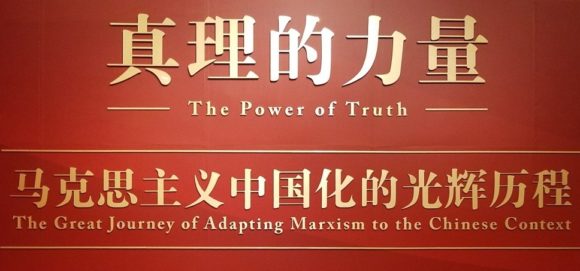

Over the past several years I have visited more than a dozen Chinese universities, speaking on “Thomas Aquinas, Creation, and Contemporary Science.” One of my goals has been to show how Aquinas’s philosophy of creation is not challenged by recent developments in evolutionary biology and cosmology. In 2018 I visited Beijing’s National Museum of China, where there was a special exhibition, “The Power of Truth,” celebrating the two hundredth anniversary of the birth of Karl Marx. The first sentence of the introduction described Marx as “a thinker and revolutionist whose influence has been the most far-reaching in the history of world civilization.”

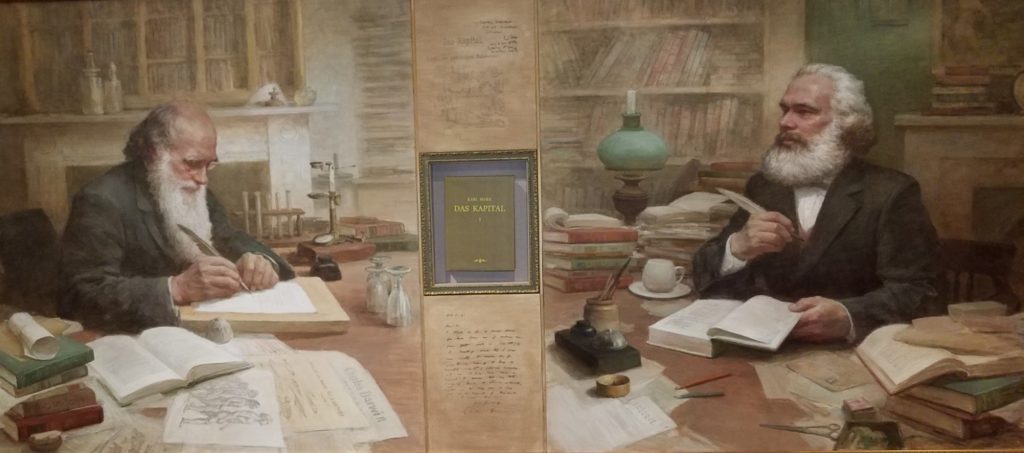

One hall was dedicated to the life and works of Marx, especially the Communist Manifesto; another section, “The Great Journey of Adapting Marxism to the Chinese Context,” emphasized the thought of President Xi Jinping; and a third contained monumental paintings with Marx as the focus. I was intrigued by a picture of a famous story about Karl Marx and Charles Darwin.

Darwin and Marx in England

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Giving Das Kapital to Darwin, by Qin Wenqing (2018)

This painting commemorates an event in 1873 when, after the publication of Das Kapital, Marx, who was living in England at the time, sent an inscribed copy of the second German edition to Darwin. Darwin responded:

I thank you for the honour which you have done me by sending me your great work on Capital; & I heartily wish that I was more worthy to receive it, by understanding more of the deep & important subject of political Economy. Though our studies have been so different, I believe that we both Earnestly desire the extension of Knowledge, & that this in the long run is sure to add to the happiness of Mankind.

The central column in the painting depicts Marx’s inscription in the book, the cover of Das Kapital, and Darwin’s letter to Marx.

Marx and Darwin are icons of modernity, especially of a secularist and materialist view of reality. Both have been used to reach the conclusion that the doctrine of creation is an artifact of a less enlightened age. Challenging such a conclusion has been the theme of my lectures in China, and elsewhere.

Marx and Darwin are icons of modernity, especially of a secularist and materialist view of reality. Both have been used to reach the conclusion that the doctrine of creation is an artifact of a less enlightened age. Challenging such a conclusion has been the theme of my lectures in China, and elsewhere.

Marx and the Denial of Creation

Being committed to materialism and the rejection of transcendence, Marx claimed that “Once the beyond of truth has vanished, it is the task of history to establish the truth of the here and now.” Only with the abolition of the illusory salvation of religion can one achieve earthly happiness.

After the publication of On the Origin of Species in 1859, Friedrich Engels called Marx’s attention to Darwin’s work. At Marx’s funeral Engels remarked: “Just as Darwin discovered the law of development of organic nature, so Marx discovered the law of development of human history.” Marx himself had written to Engels that The Origin “contains the basis in natural history for our view.” In another letter he says that the theory of natural selection serves as a foundation “in natural science for the class struggle.” In 1880, Engels published an excerpt from his Anti-Dühring, under the title, Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, in which he observed:

Nature is the proof of dialectics, and it must be said for modern science that it has furnished this proof with very rich materials increasing daily, and thus has shown that, in the last resort, Nature works dialectically and not metaphysically; that she does not move in the eternal oneness of a perpetually recurring circle, but goes through a real historical evolution. In this connection Darwin must be named before all others. He dealt the metaphysical conception of Nature the heaviest blow by his proof that all organic beings, plants, animals, and man himself, are the products of a process of evolution going on through millions of years.

Darwin in China

In 2019 I was again in China and visited an exhibition in the Shanghai Library that celebrated the 160th anniversary of the publication of On the Origin of Species. Part of the exhibit concerned the interest in Darwin in late-nineteenth-century China, especially after China’s defeat in the Sino-Japanese War. The defeat encouraged Chinese scholars to pay greater attention to the benefits of Western science and technology.

Yan Fu (1854–1921) was among the first Chinese to be educated in Great Britain. He introduced the principal ideas of Darwinian evolution to Chinese audiences in 1898 with his translation of Thomas Huxley’s essay Evolution and Ethics as Tianyan lun (The Theory of Evolution) and in 1903 with his translation of Herbert Spencer’s The Study of Sociology (Qunxue yiyan). In the former, Yan Fu noted that Darwinism has shown that there is no “so-called creator.” A translation of all of Darwin’s Origin was completed by Ma Junwu (1881–1940) in 1919.

The introductory placard to the exhibit noted: “For the next several decades the theory of evolution influenced the May 4th Movement (1919) and the New Cultural Movement (1915–1921), provided ideological weapons to reformers, republicans, anarchists, and revolutionaries, and, eventually, formed a social evolutionism that met Chinese national conditions.” James Pusey, writing in China and Charles Darwin (1983), summarized the Darwinian arguments used against the rule of the Dowager Empress: “You and your race are unfit. You will perish through natural selection. Evolution will sweep you aside.”

An important individual in the Reform Movement was Lu Xun (1881–1936). In his early years, he too read Huxley’s Evolution and Ethics and then, later, Ernst Haeckel’s The Riddle of the Universe (1895–99). Lu appropriated important parts of the chapter titled “The History of Our Species” in Haeckel’s book in his own “The History of Mankind,” (Ren zhi lishi) published in 1907.

Lu embraced Haeckel’s analysis of what he considered the philosophical and theological implications of Darwinian thought. In a characteristic passage, Haeckel wrote that “[e]very serious attempt that was made before the beginning of the nineteenth century to solve the problem of the origin of species lost its way in the mythological labyrinth of the supernatural stories of creation.” According to Haeckel, Darwin had demolished the “prevailing Doctrine of Design, or Teleology”: since was there no designer, obviously there was no creator. The popes, ultimate defenders of “the Doctrine of Design, . . . were the greatest charlatans in world history.” Haeckel concluded that “[t]he theory of evolution was established upon the refutation of the theory of divine creation” and ridiculed “the Western notion of a personal creator acting for a definite purpose.” Haeckel often pointed to the “natural and inevitable . . . vehemence of opposition between science and Christianity.”

Hu Shih (1891-1962), one of the leaders of the literary reform movement in the 1930s, observed in his autobiography (Ssu-shih tzu-shu): “Not many years after the translation of Evolution and Ethics, it became highly popular throughout the country and became the favorite reading of secondary school students. After China’s frequent military reverses, particularly after the humiliation of the Boxer years, the slogans of ‘Survival of the Fittest’ became a kind of clarion call.”

With the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (1949) and the embrace of Marxism as the dominant intellectual and cultural construct, in China Darwinism came to be seen as supporting a Marxist and materialist understanding of reality. This view was evident at the “Meeting in Commemoration of Great Figures in World Culture,” organized in Beijing on May 27, 1959. It was the one hundredth anniversary of the publication of Darwin’s Origin and the tenth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic. Two scientists spoke about Darwin: Bing Zhi, president of the Zoological Society of China, and Zheng Zuoxin, secretary-general of the same society. Bing noted that Darwin’s work “sets forth a new outlook on the universe, which overthrows the superstitious allegation that God is the creator . . . and was therefore greatly opposed by the religious circles as well as the idealists [who deny materialism].” Zheng thought that Darwin’s commitment to an exclusively materialist understanding of reality and his rejection of any form of teleology in the natural order were especially important:

As everybody knows, in Europe since the fourth century, religion had a grip on people’s thoughts. All plants and animals were then regarded as being created by God and thus remaining immutable. Since all creatures were specially created, they were undoubtedly created to serve special purposes. This sort of metaphysical viewpoint, related to a low scientific level as it is, serves particularly the purpose of the reactionary ruling class, who were eager to maintain the status quo. Overthrowing these metaphysical allegations, Darwinism ended the reign of [an] idealistic outlook in the people’s way of thinking, and set up historical and materialistic viewpoints in the biological domain. Only on the basis of Darwinism has biology been able to develop as a modern science and to attain such achievements as it has today.

In this analysis, Darwinism prepares the way—at least in a logical sense—for a broader Marxian understanding of the materialistic basis of all of history. We might even say: After Darwin, Marx.

Evolution and the Metaphysics of Creation: The Insights of Thomas Aquinas

The fascination with Darwin, and the use of him to support a Marxist view of reality, ought not to be surprising. The connection between Darwinian biology and the denial of the doctrine of creation, the elimination of purpose in nature, and the acceptance of a materialistic conception of reality, are evident in many Western interpretations of Darwin’s thought.

Thomas Aquinas offers a powerful antidote to the confusion between developments in the natural sciences and in metaphysics, the science of being as being. For Aquinas, metaphysics transcends (but does not contradict) natural science. Even without the aid of revelation and theology, metaphysics can demonstrate that there is a Creator. Marxist materialism is a comprehensive philosophical claim and is incompatible with Thomistic philosophy; Darwinian evolution, on the other hand, is one of the natural sciences and ought not to be conflated with any metaphysical doctrine, least of all materialism.

The natural sciences have as their subject the world of changing things: from subatomic particles to acorns to galaxies. Whenever there is a change there must be something that changes. Creation, on the other hand, is the radical causing of the whole existence of whatever exists.

The natural sciences have as their subject the world of changing things: from subatomic particles to acorns to galaxies. Whenever there is a change there must be something that changes. Creation, on the other hand, is the radical causing of the whole existence of whatever exists. To cause completely something to exist is not to produce a change in something; it is not to work on, or with, some existing material. If, in producing something new, an agent were to use something already existing, the agent would not be the complete cause of the new thing. But such complete causing is precisely what creation is. To create is to cause existence itself, and all things are totally dependent on the Creator for the very fact that they are.

It is an error to think that God’s causal agency differs only in degree from the causes that operate in the natural order. Therefore it is also erroneous to think that the more we attribute causal power to the world, the less we attribute to God, or vice versa.

Evolutionary biology and all the other natural sciences offer explanations of what we might consider a horizontal or linear dimension of reality—of all the changes, large and small, that occur over the course of history, however extended that history may be. Creation concerns, if you will, a vertical dimension that is constantly present throughout the entire sweep of change. Without that vertical dimension, from which existence as such comes, there would be no horizontal dimension at all. Even this image falls short of what it means for God to be the transcendent cause of existence.

What often intrigues my Chinese colleagues and students is that we do not need to accept the Christian faith that Aquinas embraced to see that, on his philosophical principles, there is no need to choose between viewing creation as the constant exercise of divine omnipotence and acknowledging the causes that the natural sciences disclose. God’s creative power is exercised throughout the entire course of cosmic history, in whatever ways that history has unfolded. No matter how random one may think evolutionary change is, no matter how much one may think that natural selection is the master mechanism of change in the world of living things, the role of God as Creator, as continuing cause of the whole reality of all that is, is not challenged.

We need to remember Aquinas’s fundamental point that creation is not a change, and thus there is no possible conflict between the natural sciences—whose domain is the world of change—and the truth of creation. Even if one embraced an exhaustive materialist account of reality, evolutionary biology itself does not require such an affirmation.