Friedreich Nietzsche shows us that the real, intellectually consistent alternative to the Christian view of ethics and anthropology is not warm and comfortable secular liberalism, but something much more terrible and dangerous. In his essay “The Greek State,” Nietzsche writes: “Such phantoms as the dignity of man, the dignity of labor, are the needy products of slavedom hiding from itself. . . . ‘Man in himself,’ the absolute man possesses neither dignity, nor rights, nor duties.” Last summer, a few days before my son was born, The Philosophers Magazine tweeted a similar if less dramatically phrased quotation from the Australian philosopher Peter Singer: “The notion that human life is sacred just because it is human life is medieval.” This is correct—albeit a poor use of the adjective medieval to mean archaic, backward, and obviously wrong to enlightened people. But Singer could have been more historically precise had he said, “The notion that human life is sacred just because it is human life is patristic.”

This is effectively Nietzsche’s point as well: the concept of human dignity is a relic of Christianity, a fragment of that revolt of slave morality that toppled pagan religion and dramatically changed our view of humanity. Nietzsche and Singer are right: Christianity introduced for the first time the idea of human dignity, which I define as the idea that all human beings are in some way special or worthy of respect simply because they are human beings and irrespective of their particular merits or abilities. Human dignity comes out of the teachings of Jesus and the encounter between Christians and the pagan world.

Of course, the concept of human dignity develops extensively in Kant and Enlightenment philosophy, and human dignity as we most fully understand the concept today was not present in the patristic era. But it behooves us to examine some of the important early Christian texts about human dignity, especially as interpreted by the classicist Kyle Harper and the New Testament scholar C. Kavin Rowe, before considering lessons for living in a time that many describe as being newly pagan or post-Christian. If human dignity is a Christian concept, what happens to it after Christianity?

Christianity and the Classical World

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.That question gains an edge when we remember that, as Harper has noted, “none of the classical political regimes, nor any of the classical philosophical schools, regarded human beings as universally free and incomparably worthy creatures. Classical civilization, in short, lacked the concept of human dignity.” Aristotle famously believed that some human beings were destined to slavery by nature and lacked the moral reason necessary for flourishing as free agents. Some have pointed to Cicero’s De officiis, where he writes that “if we consider what dignitas and excellence there is in nature, we will realize that it is disgraceful to revel in luxury and to live a soft and dissolute life.” But, Harper argues, this is more a statement of moral egalitarianism that all human beings have reason and therefore moral personhood than an imputation of dignitas or worthiness to every human being. It is an exhortation to live a moral life, not a statement that all human lives have equal inherent worth.

Christianity’s teaching about human nature emerged in the classical world without precedent. As Rowe puts it, it was one of the “surprises” that this new movement brought into the world. This teaching grew out of the Jewish understanding that the Jewish people reflected the God of Israel and the life he desired for and with human beings. The New Testament revealed that it is the person of Jesus of Nazareth himself who is the Imago Dei, in two senses. Jesus is called “Lord,” just as God is, and the Son of God, the refulgence of the Father’s glory visible to us. He is also the New Adam, the one who in his person shows us what it truly means to be human.

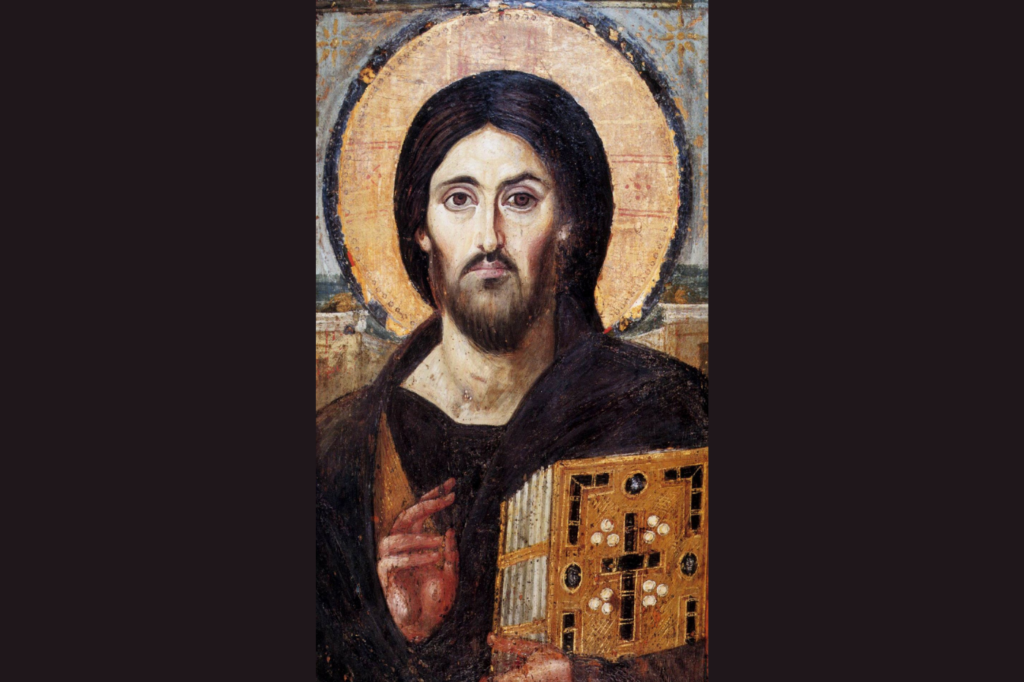

The early Christians and the New Testament took the logic one step further: If Christ reveals what it means to be human being, then when you encounter another human being, no matter his status or background or creed, you are encountering Christ. We see this in Jesus’s words about the judgment of the nations in Matthew 25, which we tend to hear as an exhortation to love Christ through the corporal works of mercy: “Whenever you did it to one of the least of these, you did it to me.” Rowe notes, however, that the parable turns on a contradiction. The Son of Man comes to judge the world as a king, and we know that kings are majestic, not lowly. The image of a king in majesty is one that is seen throughout the kingdom, on its coinage and in public proclamations and monuments. In an important sense, you treat the image as you would the king, with reverence and respect. Yet this king, Jesus, says that the poor and destitute are representations of him. When you see them, you see the king and should treat them as one would treat him. In other words, all people have dignity because they are made in the image of God, which is the image of the crucified and risen Lord Jesus. The Christian roots of human dignity are therefore both broad and Christological. In Rowe’s words, “because Jesus Christ is the human, every human is Jesus Christ.”

As this understanding of human dignity encountered the pagan world, it called for radical reforms of familiar social institutions and the creation of new and unprecedented ones. Harper argues that three of the most important points of encounter were slavery, sexual coercion, and care for the poor and the sick.

If Christ reveals what it means to be human being, then when you encounter another human being, no matter his status or background or creed, you are encountering Christ.

Slavery and the Church

In our society, slavery enjoys almost universal condemnation and is seen by both right and left as America’s original sin. But we are a rare exception. Most societies in human history have accepted slavery in some form or other. In the world of the early Christians, slavery was pervasive and morally acceptable. And for the most part, Christians were quite willing to live with it.

Then, in the fourth century, Gregory of Nyssa preached a homily that stands as the first recorded opposition to slavery as an institution anywhere in the world. Gregory was preaching on Ecclesiastes 2, where Qoheleth reflects on the futility of his pursuit of pleasure and riches. In Ecclesiastes 2:7, he writes, “I bought male and female slaves, and had slaves who were born in my house; I had also great possessions of herds and flocks, more than any who had been before me in Jerusalem.” Gregory sees this as the crescendo of Qoheleth’s confession of pride, and his words are worth quoting at length:

You condemn man to slavery, when his nature is free and possesses free will, and you legislate in competition with God, overturning his law for the human species. The one made on the specific terms that he should be the owner of the earth, and appointed to government by the Creator—him you bring under the yoke of slavery, as though defying and fighting against the divine decree. . . .

What did you find in existence worth as much as this human nature? What price did you put on rationality? How many obols did you reckon the equivalent of the likeness of God? How many staters did you get for selling the being shaped by God? God said, let us make man in our own image and likeness (Gen. 1:26). If he is in the likeness of God, and rules the whole earth, and has been granted authority over everything on earth from God, who is his buyer, tell me? who is his seller? To God alone belongs this power; or rather, not even to God himself. For his gracious gifts, it says, are irrevocable (Rom. 11:29). God would not therefore reduce the human race to slavery, since he himself, when we had been enslaved to sin, spontaneously recalled us to freedom. But if God does not enslave what is free, who is he that sets his own power above God’s?

How too shall the ruler of the whole earth and all earthly things be put up for sale? For the property of the person sold is bound to be sold with him, too. So how much do we think the whole earth is worth? And how much all the things on the earth (Gen. 1:26)? If they are priceless, what price is the one above them worth, tell me? Though you were to say the whole world, even so you have not found the price he is worth (Matt. 16:26; Mk. 8:36). He who knew the nature of mankind rightly said that the whole world was not worth giving in exchange for a human soul. Whenever a human being is for sale, therefore, nothing less than the owner of the earth is led into the sale-room.

For Gregory, there are three interrelated problems with slavery. First, it is a kind of prideful idolatry in which a human being tries to take the place of God as the one who owns another human being, when God has created man and declared him free. Second, God gave man a free nature and free will and appointed him lord over creation; to take such a man and in turn subject him to yourself as though he were an animal is to subvert the law of God. Third, God made man in his image and likeness and therefore man would exceed any price that could be offered for him. When a human being is offered for sale, it is as if God himself were on the auction block.

Gregory’s words did not provoke a revolution overnight, but they give an intimation of how the logic of human dignity in the Christian message would one day overthrow a human institution that seemed inevitable, if not natural.

Sexual Coercion and Christian Morality

Just as Greeks and Romans had no problem with slavery, they likewise had no problem with sexual coercion—at least for some people. Ancient sexual norms were organized around reproduction and involved flagrantly double standards. Harper writes: “For free, respectable women, whose bodies were conscripted to the duties of legitimate reproduction, sexual honor strictly required virginity until marriage and chastity within married life. For men, premarital sex was unproblematic, frankly expected; extramarital sex was widely tolerated.” Since girls married in their teens and men in their twenties, “the outlet of male sexual energy, therefore, was the exploitation of bodies not policed by expectations of social honor.” “Sexual coercion was an ordinary part of the slave’s experience,” and prostitution was legal and widespread for those who could not afford slaves.

Early Christian sexual morality therefore offered a sharp contrast with the pagan world; it was another of the new religion’s “surprises.” Paul exhorted men to remain faithful to their wives and to shun prostitution. Once the Church became more established after the conversion of Constantine, the logic of its view of sex and human nature conflicted with the systematic sexual exploitation of those who lacked social honor. In a sermon on Psalm 32 pondering the mysteries of God’s providence, Gregory of Nyssa’s brother Basil the Great of Caesarea writes: “For while the slave woman who was sold to a pimp is in sin by necessity, she who happens to belong to a wellborn mistress was raised with sexual modesty, and on this account the one is shown mercy, the other condemned.” In other words, women who were sexually coerced could not be held responsible for acts that went against their will.

Once the Church became more established after the conversion of Constantine, the logic of its view of sex and human nature conflicted with the systematic sexual exploitation of those who lacked social honor.

Unlike Gregory’s writing on slavery, this line of logic did have direct political consequences. In 428, the Byzantine emperor Theodosius II issued a startling decree:

We cannot suffer for pimps, fathers, and slave-owners who impose the necessity of sinning on their daughters or slave women to enjoy the right of power over them nor to indulge freely in such crime. Thus it pleases us that these men are subjected to such disdain that they may not be able to benefit from the right of power nor may anything be thus acquired by them. It is to be granted to the slaves and daughters and others who have hired themselves out on account of their poverty (whose humble lot has damned them), should they so will, to be relieved of every necessity of this misery by appealing to the succor of bishops, judges, or even defensors. So that, if the pimps shall think these women are to be urged on or impose the necessity of sin on those who are unwilling, they will lose not only that power which they held, but they will be proscribed by exile to the public mines, which is less of a punishment than that of a woman who is seized by a pimp and compelled to endure the filth of an intercourse that she did not will.

This is a direct translation of the Christian understanding of human dignity and sexual morality into law, and brought new ideas like Basil’s “necessity of sinning” into the Roman legal system. “For the first time,” Harper writes, “the bodies of those without any familial or civic claim to sexual honor received the protection of the state, simply by virtue of their human dignity.” Subsequent emperors expanded this ban, culminating with the Emperor Justinian’s creation of a special task force to investigate coercion in the sex industry in Constantinople and his creation, along with his wife Theodora, of a convent for reformed prostitutes.

Care for the Poor and Sick

A third point of encounter between the Christian understanding of human dignity and the ancient world came in the care for the poor and the sick. Care for the poor has been a staple of Christian ethics from the parables of Jesus onward. This was yet another “surprise” that Christianity introduced to the world, for the Roman world had no concept of “the poor” as a group of people who deserved care simply because they were indigent human beings. Many aspects of civic life in the Greco-Roman world were sponsored by wealthy patrons, but the goal was to enrich the lives of citizens of a city or one’s personal clients. You took care of those with whom you had a civic or familial bond because of that bond, not simply because they were in need. But Christians were deeply concerned that people made in the image of God should suffer want and disease without relief. They invented shelters for the poor and hospitals, institutions that had not existed prior to this time.

Each of the three great Cappadocian Fathers preached or acted on behalf of the poor and the sick. Basil the Great built a major hospital outside Caesarea known as the Basileias, which cared for the poor, homeless, orphans, and lepers in different sections. Patients could receive trained medical care as well as shelter and nourishment, at no cost and for as long as their treatment required. The church and the local government supported the institution, the latter mostly by tax exemption.

Christians should care for these people not because they were family or even fellow Christians, but because they bore the πρόσωπον (prosopon), the image or mask, of Jesus.

In his oration on the love of the poor, Gregory of Nazianzus urges his listeners to remember that God created human beings free and with free will, and that poverty was an evil of fallen humanity, not a part of original creation. He speaks of the equal dignity of those tormented by exposure to the elements: “This is how they suffer, and in fact far more wretchedly than I have indicated, these, our brothers in God, whether you like it or not; whose share in nature is the same as ours; who are formed of the same clay from the time of our first creation . . . more importantly, who have the same portion of the image of God just as we do and who keep it perhaps better, wasted though their bodies may be.”

And Gregory of Nyssa argues that poverty does serious injury to the dignity that every human being bears by being made in the image of God: “Do not have contempt for those who lie prostrate as if they were of no worth. Learn who they are and you will discover their dignity (τὸ ἀξίωμα). They have put on the personhood (τὸ πρόσωπον) of our savior. The one who loves humanity gave to them his own person to forestall those who lack sympathy or hate the poor, like those who display the images of the emperors against those would use violence, so that their contempt is forestalled by the image of power.” Christians should care for these people not because they were family or even fellow Christians, but because they bore the πρόσωπον (prosopon), the image or mask, of Jesus. They were made in the image of the God the Christians claimed to serve—a God who commanded them to love all those created in his image, who revealed that image in the Savior Jesus.

Human Dignity in a Post-Christian World

As we have seen repeatedly, the vision of human dignity present in these patristic texts was a new idea that Christianity brought to the ancient world. This pattern persisted throughout history into the twentieth century: when Christianity enters a society, it provides an understanding of inherent and equal human dignity that lifts up those whom that society has considered unworthy. For example, in 1930–31 the Methodist bishop of India J. Waskom Pickett conducted a rigorous study of the conversions of thousands of members of the untouchable or Dalit caste to Christianity as a result of English evangelization. In most cases, Rebecca Shah writes, “the motive [for conversion] lay in the Dalit belief that Christianity embodied a life of dignity and hope for a future free of degradation and subservience.” As one convert put it, “I wanted to become a Christian so I could be a man. None of us was a man. We were dogs. Only Jesus could make men out of us.”

If this is what happens when Christianity advances in a society, what happens when Christianity recedes? Can you have moral principles like human dignity without the Christianity that brought them into being? Perhaps for a while. Eventually, however, they will become disconnected from the framework in which they arose. Christian human dignity is not founded on maximizing fairness or autonomy, but on the fact that all human beings are made free and in the image of God. If it becomes detached from that principle, then human dignity will no longer make sense in its original form. It will grow differently when grafted onto a new religious or philosophical branch. The temptation to make exceptions to gratify the will of the strong will prove irresistible.

C. S. Lewis and Alasdair MacIntyre arrived at similar conclusions about moral reasoning in the twentieth century. In The Abolition of Man, Lewis argues that stepping outside a moral system obedient to the principles of morality inherent in the human condition, which he called the Tao, will lead not to man’s ultimate conquest of his own nature, or the triumph of rational morality over superstition and tradition, but to the domination of the weaker by a minority of the strong: “what we call Man’s power over nature turns out to be a power exercised by some men over other men with Nature as its instrument. . . . Stepping outside the Tao, they have stepped into the void. . . . Man’s final conquest has proved to be the abolition of Man.” Likewise, MacIntyre argues that the failure of the Enlightenment leaves us with a choice between the Aristotelian morality that the Enlightenment rejected or the Nietzschean argument that “if there is nothing to morality but expressions of will, my morality can only be what my will creates.”

Recall that human dignity’s historical roots lie in Christian theological principles—principles that, pace Lewis, are not broadly found in the religions of history and the Tao or in the natural reasoning of Aristotle. If this is so, and if Lewis and MacIntyre are right that a rejection of moral reasoning more broad and foundational than Christian revelation leads to the domination of the strong over the weak, then we have all the more reason to think that human dignity will lack purchase outside a Christian theological framework. To radically paraphrase Elizabeth Anscombe in her famous paper “Modern Moral Philosophy,” the ethical “oughts” of human dignity will not make sense without their theological foundations, and a consequentialism opposed to dignitarian moral claims will replace them.

A post-Christian society is not one in which we finally get the baggage out of the way so that human dignity can become more widespread, but a society in which the reasons for caring for the poor and the sick or protecting the sexually vulnerable make less sense to those with power and are therefore less widely practiced. We need Christianity if human dignity is to remain comprehensible and lived out. Only Jesus can make men and women out of all of us.

This essay was adapted from a paper presented at the University of Notre Dame’s de Nicola Center for Ethics and Culture Fall Conference in November 2021.