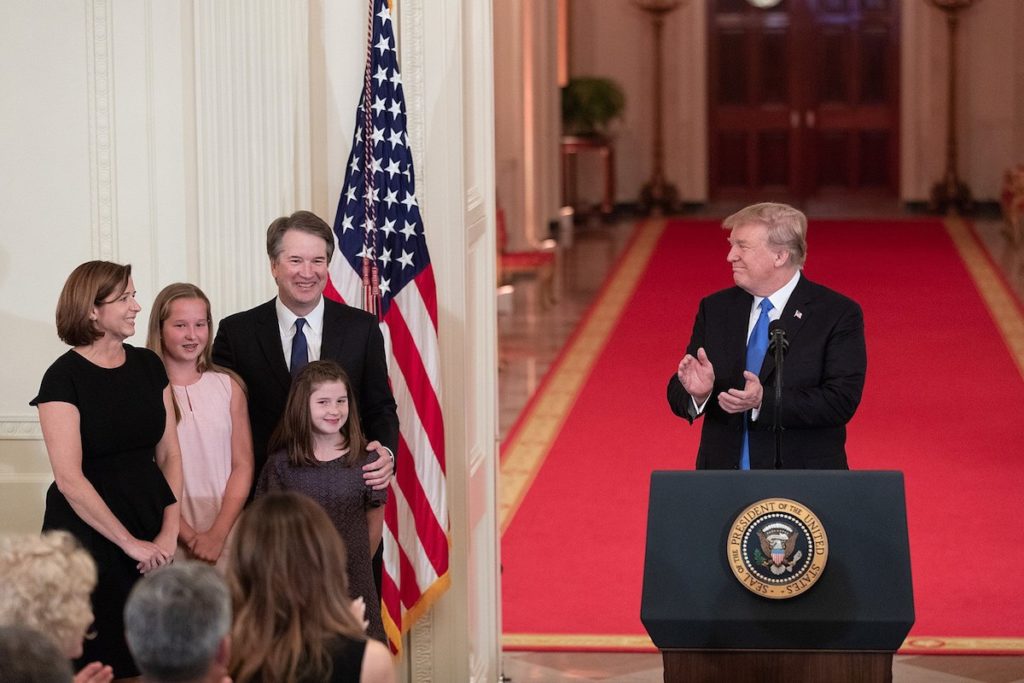

With President Trump’s nomination of Brett Kavanaugh to the US Supreme Court, observers of the federal judiciary are suddenly interested in the Roman Catholic faith. Many news reporters and opinion columnists breathlessly express anxiety about the religious commitments of federal judicial nominees, especially Christians who attend mass. A story about Brett Kavanaugh worries that he “could be instrumental in pitching the ideological makeup of the court to the right and leaving a conservative imprint on the law for a generation.”

A recent story about Leonard Leo, who advises the President on judicial nominees and is connected to the ascent of judges such as Kavanaugh, was even more hysterical. The author worried about a “secretive network of extremely conservative Catholic activists” who are stacking the federal courts with conservative jurists. Leo’s membership in the Knights of Malta, his public work in defense of religious freedom around the world, and his connection to Catholic-educated nominees such as Kavanaugh and Neil Gorsuch, all caused the author to fret that Leo is “shaping the federal judiciary according to his beliefs, with very clear ideological consequences.” The article asserts that the conviction that human life begins at conception is a religious belief. And it laughably attributes to Catholics the view that natural law “trumps any secular law that humans (or legislatures) might dream up.” Evidently, anti-Catholic hysteria trumps any research that journalists might dream up.

Other journalists have shown more knowledge and better judgment. They observe that Christian education forms character and makes men and women like Kavanaugh service-oriented and attuned to the needs of the poor. And they seem aware that Roman Catholics can read and apply the law.

Some Senators have injected nominees’ religious commitments into confirmation hearings. Senator Durbin made religion an issue during confirmation proceedings for another Roman Catholic judge, Amy Barrett. Senator Feinstein infamously raised the bar, telling then-Professor Barrett that the “dogma lives loudly within” her.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.All this raises the question whether Judge Kavanaugh’s religion should be an issue during his confirmation proceedings. It should. But not for the reasons that seem to interest Senators Durbin and Feinstein and reporters inside the Beltway.

Christianity and the Rule of Law

The American tradition of constitutionalism abhors inquiries into the particular creeds espoused by candidates and nominees for public office. The Constitution of the United States prohibits religious tests. And anyway, religion is not the issue. Fidelity to the rule of law is what matters. Anyone can determine to follow the law, even Senators Feinstein and Durbin.

There is no reason to think that someone who accepts on faith the teachings of the Bible or the Roman Catholic Church is any less capable of correctly interpreting and applying the law than someone who accepts on faith what scientists tell us about global warming. Faith in something must precede reason—at the very least, faith in reason itself—else we could never know anything.

Indeed, we all have dogmas living inside of us. Sometimes those dogmas conflict with the law. But they need not always, and the law itself is a moral reason. The job of the judge is to interpret and apply the law, whether the judge is a Christian or something else.

So, in terms of competence and fidelity to law, it is neither here nor there that a nominee to the Supreme Court of the United States is a Christian. But it is also important that the nominee understand the law. In this respect, Christians have an advantage. For Christianity shaped the conceptual and historical foundations of the rule of law, and Christians have carried it forward for centuries.

It is true that primordial elements of the rule of law precede Christian society. Hammurabi’s Code, the Ten Commandments, and the philosophy of Plato, Aristotle, and Cicero all supplied essential elements from which Christian societies crafted the rule of law. But it was Christians who did much of the crafting, both conceptually and historically.

Conceptually, to have the rule of law, a society must understand its officials and members to be obligated by rights and duties. The law must rule, not the desires and whims of individuals or classes. People must honor their duties toward others. We must do to others what is right according to law. Judicial officials must sanction and remedy wrongs when people infringe others’ rights. Also, law cannot simply be whatever the person says it is who has the most power. Law must be knowable to reason and binding on the weak and powerful alike.

Where the law rules rather than the powerful, law is accessible to reason, and the edicts and judgments of officials can be justified and critiqued on rational grounds. Those grounds were cleared by pagan philosophers. Plato’s philosophical precision, Aristotle’s distinction between natural justice and legal justice, and Cicero’s identification of right reason as natural law all made it possible to critique law on grounds of reason accessible to all. But Christians laid the foundation and built the edifice.

The Historical Christian Development of Common Law Jurisprudence

In early centuries, it was the Christian Saint Paul who taught that Christians have a duty in conscience to obey the law. Paul also taught the inherent dignity of slaves and women, that God created them as moral agents and loves them. It was the Christian Saint Augustine who articulated the natural law maxim that an unjust law is defective, unlawful. It was the Christian emperor Justinian whose jurists compiled the most important legal treatises in western jurisprudence, the Corpus Juris Civilis, synthesizing the legal achievements of the Roman Empire, the philosophical insights of the Greeks, and the Christian insistence that both citizens and rulers are obligated as a matter of conscience to obey the law.

In later centuries, it was the Christian theologian Thomas Aquinas whose Treatise on Law supplied the materials from which Continental, English, and American jurists drew their claims about natural law and natural rights and about the moral obligation to obey human-made law. It was the Christian jurists Edward Coke and Matthew Hale who incorporated those older ideas into a new, liberal common law jurisprudence. That common law jurisprudence made possible not only government under law but also rational justifications for the abolition of slavery and the civil rights movement.

Of course, it was Christ himself who instructed the conscientious to render to God what is God’s and to Caesar what is Caesar’s.

So, it was no coincidence that Martin Luther King Jr. expressly cited Hebrew and Christian scriptures, Augustine, and Aquinas when making his case that racial segregation is not only offensive but also unlawful, and that he made that case after willingly going to jail. The monumental American jurist Joseph Story did not exaggerate when he expressed the great boast that the rights and duties of Christianity are at the heart of our laws. Indeed, this is one sense in which we were founded as a Christian nation. Though our political institutions are designed to be secular and non-sectarian, our laws rest on Christian ideas about what we owe each other as human beings made in the image and likeness of God.

Those ideas needed to be put into practice before we could have anything like the rule of law. And though Christians have often violated the rights of others and disregarded their own duties, killing and enslaving and stealing, Christians also ended slavery, rebelled against tyranny, built institutions of legal justice, enforced the law, and launched the Civil Rights movement.

It was the Christian jurist William Blackstone who restated and organized the common law jurisprudence of Coke and Hale and transmitted it to the American colonies on the eve of the American revolution. Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England, the most influential treatise in American jurisprudence, begins with an extended discourse on the relation between God and His human creatures and on the superiority of divine and natural law over human law, natural law that itself supplies the authority of human law. Notably, Blackstone summarized the natural-law case against slavery and racial injustice and explained why the common law could support neither. The great American emancipator, Abraham Lincoln, said that the Commentaries formed his understanding of law and its relationship to justice and motivated him to pursue a career as a lawyer.

Magna Carta, the English Bill of Rights, and the Declaration of Independence together teach that government officials serve the law, not the other way around, because God gives the law as an inheritance to all His human creatures. Those documents vindicated ideas articulated by Christian philosophers and jurists. And many Christians have given their lives to ensure that the rule of law would protect more Americans, without regard to race or creed.

Senators who simultaneously express concern for the rule of law and anxiety about a Christian on the Supreme Court demonstrate an alarming combination of ignorance and ingratitude. Perhaps we should not be surprised. Many Senators were educated at elite law schools, and most law schools ignore the foundations of law. Notre Dame (where Judge Barrett and I both studied) and Faulkner Law (where I teach) are among the few to teach all students about the ideas and human actions that have made the rule of law possible. Though Judge Kavanaugh graduated from Yale Law School, he nevertheless has the advantage of being a Christian who is catechized in the tradition that resulted in the rule of law in the United States. Perhaps he can teach Senators Feinstein and Durbin how to quiet their own dogmas and follow the law.